“‘Cause it’s a bitter sweet symphony, this life.

Try to make ends meet

Try to find some money then you die.”

The hit song by British band The Verve is playing on the car radio as we drive into Pazardzhik, a small town just over an hour from Bulgaria’s capital city Sofia.

The lyrics are poignant because we’re here to interview a man who’s no stranger to life’s ups and downs – a former Olympian who was on top of his game a year before “Bitter Sweet Symphony” was near the top of the charts.

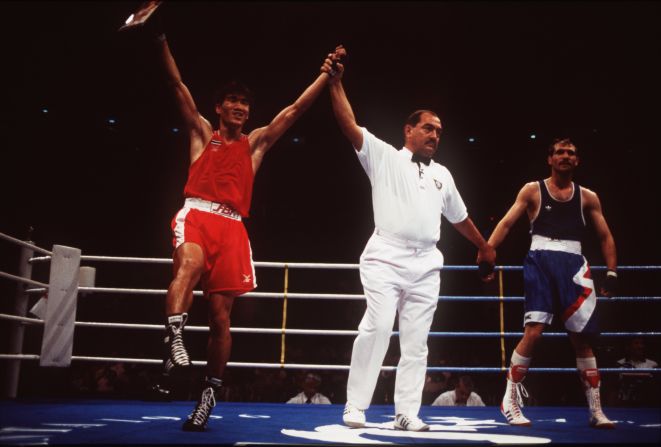

Heading into Atlanta ’96, his third Olympic Games, Serafim Todorov was at his peak as a boxer. Supremely confident, talented and experienced, the 27-year-old cruised through to the featherweight semifinals, where he faced a teenage American.

Todorov says he underestimated his opponent and quickly realized that Floyd Mayweather was a “really good” boxer. Still, the Bulgarian won by a point in a controversial decision that sparked U.S. protests – and the referee initially raised the American’s glove.

It was the last time Mayweather lost in the ring – he is now unbeaten in 47 pro fights – but Todorov’s victory was quickly followed by the moment that completely changed his life. A moment that he bitterly regrets to this day.

While waiting to be tested in doping control, Todorov was approached by American promoters and offered a lucrative professional contract. He turned them down because he was happy with his successful amateur career and was confident of going on to win Olympic gold. He never did.

Instead, the promoters signed up Mayweather, who is now one of the richest athletes on the planet, having won world titles in five weight divisions. Some reports say he will earn $180 million from fighting Manny Pacquiao in Las Vegas on May 2.

Serafim Todorov: The forgotten boxer

Todorov – who retired in 2003 after a handful of pro fights – gets by on state handouts of less than $500 a month.

Now 45, Todorov doesn’t stand out from the group of men waiting for us outside a Soviet-era style apartment block in a rundown corner of Pazardzhik. It’s drab and a little bleak, but not sinister. Kids run around, noisily and happily, on nearby waste ground.

Todorov is wearing bright blue trainers, jeans and a gun-metal gray bomber jacket, with the collar up, over a T-shirt. I am not tall, but he has to look up as we shake hands because he slightly bows his head, peering at me with narrowed but not unfriendly eyes. His skin is weathered and tanned.

His apartment is very tidy and clean. It looks like he has cleared up for us, the way you would before showing people around your home when it’s up for sale. There are bottles of water, nuts and chocolate laid out on the living room coffee table for us to snack on.

It soon becomes clear that Todorov is not trying to impress us. He is simply a kind and generous guy who has experienced being a superstar athlete but understands even better what life is like when all that adulation disappears.

He is just happy to tell us his story.

At his best, he says, based on stats from Germany and Russia, he was regarded as the best pound-for-pound fighter on the planet – the way Mayweather is often described today.

After beating Mayweather in Atlanta, but failing to win the final, Todorov became depressed. “I drowned my sorrows in alcohol,” he tells me, recalling the aftermath of his loss to Somluck Kamsing, who became the first Thai athlete to win an Olympic gold medal.

Even after his career slumped, he was still named Bulgaria’s athlete of the 20th century. Most casual sports fans would pick former footballer Hristo Stoichkov as the country’s most renowned athlete, and Todorov smiles proudly as he talks about the time the 1995 Ballon D’Or winner came over to his table at an awards dinner just to shake the hand of the nation’s favorite boxer.

At times, Todorov appears to physically mourn the man he never became. He grieves for him; the fading of his dream as painful as the death of a family member. Even his Olympic silver medal has disappeared. It was donated to a museum and then lost.

“I can’t change my mold,

No, no, no, no, no.”

(The Verve, 1997)

But there is a glimmer of hope emerging from the gloom of Todorov’s tale.

Our visit ends with a trip to a local boxing gym where he has trained on occasion and coached some of Pazardzhik’s youngsters.

Among the punchbags and mirrored walls, Todorov’s whole demeanor changes. His eyes sparkle and he instinctively moves like the champion boxer he once was, snapping out lightning jabs with barely any encouragement.

He tells me a company is offering to set up a boxing gym bearing his name, meaning a move and a new life for him and his family by the Black Sea.

Before then he’ll watch Mayweather and Pacquiao’s so-called mega-fight, pleased that it has reminded the world of a talent lost to the sport.

“I feel like a winner,” he says, “and I’m proud because Floyd is unbeaten at the moment and I’m really proud that only I was able to beat him. The whole world knows about me now. I feared they might have forgotten.”

Read: Mayweather vs Pacquiao: Referee confirmed, ticket deal made

Read: Wladimir Klitschko: Iron Curtain no barrier for ‘Dr. Steelhammer’