Editor’s Note: Eric Berger is associate professor of law at University of Nebraska College of Law. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. The CNN Original Series “Death Row Stories” returns Sunday, July 12, at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

Story highlights

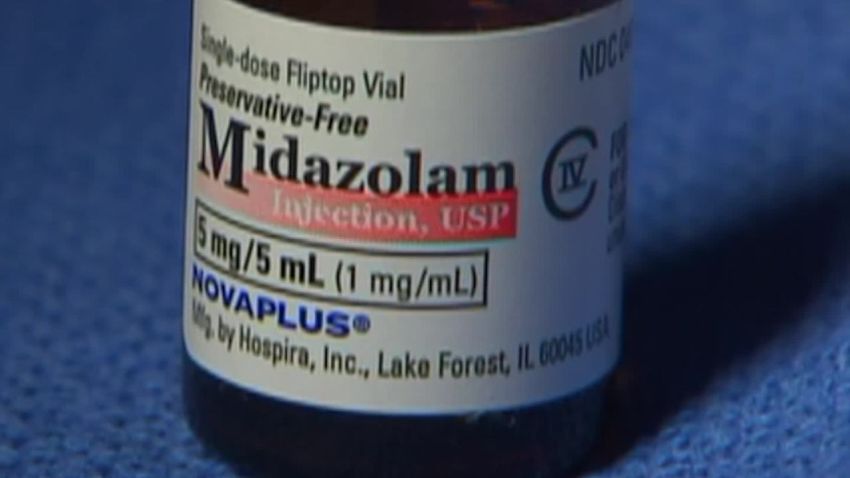

The Supreme Court upheld Oklahoma's use of the drug midazolam in its lethal injection procedure

Eric Berger: The Court's failure to engage with the problems of lethal injection is troubling

The Supreme Court, by a 5-4 vote, upheld Oklahoma’s use of the drug midazolam in its lethal injection procedure. The legal ramifications of Glossip v. Gross are modest, but the Court’s majority opinion had little to do with lethal injection and a lot to do with the death penalty more generally.

Here’s what was at issue: Like many states, Oklahoma uses a three-drug lethal injection procedure. The first drug is supposed to anesthetize inmates so that they don’t feel any pain from what comes next. The second drug paralyzes inmates, so observers can’t tell whether the inmates are feeling any pain. The third drug stops inmates’ hearts.

Everyone agrees that the third drug is excruciatingly painful as it courses its way through an inmate’s veins. At oral argument, some Justices likened it to being burned alive. The constitutionality of the procedure, therefore, hinges on the state’s ability to anesthetize the inmate prior to the delivery of the second and third drugs.

Most states’ first drug is a barbiturate anesthetic, like sodium thiopental or pentobarbital. But drug companies are increasingly reluctant to supply states with those. Consequently, Oklahoma and three other states have used midazolam as the first drug in executions.

Midazolam, however, is not a barbiturate, but a benzodiazepine. Like other drugs in this class, midazolam can cause unconsciousness and unresponsiveness to minor stimuli, but the consensus in the medical literature is that it does not reliably anesthetize people against serious pain. The Glossip plaintiffs therefore argued that the state’s procedure will likely result in cruel and unusual punishment.

The majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, rejected that and in so doing ignored arguments that Oklahoma’s procedure is seriously flawed.

First, the majority faulted the plaintiff for failing to offer an alternative method of execution. But, as the Court concedes, the plaintiff had suggested both pentobarbital and sodium thiopental, but the lower court had deemed those drugs “unavailable.” However, Oklahoma’s neighbor Texas uses pentobarbital and has executed nine people this year alone. Moreover, Oklahoma itself has several different active execution protocols, including a new one substituting nitrogen gas for lethal injection. The state, in other words, had other potential methods of execution, but the Court still didn’t want to confront midazolam’s risks.

Second, the Court deferred to the trial court’s factual findings, because they were not “clearly erroneous.” It is common for appellate courts to defer to trial court findings of facts specific to the case before it. Appellate courts, for instance, usually won’t disrupt a trial court’s findings that a party signed a contract on a particular date or deliberately set fire to his barn. But midazolam’s anesthetic properties are facts of a different sort, because they transcend the particular legal dispute and could recur in other cases with different parties and issues.

The trial court’s findings, therefore, are less appropriate for such reflexive deference. Nevertheless, the Court hid behind the trial court’s questionable findings and refused to engage with evidence of midazolam’s dangers. By contrast, in her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor carefully examined the scientific literature, which concluded that midazolam “cannot be used alone … to maintain adequate anesthesia.”

Whatever one’s stance on capital punishment may be, the Court’s failure to engage with the problems of lethal injection is troubling.

The Court worried that lethal injection litigation frustrates states’ efforts to carry out executions. At oral argument, Justice Alito went so far as to condemn such litigation as “guerilla warfare” against the death penalty.

In a sense, he is correct. Some capital inmates bring Eighth Amendment challenges to try to delay their executions. But even if the Court is correct that these cases seek to buy the condemned more time, the Eighth Amendment claims still have merit. Indeed, states’ problems with lethal injection are well documented, and several recent botched executions highlight lethal injection’s dangers. The Court’s impatience with capital litigation generally, then, has blinded it to some lethal injection procedures’ very real risks.

The Court did not purport to address the constitutionality of other states’ procedures. And while its decision ostensibly opens the door for other states to adopt midazolam, it is hardly clear that that drug will remain available for executions. Pharmaceutical companies have tried to prevent states from using other drugs in executions, so it is quite possible that the same will happen with midazolam. Nevertheless, the Court’s reluctance to engage carefully with Oklahoma’s procedure indicates its willingness to turn a blind eye to Eighth Amendment values so that states can resume executions.

In a separate opinion, Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, asked whether the death penalty itself violates the Constitution. Reasonable people can certainly disagree about the moral propriety of capital punishment, but, at least for the time being, the majority is correct that capital punishment is constitutional. But just because capital punishment is constitutional in the abstract does not excuse the Court’s abdication of its responsibility to review states’ methods of execution.

The opinions of Glossip v. Gross ultimately address two issues: a momentous one (whether capital punishment is ever constitutional) and a narrow one (whether Oklahoma’s use of midazolam is constitutional). The Court’s error was to conflate the two.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine.