In February 2006, I landed at Changi Airport in Singapore on a two-day stopover en route to a vacation in Australia. It was Chinese New Year. In the evenings, fireworks popped overhead in the steamy summer heat.

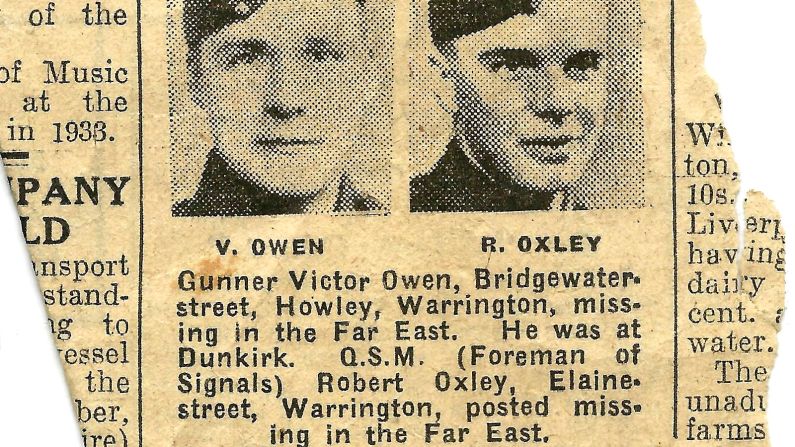

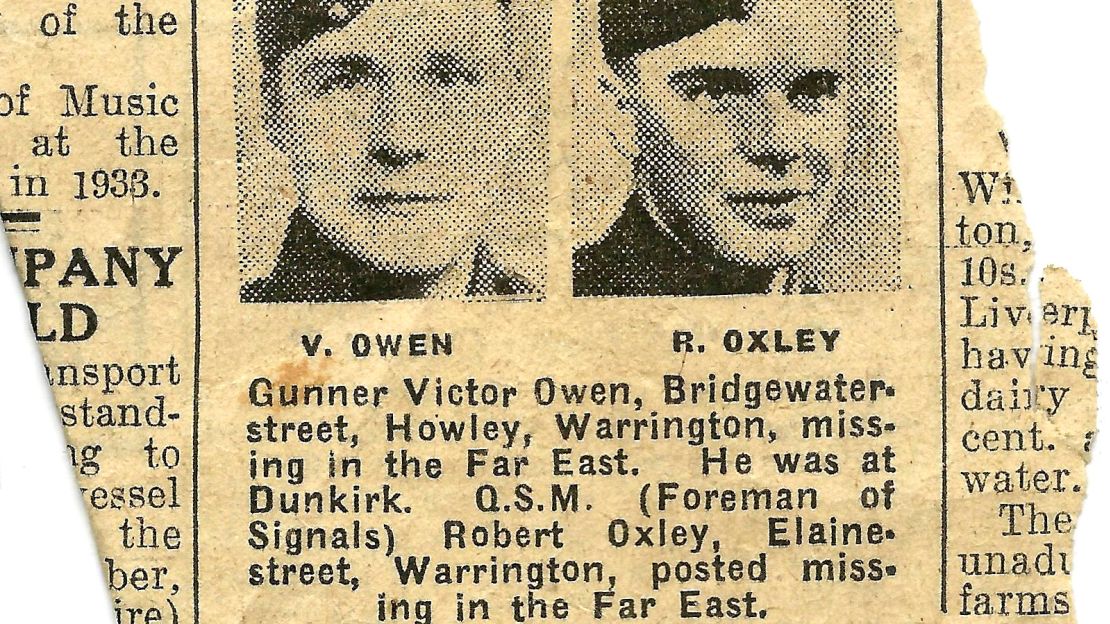

More than 60 years earlier my grandfather, Quartermaster Sergeant Robert Oxley, was also in Singapore. He had just arrived with the British Army’s 18th Infantry Division. He was Foreman of Signals and had sailed into a wartime disaster.

My grandfather’s military records meticulously note that he’d embarked in Liverpool, England. At some point the ship had a stopover in Bombay – now Mumbai – India, and he arrived in Singapore on January 15, 1942.

Exactly one month later, neat writing in his file lists my grandfather as: “Missing Malaya. Unconfirmed POW in Japanese hands.”

He wasn’t the only one.

Almost the entire British and Allied contingent in Singapore, a colony and strategic base for Pacific operations, had been taken prisoner of war. The fall of Singapore turned out to be one of British wartime leader Winston Churchill’s biggest strategic blunders of World War II. The British troops were surprised and overwhelmed by a much smaller Japanese force.

Mementos of war

Everyone called my grandfather Ro, a phonetic interpretation of his initials. He was 24 when he first arrived in the Asian theater. He wasn’t to leave for another three and half years.

