I spent three weeks trying to kayak (and walk) down the “most endangered” river in America, California’s San Joaquin; I quickly learned why no one does that

Videos produced by Brandon Ancil and Cory Livengood

I spent three weeks trying to kayak (and walk) down the “most endangered” river in America, California’s San Joaquin; I quickly learned why no one does that

Editor’s note: John D. Sutter is a columnist at CNN Opinion and founder of CNN’s Change the List project. Follow him on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. E-mail him at ctl@cnn.com. The opinions expressed in this story are solely those of the author.

On and sometimes in the San Joaquin River (CNN) — Halfway through my three-week, 417-mile journey down the “most endangered” river in America, the water began flowing backward and the mud started talking.

It spoke in baritone gurgles, like Barry White trapped in a bong.

You know what this is, John?

No, Barry White mud.

This is QUICKSAND.

*&#%.

Despite my overactive imagination, this ridiculous situation was real: The quicksand -- I didn’t actually believe in quicksand until that afternoon -- bubbled and spat as it slurped me down and held on tight.

It had me at the knees.

As anyone who’s seen “Indiana Jones” or “Princess Bride” can attest, you need a sidekick to get unstuck from quicksand. No sidekick here. I was alone on the San Joaquin River in California’s remote Central Valley -- the forgotten part of the Golden State, where no one thinks of taking a vacation.

I looked to the left to see this Frankenriver flowing backward -- toward the Sierra Nevada, where I’d started this “Mad Max” journey 12 days before.

I had no idea what was going on.

Or how the hell I was getting out.

The San Joaquin, the second-longest river in California, used to support ferry traffic.

This is what the San Joaquin USED to look like. James M. Hutchings, 1862. https://t.co/8lZi1rW4N2 #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/sZWA5IlqEv

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) July 28, 2014

Now there’s not enough water for a kayak and me.

So no one needs to worry about me getting swept away by current today. #endangeredriver @riverkatz pic.twitter.com/ug4PtW8zIl

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

That’s why I’d started walking in the first place, dragging my boat by a rope.

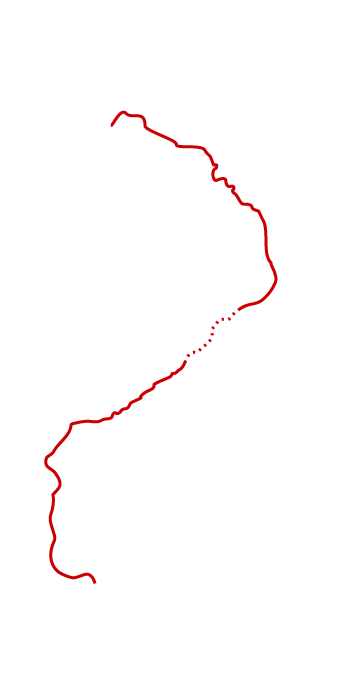

The quicksand was just one of several semi-apocalyptic challenges I’d face on my trip down the San Joaquin, from its headwaters in the Sierras, near Yosemite, to my hoped-for destination, beneath the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

Here’s the route:

The San Joaquin is a river that would flip my boat, steal my camera, throw me into trees, take my food, tweak my muscles, acquaint me with heat exhaustion, scare the s--- out of me, trap me in the mud and leave me hiking for three days across a desert.

It even fertilized me in the middle of the night.

And that’s just the me-complaining part.

Far worse, it also deforms birds (or did, in the 1980s), taints taps, steals jobs, causes the ground to sink irreversibly, kills fish, destroys wetlands -- and harbors shady people with semi-automatic weapons.

Still, it’s somehow also a river that supports a valley that grows 40% of the nation’s fruits and some vegetables as well as more than 80% of the world’s almonds. It’s a hugely important river, but one that’s been engineered almost to death.

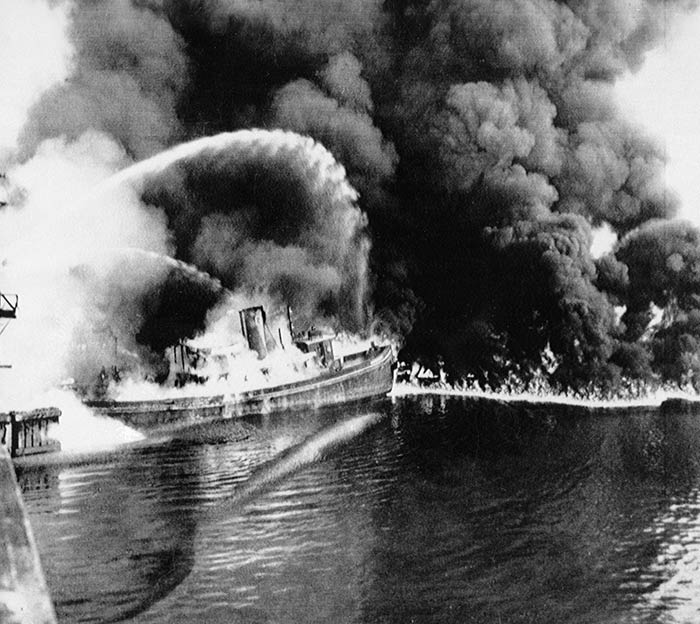

Thanks to the Clean Water Act, rivers don't catch fire from industrial pollution like they used to. Here’s what Ohio’s Cuyahoga River looked like in 1952.

Now we’re in the era of dead rivers -- a time when they’ve been so dammed, diverted and overused that many of them simply cease to flow.

Last year, CNN readers voted for me to do a story on the “most endangered” river in the country as part of my Change the List project. Many rivers could vie for that title. Earlier this year, the Colorado River flowed to the sea for the first time in decades -- and that took an international agreement. The Rio Grande, which forms the U.S.-Mexico border, often doesn’t make it to the ocean, either. And the Mighty Mississippi is so polluted by farms that it feeds a Connecticut-sized “dead zone” in the Gulf. The advocacy group American Rivers, however, chose the San Joaquin as the “most endangered” river in 2014 because it’s at a turning point. Depending on what happens soon, it could become a river reborn, or a drainage ditch.

I had a personal reason for wanting to kayak the river, too.

“Most people are on the world, not in it,” wrote John Muir, the famous naturalist who traveled the Central Valley and the Sierra Nevada and whose journals I would carry with me down the San Joaquin.

I think this notion of being disconnected from the natural world is especially pronounced when it comes to rivers.

We see them when we zip by on highways, maybe. Or when we fly over them. But we don’t spend time with them -- don’t know where they start or where they go. We sure don’t Huck-Finn them these days.

I’m as guilty of this modern river blindness as anyone.

But I wanted to change. I wanted to get “in” this river.

I just didn’t realize quite what that would mean.

I’d been told I was the first person to try to kayak-walk it from source to sea. I’m not exactly a candidate for that kind of river-blazing adventure: I’m sorta-medium athletic and thankfully can swim, but it was my first time to try to kayak on a river, and I had pretty much no idea what I was doing. When I rented a kayak in Oakland a polite, granite-shouldered woman asked me about my “kayaking regimen.”

Um … regimen?

My shoulders are less granite, more Play-Doh.

Stuck in the quicksand out in the middle of the Central Valley, still about 150 miles from the Pacific Ocean, it wasn’t hard to see why no one travels the San Joaquin.

It’s not your mother’s river.

And certainly not one I expected to love.

Darin McQuoid -- a professional kayaker who talks in surfer-speak; throws himself, willingly, off 80-foot waterfalls (tip: go nose first); and carries a polka-dot, Hello Kitty wallet, you know, just to be incongruous -- joined me on a hike to the mountain headwaters of the San Joaquin, high in the Sierra Nevada, the shark-tooth range along California’s eastern border.

Our destination was about 9 miles up, to elevation 9,833 feet.

We took the “River Trail,” and set off around 3:30 p.m.

Whitewater kayakers know rivers better than perhaps anyone, and Darin is one of the only people alive who has seen some of the upper sections of the endangered river -- a part that, to my surprise, remains remarkably wild and deadly.

He spends so much time with water that he’s learned to trust its familiar melodies and rhythms. That’s one reason he’s able to careen through uncharted waters with a reasonable expectation of survival: He sees things in the river others can’t.

Take “The Crucible” as an example. That’s the nickname for a particularly hairy stretch of the upper San Joaquin, where the river splits into three strands -- one of which, at any moment, will dump you on a pile of rocks and kill you.

