Story highlights

After Occupy protests last year, commemorating June 4 takes on new meaning in Hong Kong

Fewer Hong Kong youth identify with greater democracy movement in China

Tens of thousands of people dressed in black. A sea of candlelight. The roar of pro-democracy anthems sung in Chinese.

Every year, Hong Kong holds the world’s largest annual mass gathering to commemorate the Tiananmen Square crackdown. But after sprawling pro-democracy protests put the city at bitter odds with China last fall, this year’s anniversary takes on a different meaning.

Here’s our guide to understanding the significance of June 4 for China and Hong Kong, and what may happen next.

What happened on June 4, 1989?

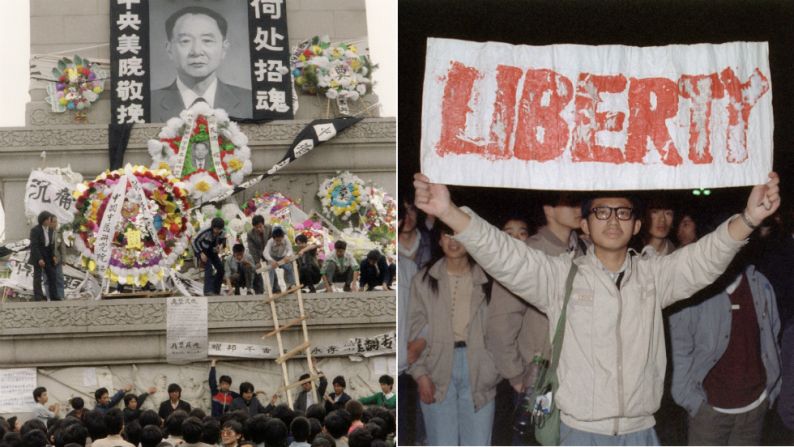

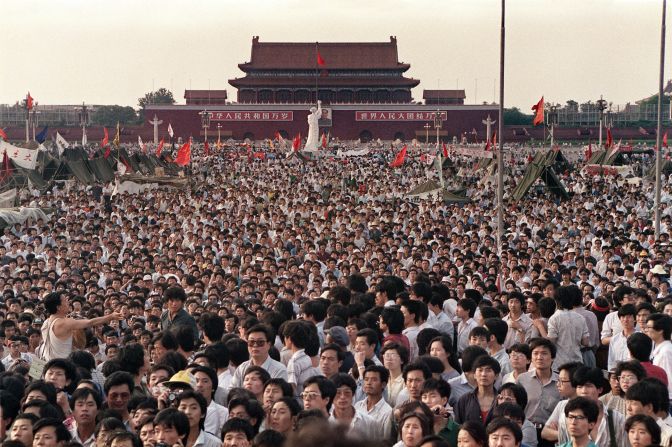

In the spring of 1989, thousands of Chinese students marched into Beijing’s Tiananmen Square to call for democracy.