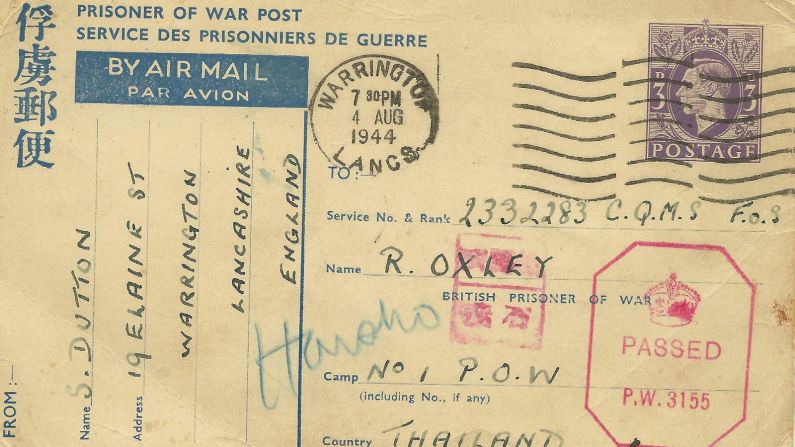

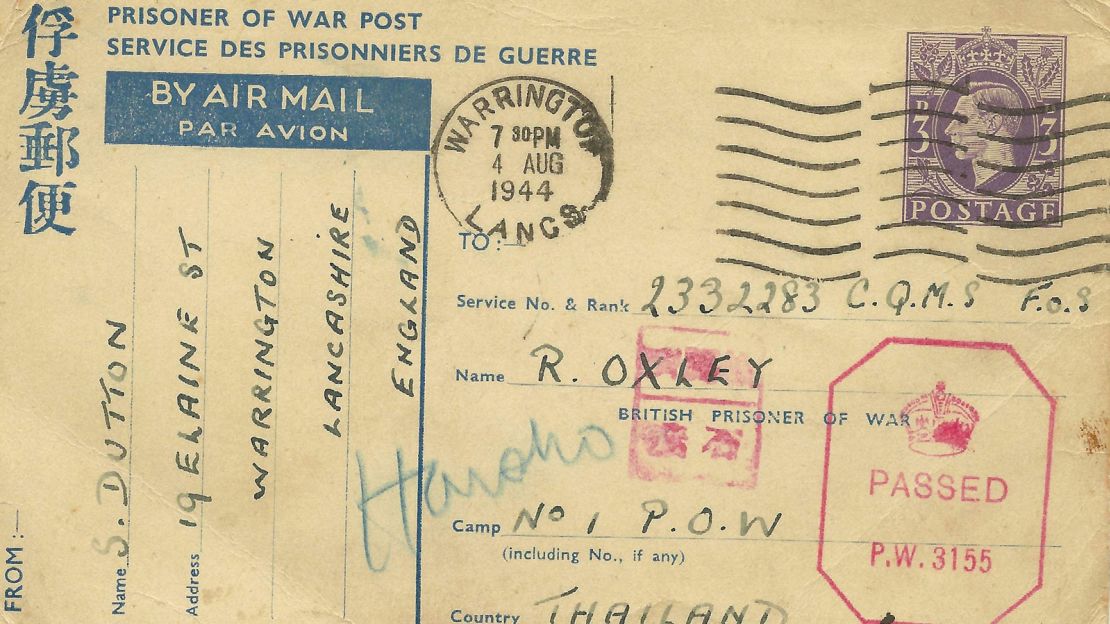

Our family hasn’t quite pieced together his movements during his years as a Japanese prisoner of war, but we have some indication where he was taken from a small pile of his wartime “memorabilia” that my grandmother has kept in a brown envelope for nearly 70 years.

There’s a sketch of him, a miniportrait, a profile etched in pencil on a scrap of paper, that’s survived the decades.

In the corner, half torn away, are the words “Changi, 1942” – not a reference to Singapore’s airport, but to a prison built there by the British that was used by the Japanese to house their captives.

During my trip, when I walked to the site of the old Changi Prison – slowly, because it was so hot – I wondered how my red-headed, pale-skinned grandfather from Warrington in northwestern England had dealt with the searing temperatures and burning sun of Southeast Asia.

The Allied soldiers were initially imprisoned in Changi jail, and then sent as forced labor to build the Burma-Siam railway.

It became known as the Death Railway because so many were brutalized and died during its construction. After the war, many Japanese were convicted of war crimes for the barbaric way they treated prisoners during its construction.

We don’t know where or when Ro worked on the railway, but we do know somewhere along the route he was in “POW camp No.1 Thailand” because we have card-like telegrams sent to him there, via the Red Cross, from his family back home.