Which path? That changes all the time, and the cliffs along the river are so steep that it’s impossible to scout the location and pick a route in advance.

Clearly these are not waters for a first-time river kayaker, or even for most experts. And in case I haven’t made this abundantly clear: I am definitely no expert.

So, I wouldn’t be able to float the very top section of river. I could only hike to the headwaters. Kayaking (and more walking) would come later.

True to its name, the River Trail follows the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin (there are three branches of it up here) through a fir-covered valley at the bottom of stunning granite peaks. For miles, though, I didn’t see the river. I noted the Oompa-Loompa-colored tree trunks, roots the size of thighs.

Then I heard a distant rumble.

The river. Out of sight, down in the valley.

“Sounds like a highway,” I said.

Darin’s reply was casual but profound.

“Highways sound like rivers.”

It was my first glimpse at what a river-first mindset can do for a person. Darin’s life is tuned to the water in a way that’s foreign but alluring to me. If you ask him where something is, he answers by the watershed rather than by the road or county. Like: Oh, that’s on the Rogue. Or: Near the Kaweah. Or: Upriver of that. He’s fully fluent in “cfs” -- cubic feet per second -- which is how whitewater kayakers and scientists measure the flow of a river, its speed and strength.

After his comment, I started listening harder: I heard the rattle of timpani drums as the river dove into canyons, the gentle high-hats as it wandered through meadows.

About 7:30 p.m., with stars starting to poke through the sky, we scrambled up a rocky path to the verdant shore of the headwaters.

This is the scene that emerged:

This is Thousand Island Lake. Official headwaters of the #endangeredriver. And not named for the salad dressing.. pic.twitter.com/UQrMnSauPd

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014

Thousand Island Lake.

Definitely not named for the salad dressing.

This is the kind of landscape that screams with the force of a thousand gospel choirs. The lake is gemstone blue -- and pocked with tiny, moss-covered islands, each a Seurat painting of red and orange and green, set on a charcoal backdrop.

The cool air smelled of fir and was as thin as Prince William’s hairline.

It just didn’t seem real.

I walked up to the shore to make sure -- dipped my hand in the frigid water. It was that numbing sort of cold that makes your arm feel like a phantom limb. I thought about jumping in the lake -- baptizing myself in the water that would carry me toward San Francisco. But as soon as I pulled my hand out, it started to throb in the cold.

I looked up to the mountains, saw the snow on Banner Peak, and realized my dip would have to wait.

I felt such conflicting emotions in the moment.

Gratitude that I was able to witness this pure and delightful scene -- a river intact, one of Muir’s “glorious landscapes now smiling in the sun.”

But I also was offended for the water. I had some sense of what would happen to it in the scorching valley below.

Darin and I set up camp within earshot of the lake.

That's @DarinMcQuoid at our camp last night. He's one of the few who has kayaked the upper rapids of #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/8S1LWwO5r2

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014

And just before dark, another hiker joined us.

Peter Vorster is a spritely hydro-geographer (“I invented that term!” he told me, beaming) from the Bay Institute, a group that studies this watershed “from the Sierras to the sea.” I’d asked him to join us on the mountain. He arrived a shaken-up soda can of a person -- just literally bursting with stories.

It was easy to see how much he loves this river; his enthusiasm was infectious.

As we flipped on our headlamps and started cooking dinner, stars lighting up the sky, Peter talked about his previous experiences hiking in this part of the Sierra. Once, when he was a teenager, he didn’t bring a tent because he wanted to sleep under the night sky. It started raining, and he shivered through the night -- going through all the stages of hypothermia, wondering if he’d live.

Most people would take that as a lesson never to trust nature again, or never to camp without a tent, at least. Not Peter. He didn’t bring a tent this time, either.

He couldn't bear to have a piece of nylon between him and the stars and the river.

His love for this place is that psychotically strong.

Peter has devoted his life to studying this watershed -- has been doing that essentially since he graduated from Berkeley in the hippie years. He helped me see this journey in a new way that was both exciting and frightening.

I especially loved one analogy he used.

The best way to understand this river, Peter said, is to piss on it.

Pee all you want, and your urine won’t reach the ocean.

Love how Peter explains watersheds: pee over there, it goes to LA. Pee behind us - fertilize the Central Valley. pic.twitter.com/DHUb8By14p

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014Instead, it’ll get “diverted” and “wheeled,” in the parlance of water nerds out here, through California’s massive plumbing system. State and federal governments built a dizzying network of dams, pumps, canals and aqueducts in the wake of the Great Depression. The goals were logical enough -- create jobs and make the Western desert “bloom” with farms -- but the costs were extraordinary.

Eighty-percent of the water that’s used in California goes to farms, and some of it travels 600 miles to get there. Nearly a fifth of California’s energy use goes toward moving water around, including the power needed to lift it 2,000 feet over the Tehachapi Mountains, toward Los Angeles.

In the San Joaquin Valley, some 95% of wetlands have been lost. And since the state allocates eight times the amount of water that typically flows through the system, the river runs completely dry in its midsection all the time.

I think Peter was a little disappointed I didn’t immediately test his watershed-as-piss-conduit theory -- but I definitely got the point.

My urine, and my boat, would likely dead-end into a farm.

They’d hit a 40-mile stretch of river that’s always dry, by design.

As temperatures plunged and the sun vanished, the rail-thin, 60-year-old scientist told me about California’s “pleasure boating” rule, which says, essentially, that a river is part of the public trust if it can be boated. There’s a similar rule on the federal level -- with the Supreme Court ruling that rivers are protected under the Clean Water Act if they can be shown to be “navigable.” There’s a fascinating history of people using these rules to try to argue broken rivers should be made whole again. In 2008, for example, boater George Wolfe traveled the Los Angeles River -- which is basically a drainage ditch -- out to the sea to prove it’s still a vital waterway.

Helicopters chased him down.

“GET OUT OF THE RIVER NOW.”

But he made it to the Pacific.

His journey “opened up access to a long-neglected waterway,” according to a description on his website. And, in 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency declared the Los Angeles River a navigable river.

The San Joaquin has federal protection. But, talking to Peter, I realized my journey could be seen as a symbolic plea to make the river whole.

A live-tweeted protest.

If only I actually knew how to kayak.

“How deep our sleep last night in the mountain’s heart, beneath the trees and stars, hushed by solemn-sounding waterfalls and many small soothing voices in sweet accord whispering peace!” -- John Muir, from “My First Summer in the Sierra”

The next morning, Peter, Darin and I hiked down the mountain, across a snowfield, past glacial lakes and, at one point, through the river, the water rushing around my calves, stealing my footing and nearly yanking me in.

It was brilliant.

I’d started to love this river -- its wild, free spirit.

But the mountain high wouldn't last long.

Soon, I was back on the Central Valley floor.

Forecast: sauna.

I'm usually not so obsessed with temperatures ...but holy hell. Just pulled into Fresno. Saw two people out walking. pic.twitter.com/se0xW8UI6c

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 9, 2014

It’s a place where water is money, not beauty.

And where its distribution shapes every aspect of life.

It’s also where I’d finally have to test my kayaking abilities.

Step one was figuring out where to start.

As it tumbles down the Sierra, the San Joaquin churns the turbines of about 20 hydroelectric dams, earning it the title of the “hardest-working water in the world.” The last and largest of the dams is called Friant, just outside Fresno, a 500,000-person agricultural outpost at the base of the mountains. The dam was completed in 1942, designed, in part, to hold back water for farms.

Experts told me I’d have to start below it.

Friant dam, the nerve center of the #endangeredriver. You get misted standing here. pic.twitter.com/vXOMGOwWrB

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014

I toured Friant Dam the day before I set off -- stood on top of it and watched a rainbow materialize from the mist. I could see the river below -- my intended path -- and also could see that the dam shuttles water in three directions.

One route follows the natural channel of the San Joaquin.

That'd the #endangeredriver from the top of 318 foot Friant Dam. Note the rainbow. pic.twitter.com/EdgoAPZVgs

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014

And two routes go to farms -- some of them hundreds of miles away.

Friant Kern canal sends water 152 mi south of here to Bakersfield Cali. Mostly to farms. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/cu0PY4fd2f

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014

I started to see what Peter was talking about. I imagined my urine trying to figure out which path goes to the ocean.

It’s not so simple here.

