The Supreme Court on Wednesday resurrected a woman’s pregnancy discrimination claim against UPS, sending the case back to a lower court.

The ruling is a victory for Peggy Young, a former driver for the company who claimed the package company violated her rights under the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) and now will have a chance to prove her case in court.

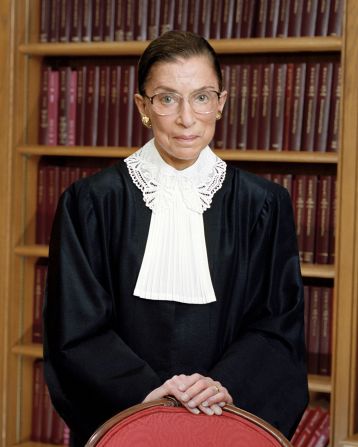

In the majority opinion by Justice Stephen Breyer, five Justices concluded that Young can “create a genuine issue of material fact as to whether a significant burden exists by providing evidence that the employer accommodates a large percentage of nonpregnant workers while failing to accommodate a large percentage of pregnant workers.” Justice Samuel Alito separately concurred in the 6-3 judgment.

“Although today’s ruling is narrow, it’s an important victory for pregnant employees like Young,” said Steve Vladeck, a law professor at American University and a CNN analyst. “The lower court had made it exceedingly difficult for such plaintiffs to show that their employer had unlawfully refused to make accommodations for them because of their pregnancy, but Justice Breyer’s opinion should make it easier at least to present such claims to a jury—if not to prevail on them outright.”

When she became pregnant in 2006, Peggy Young’s doctor told her not to lift anything heavier than 20 pounds for the first 20 weeks of her pregnancy. But Young’s supervisors at UPS denied her request for light duty. She was told that UPS only provided accommodations to three categories of workers: those who had been injured on the job, those who lost their Department of Transportation certification and those who have a disability as defined by the Americans with Disability Act.

UPS said its policy complied with the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) and that it was a pregnancy neutral policy. But Young sued, citing a section of the PDA that says employers must treat pregnant employees the same as others “similar in their ability or inability to work.” Young argued that because UPS did offer light accommodation to some employees who were similarly situated, it must offer her the same accommodation.

In the main opinion Breyer wrote, “Why, when the employer accommodated so many, could it not accommodate pregnant women as well? ” He said he would leave the final determination to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Samuel Bagenstos, a lawyer for Young who teaches at the University of Michigan Law School, praised the decision calling it a “big win not just for Peggy Young, but also for all women in the workplace.”

He said, “The Court made clear that employers may not to accommodate pregnant workers based on considerations of cost or convenience when they accommodate other workers. It’s a big step forward towards enforcing the principle that a woman shouldn’t have to choose between her pregnancy and her job.”

Young drew support from the Obama administration as well as pro-choice and pro-life groups eager to have the court clarify the scope of the law.

Susan Rosenberg, UPS Public Relations Director, issued a statement that it was “pleased” that the Supreme Court rejected an argument that UPS’s policy was “inherently discriminatory.” Rosenberg said the Supreme Court adopted a new standard and that the company is confident that “the courts will find that UPS did not discriminate against Ms. Young.”

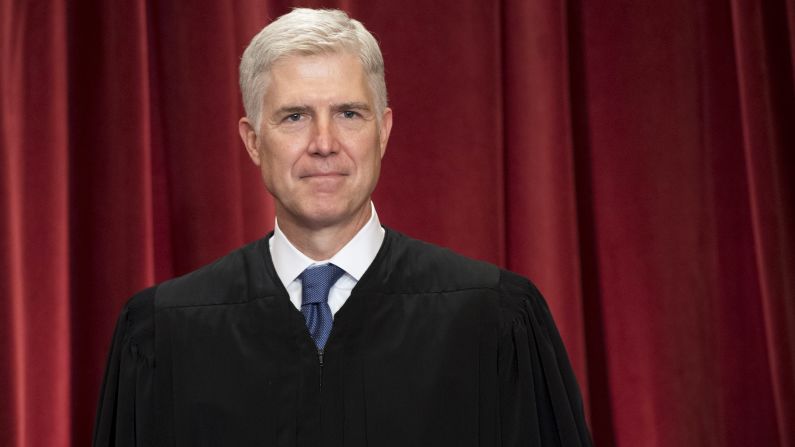

Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy and Clarence Thomas dissented from the main opinion. Writing for himself Kennedy said that there must be “little doubt” that women who are in the work force — “by choice, by financial necessity, or both—confront a serious disadvantage after becoming pregnant.” He called the difficulties pregnant woman face in the workplace an issue of “national importance.” But he said Congress and the States have enacted laws to “combat or alleviate” the difficulties faced by women. “These Acts honor and safeguard the important contributions women make to both the workplace and the American family.”

After the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, UPS, while still defending the legality of its policy, decided to voluntarily begin allowing for additional accommodations for pregnancy related physical limitations as a matter of corporate discretion.