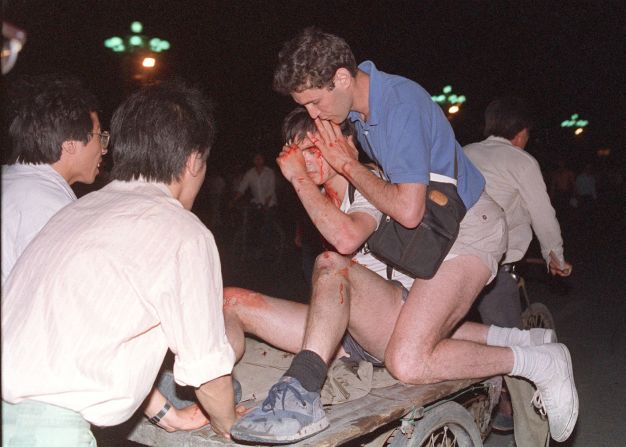

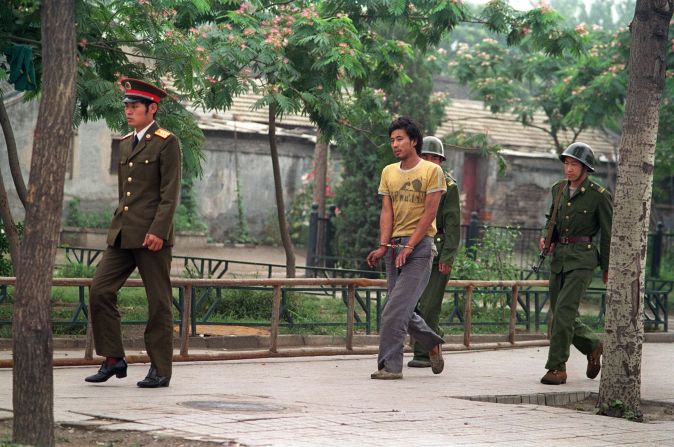

Following weeks of peaceful protests, troops acted on the orders of Chinese Communist Party leaders to open fire on civilians and students in the early hours of June 4, ending the mass demonstrations.

Though no official figure has been announced, the death toll is estimated to range from several hundred to thousands.

What does China say about it today?

Chinese censors have blocked the search results of “June 4” and “Tiananmen Square” on the Internet. If mentioned at all in textbooks and campuses, the crackdown is described as an “incident” or a “counterrevolutionary riot” that deserved to be suppressed.

Last month, a Chinese student studying abroad penned an open letter, co-signed by 10 other overseas Chinese students, calling for students in mainland China to discuss the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

A state-run Chinese newspaper quickly condemned the letter for “twisting the facts of 26 years ago with narratives of some overseas hostile forces.”

How does Hong Kong remember Tiananmen?

Every year on June 4, many Hong Kongers hold a massive candlelight vigil in Victoria Park to honor those killed in 1989 in Tiananmen Square. Some mainland Chinese people attend the vigil as well.

The vigil is also a expression of fierce discontent with the governments of China and Hong Kong as participants shout political slogans calling for the overthrow of the Chinese Communist Party and the resignation of Hong Kong’s Beijing-backed chief executive.

In recent years, the crowds have swelled in size as anxiety grows over China’s increasing influence in Hong Kong, a former British colony.

Last year, the world’s first June 4 Memorial Museum opened in Hong Kong.

Why are Hong Kongers struggling against the Chinese government?

When Britain returned Hong Kong to Chinese rule in 1997, the two countries agreed Hong Kong would enjoy a “high degree of autonomy” for 50 years and eventually develop an election system based on universal suffrage. But nobody agrees on what that actually means.

Last year, China proposed letting Hong Kongers vote for their next leader – as long as candidates are first approved by a small Beijing-backed committee. Infuriated by that proposal, pro-democracy Hong Kongers organized massive street protests that paralyzed parts of Hong Kong for 79 days last fall.

Those demonstrations – known as “Occupy” or the “Umbrella Movement” – were ultimately dispersed by police but deepened rifts in the city and angered Beijing.

How is this year’s anniversary different?

Last fall’s Occupy movement birthed a new generation of young pro-democracy Hong Kongers who organize on the Internet, refuse to identify as Chinese and are eager for aggressive confrontation. They’ve lost patience with Hong Kong’s older generation of activists, who identify with the movement for democracy in China but have failed to secure tangible democratic gains for Hong Kong.

That’s why some younger protesters are refusing to attend this year’s mass vigil run by the older activists. Some of them see the goal of building a democratic China – as implied by the remembrance of Tiananmen – as a distraction from their struggle for democracy in Hong Kong.

What’s going to happen next?

In just a few weeks, Hong Kong legislators are expected to vote on the electoral reform proposed by Beijing. But pro-democracy lawmakers have just enough votes to veto the plan, which needs two-thirds majority to pass.

Activists have threatened new protests and Beijing has not banned assemblies related to June 4 in Hong Kong. However, local authorities have made it clear that they will not tolerate Occupy-style demonstrations again.

Meanwhile, rising housing prices and a growing wealth gap exacerbate discontent among many Hong Kongers. Local and international groups also say press freedom has declined dramatically in the city.

No matter the vote’s outcome, new confrontations within the increasingly fractured city are all but guaranteed. Distrust runs deep, and nobody has been able to come up with a compromise acceptable to all sides.