Nationally, there has been a concerted push to remove dams like those that block the San Joaquin. These concrete cathedrals, as they’ve been called, hold back tons of sediment, starving the wetlands and deltas. Land is disappearing from the Mississippi Delta, for example, at a rate of one football field per hour because that river has been so dammed and constrained. The dams also kill fish. The San Joaquin used to be home to the southernmost Chinook salmon run in the world, with an estimated 200,000 to 500,000 spring-run salmon, according to Gerald Hatler, from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. But the migration route has been destroyed; thousands of fish are being released into the river, but they can’t survive here now unless they’re put in trucks and driven around a dry stretch of the San Joaquin -- and its multitude of dams.

That sounds like a joke. But fish actually are hitchhiking on trucks.

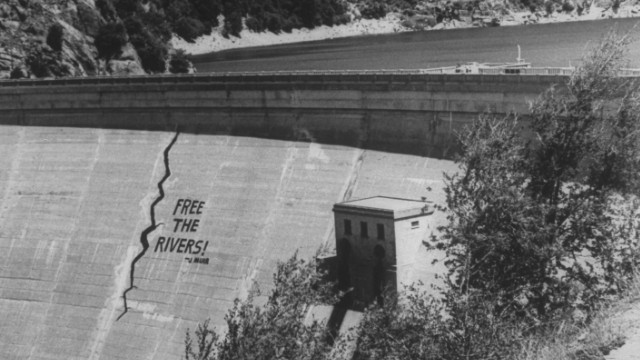

Elsewhere, activists have painted dams with the famous John Muir quote -- “Free the rivers!” -- in hopes they’ll be taken down.

More than 1,000 U.S. dams have been removed in recent decades. But here, new dams are being proposed -- one just upstream of Friant, called Temperance Flat. I took a boat out to the proposed site with representatives from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which argues the new dam would “create” water that could be used to help fish and farmers (they wouldn’t say in what proportions).

My stomach sank as I saw a beautiful canyon that could be drowned.

So eerie. All of this would flood to the hilltops if a proposed dam were built. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/VTOycBXEXx

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 13, 2014

A bureau manager told me nothing would be lost. Only “replaced.”

But dams kill rivers -- and there are some 75,000 dams in the United States today.

“Think about that number,” former U.S. Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt said in a 1998 speech. “That means we have been building, on average, one large dam a day, every single day, since the Declaration of Independence.”

It’s time for that era to come to a close.

Below Friant Dam, I expected the San Joaquin to be tame -- a river on Ambien.

But because of a strange dispute between farmers and the dam’s operators, far more water than usual was being allowed to flow past the dam. It looked like dough shooting out of a pasta maker as it flew into the riverbed.

This river still had some life in it.

Enough to make me plenty nervous.

I found myself wanting to control the river.

I’d been up all night worrying about it by the time I loaded my boat -- a 14-foot, green-and-blue Jackson Journey -- full of colorful and carefully sealed synthetic bags designed to keep my gear dry: clothes, sleeping bag, sleeping pad, tent, GPS device, notebooks, headlamp, food, John Muir journals, two cell phones (yes, I’m that guy) and two GoPro cameras.

Me this morning trying to make all the damn gear fit. Boat basically is the equivalent weight of an elephant. pic.twitter.com/MBKu4u8phU

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 15, 2014

I didn’t think about the fact that I’d still have to carry it down to the water.

It must have weighed 150 pounds, and I had to enlist someone’s help to haul it down a zigzagging path to the river’s edge. It was only a matter of yards, but we had to stop at least five times to rest.

My hands already were raw, and I hadn’t started paddling.

I invited five new friends to join me for Day 1 on the river, thinking there would be safety in numbers. They included a public radio reporter, an irrigation district manager and three river advocates.

Here is our San Joaquin gang for the day! River advocates, a journalist and irrigation district. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/M7sWZ0Zfyc

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 14, 2014

I was the last one in the water, on account of all my gear, which I’d shoved into two portholes in the boat, one in front and one in back. By the time I’d actually squeezed myself into the “cockpit” of the kayak -- the wobbly version of a corset fitting -- everyone else was already paddling in circles, like sharks in waiting.

“Do you want to warm up a bit?” one person asked.

No, I said, nervous they’d spot my ineptitude. Besides, I figured, I would have plenty of time to “warm up” in the coming weeks.

We set off, me near the back, and immediately hit a set of rapids.

I bounced through them, not realizing until later that my paddle was actually upside down, and therefore not pulling much water.

I got lucky, missing the rocks and ending up in a slow-moving pool of water.

It surprised me how amazingly fun it was.

With the water moving fast, I didn’t have to paddle much -- just stick my blade in every now and then to avoid running into trees.

The day zipped by, and was so perfect I wondered aloud whether a PR person with connections in the natural world had set all this up.

We saw two bald eagles.

An ancient mortar and pestle carved by American Indians.

A baptism.

“Praise Jesus!!”

And a wedding at river right.

Joel Salazar, father of the bride, carrying a crystal-topped cane, told me he didn’t know the San Joaquin had been named the “most endangered” river in the country.

“I don’t know who says it’s a dead river,” he told me.

Well, me.

I’d been saying that.

One day on the water, however, had shown me a river that was very much alive -- physically and spiritually. The water was blue and crisp and cold -- I could tell it was the same water that came from the snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada, up at Thousand Island Lake. It still felt alive. I dipped my arms back behind me to cool off, and the scorching sun vanished. Our group’s conversation kept coming back to the religious power of water, too. Ezra David Romero, the radio reporter, was baptized in the River Jordan. Chris Acree, a Buddhist, said there’s a reason the Buddha is often pictured with a lotus flower. They grow from muddy water. They rise above their surroundings to achieve enlightenment.

When we finished paddling, 16 miles for the day, it was a celebration.

Man on shore: "Where are you going?" Me: "San Francisco." Sarcastic man: "Yeah good luck with that." #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/PU6GfklWwH

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 15, 2014

I felt completely at home, and totally in control.

I camped alone on an island, technically still in the city of Fresno but feeling a world apart. Ezra told me there was a bar just above the bluff with 50 beers on tap. Normally, that would have sounded amazing, but I didn’t want to stray far from the river. I set up my tent, inflated the sleeping pad, propped up my solar charger to boost the battery on my phone, since I’d been tweeting all day, cooked a simple dinner of noodles and wrote in my journal as I watched the sun set.

The sky was playing jazz.

In my tent, maybe two hours later.

That noise …

What is THAT NOISE?

I was too afraid to crawl out to see, so I turned my headlamp to blink-so-as-possibly-to-scare-away-animals mode, picked up a book and started banging it against the floor of the tent to get the intruder’s attention.

SCRATCH - SCRATCH

I was so freaked out that I couldn’t sleep. I wrote this in my journal: “Something is rummaging around outside the tent. Hope it’s not eating my food. Is it in the tree? Does it see me? I hear the rustle of leaves. Across the lake, there’s an electronic-sounding GROAN-GROAN-GROAN that might be a water pump… or a wild boar.”

That sound, I later learned, was actually a bullfrog.

I woke up the next morning to find the intruder had eaten about a third of my food, including a treasured loaf of sourdough and a bunch of oatmeal.

I’d like to tell you it was a mountain lion or a bobcat, since I’m told those do live in the general area. But I’m guessing it was a raccoon.

I laughed it off, pulled down the tent, boiled some water for coffee, and packed up the boat, ready to start a new day, fresh again. But I’d be lying if I said it didn’t make me feel vulnerable. What ELSE is out there, unseen and hiding in the night?

What if it had come for me instead of the food?

On the water, things got a little better.

I was joined by Tom Biglione, a naturalist-plus-insurance-company-owner who heard about my trip through a nonprofit and wanted to come along for part of it. He’s the kind of person who picks milkweed seeds in his free time so he can plant them back home in Sacramento. Why? He knows monarch butterfly larvae feed only on that plant. The name of his insurance and financial services company is River View. He says he named it that to be a “reminder for why I work.”

Tom, 66, provided a generous amount of logistical help -- and a great deal of river know-how. I told him about how much fun I had the day before, flying down small rapids. I also admitted that, when the water wasn’t doing the moving for me, I had no idea how to make the kayak travel in a straight line.

I kept bouncing from bank to bank like a pinball.

Tom chuckled in a knowing, fatherly way and told me I’d figure things out over time.

That the boat would start to feel like part of me.