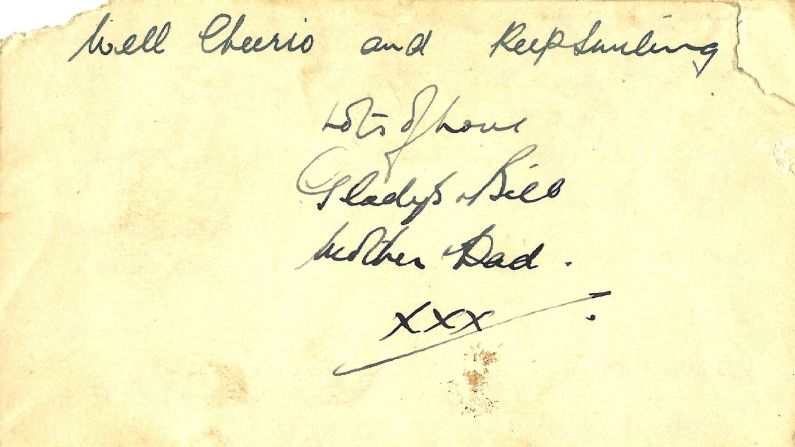

In one missive they sign off, “Well cheerio and keep smiling, from Bill, Gladys, Mother and Father.”

Messages to the dead

Today, the site of Changi Prison is a memorial, a museum of horrors laid out for sightseers, tourists and people like me: descendants of Allied prisoners who make the trip to find a connection, to glean some understanding of what those poor souls went through.

There’s a chapel-sized room of notes pinned up, layer upon layer, on boards attached to rough wooden walls. Messages to the dead, in different languages, many from the families of those who survived or those who didn’t.

I wrote a note too. I can’t remember what I said.

It’s strange being in a bad place that should resonate with you. I tried but couldn’t quite imagine what Ro and his fellow prisoners went through. Instead I just tried to digest what I already knew.

A prisoner of war brings that war home with him. Ro did. It haunted him.

I believe that he passed some, perhaps just a little bit, of that trauma to my mother, and she in turn – the child of a POW most likely suffering from some degree of post-traumatic stress disorder – parented my brothers and I with the vestiges of long-ago war seared into our family DNA.

Psychologists call it “transgenerational trauma,” and it’s been expertly documented in the children of Holocaust survivors. Children take on their parent’s experience in the most extreme cases. Or, as the offspring of many military veterans know, they just have to deal with a parent who can relive those foreign war experiences at home.

Imprisoned in a bamboo cage

My mother told me that as a child she rarely had sleepovers with friends because Ro would routinely have nightmares, screaming and yelling in his sleep.

She didn’t want her friends to be scared by what had become semi-routine in the household.

During these episodes, my grandmother remembers him jumping up on the bed, his arms flailing desperately above his head.

My grandmother thinks this was because Ro, like many other Japanese POWs, was kept in or imprisoned in a bamboo cage. Granny thinks, in his sleep, he was trying to stop snakes dropping on him through the gaps in his bamboo cage. Or maybe he was trying to stand up or escape the confines of the small enclosure?

I can’t verify the story. No one really asked him about it. In the morning, their lives went on as normal. This was a generation that soldiered on stoically.

Only after my trip to Singapore did I read the book “The Railway Man” by Eric Lomax. There’s now also a movie with Colin Firth playing Lomax, who like my grandfather was a Japanese POW.

Decades after the war, Lomax returns to Changi and the Burma Railroad to confront his Japanese guard. He also tries to come to terms with the torture he endured in bamboo cages. In the movie, the cages are lined up in a courtyard at Changi. I didn’t see them when I was there. I don’t think I needed to.

Acceptance and respect

So this trip changed my life because it brought perspective, a sense of understanding, acceptance and respect. Every family has their unique history, a timeline of happy and sad experiences that impact future generations, or don’t.

I spent just a few hours at Changi, only two days in Singapore, but I left knowing that if Ro survived nearly four years of brutality in Changi Prison and as a slave laborer on the Burma Railroad then, frankly, I could and should be able to deal with just about anything.

He went on to have a career and a family.

Ro died two years before I was born. He succumbed to leukemia, but until the end he thought it was a “tropical disease” or recurring malaria from his days in “the jungle.”

In that brown envelope of possessions Ro brought back from the war are a number of documents that were never folded or marked, but lovingly saved.

There’s a sepia postcard of the S.S. “Ormande,” the ship that evacuated POWs out of Rangoon, Burma. It’s an elegant image of a majestic vessel, imperial and imposing just like the British Empire was then. On the reverse side of the postcard are the places the ship docked on the way home. Rangoon. Colombo. Suez. Southampton.

Ro returned on October 22, 1945. He was 28.

I am named for him. Robyn. Robert.

I realized during my short trip to Changi that I had within me, for good or bad, the essence of a red-headed Englishman who survived.