"The more you work in a boat like that the more it becomes part of you. You're wearing it" #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/2yPEHIukTv

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 15, 2014

That couldn’t have seemed further from the truth.

It felt like a cancerous growth.

Tom can identify pretty much any bird or plant, so we spent the morning on the river, him in a canoe, me in the kayak, playing a game of “What’s that?”

It probably wasn’t a very fun game for him.

It went something like this:

Me: “What’s that black bird over there?”

Tom: “That’s a blackbird.”

That’s a literal example, by the way.

Tom taught me to distinguish plain blackbirds from red-winged blackbirds (their call sounds like AOL dial-up Internet); great blue herons (modern pterodactyls with grumpy-old-man attitudes); and great egrets (elegant white birds).

The same goes for trees. I’m horrible at identifying plants, and I think that’s true for almost anyone who’s younger than 40 and lives in a city. But a whole new world starts to open up when you learn this stuff.

Tom taught me to ID sycamore (white bark), valley oak (like on golf course logos), eucalyptus (white-ish bark that’s so soft and papery it’s peeling), Hooker’s evening primrose (an ephemeral yellow flower, meaning it only blooms for a day; and named for a botanist, not an actual hooker, which made me like it less), willow (like silver tinsel), mule fat (white fuzz, and used to fatten mules, apparently) and cottonwood (my new favorite; you can tell them by their lime-green, heart-shaped leaves that are so thin, almost like cellophane, that when the wind catches them right they make the sound of applause.)

Each birdcall added a layer of complexity and excitement. I started to see reality TV show plots in their interactions -- the way the red-winged blackbird will swarm a much-larger hawk to keep it away from its young. Or, downriver, how the killdeer (named because its call sounds like someone yelling “KILL DEER! KILL DEER!”) pretends to have a broken wing to protect its gravel-shaped eggs. And the brown-headed cowbird. It actually abandons its young in the nests of other birds, which are either too dumb or too loving to notice and so raise the cowbirds as their own.

Scientists call them “nest parasites.”

As Tom and I navigated a forgiving stretch of river, my paddle still upside down, he taught me about several virtues of “reading” the water.

It sounded like nonsense at first, but he assured me it would save me energy, so I listened. My shoulders were already getting sore.

Among the watery things I learned to “read”:

1. Eddies: mini-whirlpools that cause your boat to stall, kind of like driving over a banana peel in “Mario Kart.” They’re fairly easy to spot if you know to look; and if you see them coming you can use them to your advantage.

2. Strainers: Any object that is stuck in the middle of the river: a tree branch, a rock, a car (I saw lots of those, actually). Rule: ALWAYS AVOID STRAINERS.

3. Currents: Water in this part of the river was flowing at maybe 2 mph, but it’s not even. When the river splits into two channels, which happens often, you look on the surface for bubbles or leaves and see which side is moving faster, or which direction more of the water is choosing to take.

There are finer points to it, but the moral is to go where the water wants you to go rather than creating your own agenda. You have to work with the river, Tom said.

Not against it.

If only I’d listened.

After lunch, I came upon several tests of these theories. The first was a bridge -- a roaring highway bridge, which technically was closed to boats.

Um .... Ok? pic.twitter.com/WzcMPq6uKk

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 15, 2014

Tom followed the water between two bridge posts on the far left side of the river, anyway. Nets and wood planks partially blocked the path, and he had to duck down in his boat to slip beneath construction equipment on the underside of the bridge.

I tried to follow, ran into a cement pillar, spun at 45-degrees, ducked, and somehow made it to the other side unharmed. I was glad to have a life jacket.

I muttered several words I can’t repeat here.

The second lesson seemed less threatening, but was worse.

The river forked, and I told Tom I thought the dominant flow went left. He disagreed and went right, which should have been a sign of things to come.

My “read” of the river took me careening into a thick set of trees.

The channel was a dead end, and the water was accelerating through it.

Wrong turn ... This is why you're supposed to "read" the water ... pic.twitter.com/0LB1kfnrqx

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 15, 2014

The kayak got stuck on top of a log. I couldn’t paddle backward fast enough to get dislodged (I also hadn’t had to paddle backward yet, and didn’t really know how). So Tom came to the rescue, climbing through a thicket, with a saw (who has a saw?) that he used to cut down a tree branch blocking my way. I fidgeted around for about 15 minutes, trying to get off the log, and eventually set myself free.

I turned on the GoPro on my head as I went barreling forward.

That’s when the real problem started.

I shot through the thicket (there literally was no channel), ducking to protect my head. I made it to the other side but was so out of balance and out of sorts that when I tried to stop up against Tom’s canoe, my cockpit filled with water.

I flipped -- felt the shock of the chilly water going up my back.

Tom: “You’ve officially been strained!”

My baptism in the river.

Lost: The GoPro, along with several days of footage.

Lesson: This supposedly dead river is in control.

The San Joaquin is just the start of the Central Valley’s problems.

This forgotten part of California -- the “Other California” as it’s been aptly called -- is also home to some of the worst air quality in the country (three of the five worst U.S. cities for smog -- Visalia, Bakersfield and Fresno -- are in the valley); groundwater pollution so bad that some people, including Eunice Martinez, whom I met, can’t drink from the tap and must keep jugs of bottled water by the sink; and extremely high rates of poverty.

If Central California, comprised essentially of the San Joaquin River basin, seceded from the rest of the state, it would become the poorest state in the nation, with a per capita personal income $150 lower than Mississippi’s, according to a report compiled for the California legislature.

It’s more West Texas than West Hollywood.

A far cry from Berkeley or Silicon Valley.

There’s another Central Valley superlative most people talk about: Fresno, the agricultural hub of the valley, has the worst public parks system in the nation, according to a report from the Trust for Public Land.

Maybe that sounds like nothing compared to tainted drinking water, choking air quality and extreme poverty. But when I heard that stat, the valley started to make more sense to me. This is a place where people are thirsty for life. The river, meanwhile, is almost completely cut off from people who don't own land.

Tom and I paddled up on one park where hundreds of people were cooking, laughing and swimming along the banks of the river on a weekend evening.

"You're in a canoe but different!!" pic.twitter.com/zGBIojLZEz

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 16, 2014

Rosa Alcaraz, 23, is out here with 14 family members celebrating the weekend. She works in an almond packing plant pic.twitter.com/o5ubU879TJ

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 15, 2014

But places like that are few and far between.

It was almost impossible for me to find places to camp because so much of the river is privatized. And, at times, I had to stop for lunch on riverbanks that likely were owned by farmers.

No wonder people don't care about the river’s problems.

They don’t know it dries up not far from here.

"Jesus... Man I've lived out here my whole life and I've never heard of that." - Sergio Gonzales, 19, on dead river pic.twitter.com/SEFxLV1dco

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 16, 2014

The Central Valley grows our food -- and inherits our problems.

It’s a hardscrabble place that could use a healthy river to lift its economy, and its spirits. I met people along the San Joaquin who would like to see river tours, fishing contests, festivals and community gatherings. (The Natural Resources Defense Council helped host a “salmon festival” near Fresno in 2013, but that seems like wishful thinking for a river without a real salmon population.)

None of that seems likely here.

Even where the river flows, access is largely forbidden.

Some people don't know it exists.

Floating through the Central Valley on the San Joaquin River, it’s hard -- probably impossible -- to imagine what it looked like before the dams, canals and diversions. I found myself stuck in a loop of “supposed tos.” Is that riverbank “supposed to” be so steep, or is that a manmade levee that’s trying to keep the water off that farmland? Is this how fast the river is “supposed to” be moving, or would a “normal” flow be much quicker? I haven’t seen any fish here: Is that normal or not?

I looked at some historic photos and drawings to get a sense of what the San Joaquin is “supposed to” be -- a river that supported salmon and ferryboat traffic.

But the best way to really get the feel for it is to talk to Walt Shubin, an 83-year-old with a cauliflower nose and a Hemingway hardness about him.

He’s one of the few people who remember the San Joaquin as it actually was.

Walt lives on a small, organic grape farm just off the river, and he let me stay the night with him because -- surprise -- there was no public place for me to camp in the area. He offered me a “margarita” -- actually a wine cooler in a blender, but it tasted like heaven -- and a sandwich with a side of cucumber-tomato salad, picked from his garden. I was exhausted from the day’s paddle but we talked for hours at a two-person table in his kitchen, books and magazines, most of them about the river, piled up around us. The NBA finals were on TV.

“That LeBron James is a goddamned bully,” he said.

Walt’s not one for pulling punches.

In the first two minutes of our meeting, he called his farming neighbors “ecoterrorists” for their overuse of water and harsh chemicals. Others, he calls “Wall Street farmers,” since large corporations -- among them, according to a report from the Oakland Institute, insurance giants and equity firms from Silicon Valley to Switzerland -- have bought up fertile Central Valley land, contract farming it at a profit and, in the process, helping to dry up the San Joaquin.

“You can’t live without water. It’s the most important thing in the world,” Walt said. “There’s enough water for everyone’s needs, but not enough for a few rich people’s greed. And that’s what we have here: greed.”

Walt has watched the changes for almost a century.

“I’ve had a love affair with this river since I was 5 years old,” he told me. At age 12, he built his first canoe. The river was a child’s playground -- and he remembers marveling at the water and the many species it supported. He recalls a time when salmon “ran” up the river in such a thick pack that it seemed you could skip across the river on their backs, without getting wet.

“Just goddamn. Like I say, wall-to-wall salmon.”

The river was alive then -- connected to the sea.

Salmon, I learned, require a connected river to survive. They’re born in mountain streams, swim out to the ocean, hang out for three years -- and then they do something truly amazing: They swim back up the river, against the current, without eating or resting, digesting their own bodies to the point their fins start to look like webbed skeletons. They’re a rare fish that morphs to survive both in fresh or saltwater -- the aquatic version of a human learning to breathe on Venus.

The salmon only have two goals for this journey, as fish biologist Jon Rosenfield explained it to me: have sex and die. They lay eggs back up in the cool, mountain waters, carefully flip their tails to make a suitable nest in the rocks for them, and then they join the great circle of life by calling it quits. They’ve used all their energy making it back up stream -- and their bodies essentially become “40-pound bags of fertilizer,” as Jon puts it. If you drink wine from California, know that salmon likely had something to do with fertilizing it. Scientists have identified marine isotopes of nitrogen and carbon that salmon have carried up into the fields.

The salmon provided free food, and free fertilizer.

But, along the San Joaquin, that’s basically over now.

When the dams went up, and when the government gave all the water away to farms, the salmon here died, or went elsewhere. Incredibly, they can jump 10 feet (above a high-dive!) but, of course, can’t leap over dams that make no accommodations for them, or flop across 40 miles of desert. There hasn’t been a real salmon run in the San Joaquin since the late 1940s, said Hatler, who manages the river restoration program for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The plan to fix all this -- to connect the river -- is estimated to cost $900 million, said Monty Schmitt, from the Natural Resources Defense Council. Called the San Joaquin River Restoration Program, it’s the result of a lawsuit filed in 1988 by environmental groups, including NRDC, and settled with the government and some water users in September 2006. The restoration program calls for a number of improvements to the river, including fish passages around dams, possible payments to farmers who own land that would be flooded if the river returns, and, importantly, increased flows to the San Joaquin to support salmon. Environmentalists are optimistic, but the effort is in political jeopardy, and critics say it may not be funded to completion.

Consequently, there are doubts salmon again will be able to thrive in the San Joaquin. Walt’s unsure himself. But he’s hopeful.

“The water just ran all over hell,” he said. “It was beautiful. You can’t exaggerate how beautiful. … This whole country was blanketed in wildlife, like you couldn’t believe.

“I’ve seen ducks so thick it blackened the sky.”

Not all his memories of the valley are so dreamy. Walt’s parents emigrated from Russia, fleeing the 1917 revolution. They worked as “fruit tramps” in California, as he describes it, living outside on sheep’s wool blankets, without a tent, and picking grapes. This is the generation chronicled in “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Walt started working in the fields when he was 4 or 5. They worked “dark ‘til dark.”

He’s put similar gusto into his efforts to tell people about the San Joaquin and how magical it once was and how it could be that way again. He writes letters to the editor, makes occasional speeches, and will tell anyone who asks about the river.

Lately, it’s been harder to keep it up.

Walt’s wife died eight years ago, followed by two of his sons. All from cancer. Their pictures memorialize them in the living room, above the sofa.

“All this s---, this cancer and asthma, and all this s---, is connected to the environment,” he said. “We’re poisoning ourselves with all this bad air, bad water.”

Walt has to escape to the mountains because his asthma is so bad from the smog. Up in the Sierra, he can walk for miles, he told me. Down here, a walk to the yard gets him winded. He’s not able to get around as quickly as his mind moves.

And this is strange to write, but Walt told me he was thinking of committing suicide -- “going up to Oregon,” as he put it -- until he got a call from me about the river trip.

The idea of a trip down the San Joaquin -- the whole river, all the way to the sea -- is something he’s dreamed of for years. When I first called him about it he just about leapt through the receiver he was so excited. Told me he wanted to do the whole thing with me if he could. His lungs aren’t up to it, of course. Nor is his body.

We talked maybe a half-dozen times before I arrived in California. He kept calling back to tell me he’d join me -- then, no, no, of course he couldn’t. His health, his heart.

The thought of it was enough to keep him going, though.

A reason for hope.

Eventually, I came to see Walt as the river.

Past prime. On the verge of calling it quits.

But still vibrant, full of life -- a stubborn bastard of a thing.

Walt promised to call to see if I made it to the Pacific -- and not to go to Oregon before that. I told him he’d travel with me in spirit -- that I’d share his stories of a healthier river, a whole river. That I’d think of him often.

The next morning, as I set off on the water, Walt was there to wave. I spotted him again two miles downriver, peeking through the trees on the bank.

The river’s spirit embodied -- and cheering me on.

The longer I spent with the river, the more frustrated I became.

Someone eventually told me my paddle was upside down, but I still couldn’t control the tipsy kayak. I spent so much time trying to correct it leftward that a knot beside my right shoulder blade started screaming bloody murder with each stroke.

"We are now definitely on the portion of the river that usually does not have any water." #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/XefIdB83W4

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 16, 2014

I took a day off the river, both to recover -- I guess this is why you need a “kayaking regimen” -- and also to see what life is actually like in the Central Valley.

Things only looked worse beyond the banks of the river.

I caught a ride from local filmmaker Juan Carlos Oseguera to Mendota, California, where the unemployment rate is reported to be 35% to 40%, but where advocates like Dino Perez, from Westside Youth, an afterschool center, will tell you it’s likely higher. Many of that town’s 11,000 residents are undocumented farmworkers, and the lines for food at Dino’s nonprofit have stretched down the block this summer, he said. That, as Dino made clear, is incredibly ironic. The people who are growing our nation’s food are in need of food assistance. I found that infuriating.

Life is hard in Mendota Ca. Reports of 35-40% unemployment. But I really do like it here. Still has spunk/hope to it. pic.twitter.com/Snyu3YhBdO

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 18, 2014

Dino Perez is trying to help families in Mendota thrive. Need is great. Food lines this year have gone dn the block pic.twitter.com/yx6c6jmaoc

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 18, 2014

Wander around Mendota and you’ll find there are no cantaloupes in the grocery store, even though a sign advertises this place as the “cantaloupe center of the world.” The avocados, a California staple, are from the Dominican Republic and Peru.

Food is imported just like water.

Go to the local pool hall and you’ll meet people like Luis Luna, 60, out of work, wearing a pearl-snap shirt. He tells you “there’s nothing here.”

The reason?

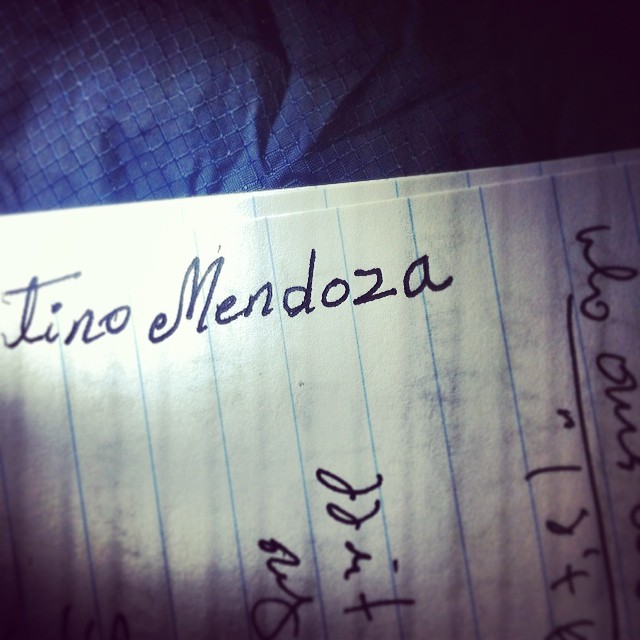

Florentino Mendoza knows.

“There is no water.”

Eighty-two percent of California is in extreme or exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, but no one here needs to look at the forecast to know that.

The land is bone dry.

Jobs are gone.

And wildfires have been raging in the mountains.

This is climate change in action. Farmers reportedly are paying upwards of $1,000 and $2,000 per acre-foot for water at auction, as compared to less than $100 in a wetter year, farmers and government officials told me in interviews.

Only the richest, corporate farmers survive these conditions.

People here are cutting back on groceries to make ends meet. Less water means less farm work. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/aSYG5iefTm

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 18, 2014The drought is expected to cost California $2.2 billion and 17,000 jobs.

Near Mendota, everyone is suffering.

As our conversation was winding down, I asked Florentino to write his name in my notebook, which is something I often do to make sure I get the spelling right, especially if I’m working through an interpreter, as I was in Mendota.

He wrote in neat, deliberate cursive, the ends of the “M” curling like vines.

I complimented him on his penmanship, said it was far superior to mine. He told me that that’s the only thing he knows how to write -- his name.

He never had a chance to go to school, never had that opportunity back home. He fled violence in El Salvador before chasing a number of jobs in the United States.

He landed here, in a town without water -- or work.

I won’t soon forget him.

Nor will I forget George Delgado, once a farmworker like Florentino, who now owns a farm of his own. The trouble is, he doesn’t have much access to water.

“Go back to your history! Go back to the Dust Bowl! Go back to Kansas! … There’s a lot of farmers who aren’t going to make it,” he said. “There are farmers who are going to commit suicide. … You’re working with a gun to your head.”

Yesterday with @jdsutter interviewing George Delgado at his #farm #drought #water #endangeredriver #fightforwater pic.twitter.com/z70op2ZzwF

— Fight for Water Film (@oseguera) June 19, 2014

Worth saying again: it is DRY dry out here. Lots of fields like this. Plowing the dust. #endangeredriver #cadrought pic.twitter.com/u8Lia9MSEw

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 19, 2014

Some farmers are just plowing up dirt. Lots of people with zero or very little water allocated. pic.twitter.com/YqcsAcUmL7

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 17, 2014

In most of the country when you hear references to “the 99%” and “the 1%” it’s referring to wealth. Here, it’s water. This land is useless without it.

A few have bountiful access -- and the rest are left with next to nothing.

Farmers like George are getting creative to try to save the resource. He has installed “drip irrigation,” which is a water-saving technology. The roots of his almond trees are actually from peach trees, because they’re better adapted to the soil. He’s grafted them together, which I’m told is relatively common.

Less helpfully, other farmers are drilling deeper water wells.

Which, as I would learn, is causing the Central Valley to sink.

I caught a ride with Michelle Sneed, a scientist from the U.S. Geological Survey, to a monitoring station where she and a colleague measure how fast the land is sinking. The basic concept is pretty simple: Water out, ground down.

"This is more (subsidence) than we've ever seen here before." Justin Brandt #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/E0esfkqDCz

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 17, 2014But it’s a problem that’s invisible and largely unacknowledged.

At the time of my trip, California was the only state in the Western United States that doesn’t regulate groundwater “extraction,” meaning farmers with deep pockets can drill wells to get to the deepest water. That likely will change, as the state recently passed new groundwater rules. But it’s still an underground arms race.

I asked Michelle to help me picture what’s happening.

She showed me bridges that are sinking beneath canals.

And gave me the measurement of exactly how much the ground here was sinking.

Top of the shovel: that's where the ground was in the 1930s. Thank groundwater depletion. #endangeredriver @usgs @cnn pic.twitter.com/iJr4qKKO0K

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 17, 2014

The top of the shovel is where the surface of the land was in 1935.

Ten feet above where it is now.

In other places in the Central Valley, the rate of subsidence is worse -- the land is dropping by nearly a foot per year near Los Banos, California.

One foot per year.

“The evidence is overwhelming,” Michelle said.

I don’t blame farmers like George for trying to drill for water.

It’s clear, however, there’s not enough to go around.

Without regulation, this water rush won’t end well.

That night, I slept at a canal-side campsite by some railroad tracks. The staff was friendly enough, and I didn’t run into trouble, but it looked like the kind of place where the filmmaking Coen brothers would have someone like me murdered.

The next morning, I continued to paddle toward the ultimate example of this collective myopia: the place where the San Joaquin is dried up completely. I wasn’t sure how I’d approach it. I knew I’d have to walk. Memories of the warnings flashed in my head: the lack of potable water, the possibly hostile landowners.

.@agleader told me, half joking, that I could "die a slow death" trying to muck my way through some parts of the #endangeredriver out here.

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

“You crazy kid! You poor guy!” Mark Grossi, a reporter at the Fresno Bee, told me when I explained the plan. “You go wandering around, you might get shot!”

A farmer told me I could “die a slow death” out here.

I felt alone out there on the water, even though I had company. I could see the Coastal Range -- which Muir called the “blue mountains” -- ahead of me, to the west, near the coast. And, one afternoon, I could see the Sierras, fuzzy cloud-like figures, far behind me. The Central Valley is surrounded on three sides by mountains, and being out there, day after day, especially on the water, makes a person feel like the rest of the world, beyond the borders of the valley, has evaporated.

Like this is all that exists.

I carried my boat around Mendota Pool, where a “water master” in an office miles from there sends the San Joaquin in and out of 20-some channels and canals. Almost all the water from the Sierras is used up by that point, and the state brings in new water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, near the coast. It’s pushed back up this way by two massive government pumps -- capable of moving “enough (water) to fill 170 railroad boxcars each minute” -- that also are responsible for changing the flow of the delta and chewing up endangered fish.

That water already has been polluted by agriculture. It’s reddish brown, warm to the touch, and crawling with algae, which snacks on the chemical fertilizer.

Bottom line: this is not the same water I've gotten to know all these days. That was mostly pumped out and this is in pic.twitter.com/SRP5YOGhap

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 18, 2014

It smells, it’s dirty.

It’s too polluted to filter and drink, according to a federal official.

The river I loved was gone.

Yet, people like Chris White, who told me about the “water master,” described the system to me as “genius.” It has to be that way, he says. These pipes and canals created jobs -- helped bring water from the wet part of the state down here.

And I kayaked one day with a farmer who told me we were “floating on food.”

The old me -- the me who couldn’t tell an egret from a heron -- might have bought that argument. The Central Valley supports a large chunk of a state with a $42.6 billion agricultural economy. But now that I know this river -- know what beauty and music it’s capable of creating -- know that the fish used to be so thick you could run across them -- I can’t imagine how a person would see the engineered murder of a river as “genius.” I see it as a tragedy that needs to be righted.

I wanted to get out of this place where the ground is sinking, a river disappearing.

Where no one and everyone is to blame.

But I knew it only would get worse from there.

I was approaching the desert stretch.

Forty miles.

And almost no water.

I left the kayak in a parking lot and started walking.

I had no idea what I’d find ahead of me, and those I’d sought out for advice weren’t much help, either. No one seemed to know what the dry section would look like, or where it would end. They did know where it began: here at Sack Dam, a rickety, partly wooden structure that diverts the totality of the San Joaquin, leaving only a trickle of water.

Not sure if this is the end of the line? #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/wlX0huz6ni

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 19, 2014

The water goes to farmers with “senior” water rights, including descendants of rancher Henry Miller, who helped settle this area in the 1800s. There’s a certain aspect of California water that operates like an elementary school playground.

It’s finders keepers.

Losers?

Well, you know.

(Nerd note: California’s water law fuses a few different systems. The state adjudicates water rights that were claimed after 1914. That’s when California started being a little less Wild West and a little more lawful. People who own land on the riverfront also can claim “riparian” rights to the water in the river.)

I expected this part of the San Joaquin -- the dry part; the “dragon on the map” as one woman put it -- to be where I’d find the people who most desperately want a river back. It’s on their land, after all. I wouldn't see until later how wrong that was.

For now, I felt lucky to have a companion on my walk:

We are off! Walking the #endangeredriver where it's dry. W @riverkatz from @riversforchange pic.twitter.com/sfQrZt77Kh

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

That’s Danielle Katz, a river nut since she was four months old, when her dad took her paddling on the Stanislaus River, a tributary of the San Joaquin. Now 33, she started a non-profit called Rivers for Change, which aims to use source-to-sea river trips for educational purposes. She tried to make a trip down the San Joaquin in 2012 and failed because it was too dry. She heard about my expedition and told me she’d walk the dry section of the river with me. It interested her in part because it’s so mysterious.

We walked maybe 1½ miles past Sack Dam, following a levy, wobbly silhouettes of farmworkers off in the distance, before we came to this:

This is where the water ends. Wow. Crazy to be standing here. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/T4FZYyIj0s

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

I heard a great blue heron barking in the distance -- its mournful call sounding almost primordial. Its distress echoed beneath a radiator sun.

#endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/GUYQojwu1D

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

This is so crazy #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/pqBLncvhi5

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

The river has turned into a beach -- a place so un-river-y that there are footprints and tire tracks. It’s been dry since the 1960s. Some people use it as a road; others farm in what could be considered part of the now-dry riverbed. At the edge of the sand, I stood on top of the cracked earth. The pieces of dried-up clay wiggled beneath my feet like loose teeth. I saw a dead crustacean on this moonscape.

Former reaident. Cicadas sound like tinnitus. Willow seeds hitting my face like snow. Sun is SO HOT #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/PBDeBjjWRy

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

And shotgun shells on the dirt.

Please don't be foreshadowing.... Still walking along #endangeredriver and it still has some water in it. Weird .. pic.twitter.com/YqFGANldLD

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

It was hard to believe it had come to this: Where is the cool, clean water from the snow-covered peaks, water so pure that backpackers have been known to drink it without treatment? Absolutely none of that water is left. And the obvious question -- where did it go? -- is answered oh-so easily when you’re standing in a place like this.

Look around at the edge of the river-beach.

You’ll see the emerald-green farms.

Welp. Someone's gots the water. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/O7LtWlPEmw

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

I decided to hatch a mini-protest.

I pulled a rubber ducky out of Danielle’s backpack (she carries it with her on all her “river” trips), tied it to a string, and dragged it across the nonexistent river.

This was my form of “pleasure boating.”

Dragging this little watercraft across the dry riverbed to prove navigability. That work @agleader? :) cc @riverkatz pic.twitter.com/gMccxEnSMi

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 20, 2014

It’s goofy, I know.

But maybe it would help prove this river is still navigable.

Still alive.

And, in some small way, still worth saving.

Danielle and I stopped for a brief lunch, and soon reality set in: We’d be trudging, through thigh-burning beach sand, for days, under a relentless sun, with virtually no shade. By midafternoon of Day 1, I was completely covered in sweat. Salt lines formed around my elbows and on my chest. I tied a bandanna underneath my hat just to keep the rays off my neck and the saltwater from dripping into my eyes.

It was that light-headed, nearly hallucinating kind of heat -- the kind so tangible it wiggles the horizon. It was absolutely miserable, but I thought of the farmworkers I met in Mendota, imagined them picking melons under this same sun. I felt awful for fixating on my own woes -- the pack digging into my right hip like a knife.

The #endangeredriver would be a sexy bastard in this channel if it had water. Quick turns. Narrow. (I'm losing it) pic.twitter.com/aC6BvCBqfL

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014

Then I noticed a legitimate gripe, no matter the circumstance.

We were running out of water.

It was my fault, of course.

I probably made the water too easy to drink -- hanging a hose from the 3-liter “bladder” of water in my backpack over my shoulder, near my mouth.

All I had to do was move my head a few inches to take a sip.

So I drank -- and drank and drank.

I could feel the pack getting lighter, knew the reservoir was emptying.

I couldn't help it, it was hot, and I was freaking thirsty.

I didn’t worry about it too much at first -- since I knew we had a large jug of water waiting for us near our projected campsite, 10 miles from the start.

But mile after mile of trudging through ankle-deep sand is just as hard as it sounds to anyone who’s tried to run on a beach. Each step takes about 17 times the energy you think it should, all of your effort absorbed by the granular surface.

This feels like a stair master in hell pic.twitter.com/QmL2ksdrC0

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014

I really noticed how tired I was -- and how fast I was downing all my water -- when Danielle stopped near the Highway 152 bridge, which crosses the dry river, and is labeled with a neat, green government sign -- to recharge in the shade.

So strange and kinda great that from the river's perspective you can't see the cars. From above, u never see rivers pic.twitter.com/qGnAAM9RGZ

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014

My feet were throbbing -- Danielle’s were covered in blisters -- and, even though I was wearing long pants, my legs were completely caked in dust.

Taking a break. This is sooo much harder than I expected. Gross feet. Been about 7/8 mi dry so far #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/BBkl1UZsMj

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014

I knew I had to keep going forward for the people following this journey -- and for Walt Shubin, the farmer who was counting on me to finish. How crushed he would be to see, as I was, a once-vibrant river drained and forgotten. It’s almost unthinkable that the second longest river in California could be intentionally killed -- left as a desert in a little-traveled part of the Central Valley. I had to think that perhaps more people would be outraged (is anyone but me outraged?) by the death of the San Joaquin if the dry riverbed were more visible.

We trudged on, but the reality remained: It was 6 p.m. and we hadn’t made it halfway to the campsite. Soon, the sun was setting overhead, turning the sky a haunting purple. Danielle walked ahead of me at this point, so far I couldn’t see her. And I didn’t have the cell service to be able to call if I’d needed to find her. I heard owls hooting at dusk, saw a raccoon that was following me along the path.

There was a surreal and beautiful quality about the scene.

Still, I was anxious.

Where were we going, exactly? And did we have the water to get there?

I walked up on a levee to get a better view of the surroundings. Each step up there, on the firm ground, as opposed to the dusty riverbed, felt like a leap forward. I didn’t want to cheat by walking up there, but it was nearly dark, and I wanted to get my bearings. During the 30 minutes or so I spent up on the levee I saw a tractor driving by. I thought of the warnings I’d received about the hostility of the landowners in this area -- and the shotgun shells I’d seen in the river. I briefly considered hopping behind some shrubbery to hide. But it was dark enough that I decided instead to do what the animals do: stand still and wait for it to pass.

The tractor was dragging a ghost-like smoke behind it. A cloud hung over the field, suspended in time. There was no wind to move it, and I wondered what it was.

The air tasted like Sudafed tablets, and I hurried past.

Danielle and I made it to our campsite, on the edge of a green plot of tomato plants, by 10 p.m., thirsty and starved. We’d left a jug of water out here in advance, thank God. We each chugged a bottle-full and then used it to make macaroni and cheese on my small camping stove.

Danielle takes on the river’s problems as her own, and she’ll do anything possible to try to avoid letting her presence harm the river. So, when we’d finished eating, she asked me to do something I thought was completely bonkers: She told me that when I washed the cheese-coated pot out with water, by hand, that I should drink the cheesy dishwater instead of pouring it on the ground.

She didn’t want it to contaminate the river, even though there’s no discernible river here. Even though we were camping on the edge of a fertilized, irrigated farm. I complained about this loudly for maybe 10 minutes before just doing it.

To me, it had started to seem like there wasn’t a river here to protect.

The next morning, I started shuffling around, per usual: squishing my sleeping pad into its storable, cylindrical shape; snapping my tentpoles into neat bundles, like fiberglass firewood kindling; pouring just exactly the right amount of water into a lightweight pot and then boiling it for lumpy, not-too-wet oatmeal and a little coffee.

I even drank the oatmeal water -- bluh -- to placate Danielle.

That’s when Danielle told me we’d had an overnight visitor: A tractor, which had left a noticeable trail of a powdery yellow chemical all around our campsite.

We’d been fertilized.

Danielle had heard the tractor spraying a nearby field and, consequently, us, between the hours of midnight and 1 a.m. I later would learn that farming is such an intense industry out here that, during planting and harvest, someone is working somewhere on these farms at every hour of the day and night. What I never learned is the exact composition of that chemical. It could have been fertilizer, one man told me; or sulfur, which farmers spray on crops to keep them from getting “sunburned.”

I was so exhausted, and so fully asleep, I hadn’t noticed.

It wasn’t long until we had another visitor.

Chase is walking with me this morning, explaining where post-river water goes to and comes from #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/gCF55enIH1

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014

That’s Chase Hurley, who runs the local irrigation district, which is responsible for moving water from the former riverbed onto the fields of these nearby farmers.

He was sent here, essentially, to stop us from following the river.

That’s being a little blunt, perhaps. I talked with a farmer in the area, Cannon Michael, who told me I couldn’t walk along the river the entire way -- that some landowners, he said, didn’t want me “on their land,” meaning, more or less, on the river or along its former banks.

He’d called Chase and asked him to accompany me. I didn’t object to this, since I thought it would be nice to have a guide. But I didn’t intend to back down from my plan to follow the riverbed.

I asked if I’d be trespassing.

“Well, that’s a good question,” Chase said.

Those locals “own it to the bottom.”

That can’t be true, can it? Rivers are held in the public trust -- a resource for everyone. But what if the river’s dry and has been for decades? Does that let someone own it? What if that person is also the someone who helped dry it up?

I didn’t want to back down. Then I realized I had to. A few miles down the path, the riverbed started to fill with pesticide-laden pools of agricultural drain-water.

It wouldn't be possible to walk through them. I couldn’t make it through the contested land without having to “trespass” by stepping out of the riverbed.

Wider view. The San Joaquin has water intermittently here. But it comes from farms, with fertilizer pesticides etc. pic.twitter.com/a12ZH0QQ70

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014Water almost looks like a solid surface. Like you could walk on it even if you're not Jesus. AstroTurf color. Paint bucket, scrap metal/wood

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 21, 2014

So I took Chase’s advice and caught a ride in a car around a mile or two of the river where Chase and Cannon said the landowners wouldn’t let us walk. (I wasn’t able to get them to comment on the record).

The general sentiment in the area seems to be that the river restoration plan is a waste of money, could ruin useful farmland -- and could flood homes that are located on or near the banks of the river.

“It’s going to spoil a lot of ground” if water returns to the San Joaquin, said Tom Gage, a pest control adviser I met in the area.

"Well I hope this is going to be a two sided story." Dog's name is Elka. He's out looking for bugs #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/5Zr3G1KXNI

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 22, 2014

In a drought, these are farmers who don’t want water. They have enough of it -- piped in from somewhere else. They’d rather the river remained empty.

I started to wonder if they were right. Maybe this is the river we sacrificed.

The one we killed -- that we farmed to death -- so that others can live.

State Highway 165.

That’s where I planned to put my kayak back in the water, not realizing that the worst, by far, was yet to come.

River's back! Loading up boats after walking for three days down the dry bed of the San Joaquin. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/2QjnkdwAQU

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

Danielle helped me drive my boat to the spot where that highway crosses the San Joaquin, just inside the boundary of the wildlife refuge system. I crawled under the bridge, to a spot where clearly people had been living, or at least spending a good amount of time -- food wrappers and remnants of campfires in the dust.

The river looked like a river again, amazingly.

Man, loading this beast is half the battle. Heading out. Hoping to meet a farmer downstream. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/FqqBvxUnPh

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

I waved goodbye to Danielle -- gave her a hug and thanked her for helping me get through the dry section -- and set off on the water alone.

It felt euphoric to be back on the river -- actually floating!

But that didn’t last long.

The San Joaquin was sputtering back to life too slowly to carry the boat.

Without water, I had to lug the boat across mud fields and over beaver dams.

Nature does dams too. They are just sliiiightly smaller than the ones I saw upstream. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/OMyQpg6Qe9

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

Eating lunch and thinking this over. Hoping some more water magically appears. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/3Nthu6ESMf

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

Still dragging the boat through mucky water that looks like cake batter. See a clearing, thank god. #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/6xkmtWcoH8

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

I pulled the boat with a parachute cord that Tom -- the insurance guy and bird lover who paddled with me a week before -- tied up for me.

Without that, I would have been a goner.

I hoisted the 100-pound boat over three beaver dams and finally came to a clearing. Amazing! I thought. Maybe the water would pick up from there.

Instead, I found the quicksand.

And the river flowing backward.

The Barry White mud, remember?

I was stuck up to my knees.

River is flowing backwards here. This is just exhausting. Dumped gear. Still lugging boat #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/rsQBfA14JL

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

Exhibit a pic.twitter.com/SJnBQqss6f

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 23, 2014

I panicked. Bubbles of air started rising through the mud like Champagne as my leg sank deeper. I could feel the mud grabbing onto my limbs, vacuum-sucking them. It felt like I was tied up in plastic wrap, then plaster mold. I tried high stepping, I tried twist-wiggling, I tried shuffling forward, leaning back -- nothing worked.

Then it hit me: the kayak!!

It was within reach, thanks to the string Tom had tied for me.

I grabbed the loop and pulled it close.

Probably 20 minutes later, I’d successfully used it to ratchet myself out of the mud -- hoisting myself up with my arms, like a flabby-armed gymnast on the pommel horse.

It was a sweaty, panicked, maddening experience.

And before you think I’m exaggerating, know that I later met a fish biologist, Lenny Grimaldo, who told me the same thing happened to him.

And he dislocated his hip trying to escape.

I got stuck several more times -- all told spending at least an hour sticking and unsticking myself from the quicksand. Then there was the business of what to do once I was unstuck. Ever so cautiously, one step at a time, I made my way to the dry “bank” of the river. I couldn’t drag my 100-pound kayak across the land, much less carry it, so I decided to unload all my food and gear.

I left it behind, dragged the empty kayak forward, and then went back for the gear.

Wash, rinse, repeat.

It was absolutely exhausting. I counted my steps to try to take my mind off the misery -- “58, 59, 60 …” I tried to make it to 100 before giving myself a break, but often couldn’t. I wondered how I’d ever get out of this situation -- how I’d ever reach the sea. I was falling so far behind my daily mileage goal I couldn’t bear to think of it.

I thought about giving up right there in the mud field.

But there really wasn’t any way off this river.

There were steep banks on both sides.

Nowhere to go but forward.

I trudged on, stopping for the day at about 8:30 p.m. I set up camp along the still-muddy river, which was stagnant, but now really flowing.

I'm alive. Set up camp/ cooking noodles. Loooong day. By far the hardest so far, dragging the boat #endangeredriver pic.twitter.com/CkyAowtQFn

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 24, 2014

Frogs out here sound like busted cellos. But these coyotes ... Kinda freaking me out. Like RIGHT across river from sound of it.

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 24, 2014

The howls of nearby coyotes kept me up in a panic.

The next day, I would meet the man who makes the river flow backward.

I like this guy's spunk. "You won't make it to the Bay..you'd better be one f'ing good paddler" I have my doubts too! pic.twitter.com/tp4sfUG45u

— John D. Sutter (@jdsutter) June 24, 2014

In addition to telling me that, yes, his water pump on the river is what’s making it flow backward in the spot where I got stuck in the mud, he also offered this little bit of inspiration: “You won't make it to the bay.” I’d have to be “one f---ing good paddler” to do that, he said, and apparently I didn’t look like one.

(This doesn’t make him mean so much as observant, I guess).

The particulars on this little ray of sunshine: His name is Bob Kelley. “My great-great grandfather, and his father, arrived where we are today in 1852. They stepped off of a river boat” that had come up the San Joaquin River.

I don’t need to remind you how impossible that is now.

I wanted to hate Bob -- I really did.

I mean, he told me I’m on an impossible quest. And the water he’s sucking directly out of the river -- 10,000 acre-feet in total per year, he told me, out of eight pumps -- for use on his family’s land should have kept me from getting trapped in quicksand. He’s playing a small part in making sure boats and fish can’t traverse the San Joaquin -- that this part of the river remains mysterious and impassible.

But he was also so accommodating. Kind, almost.

After I spent maybe 30 minutes dragging my boat up to a tree and locking it to a branch with a lock that normally goes on my bicycle, he picked me up at a boat ramp near my coyote-laden campsite. His black GMC Denali truck has stair-step things that drop down automatically, and his car stereo was playing Billie Holiday.

How can you hate a farmer who plays Billie Holiday?

But, anyway, back to business.

Here are Bob’s thoughts on the river:

1. Salmon won’t make it here. They’d expect to stick their thumbs out and hitchhike since that’s the treatment they’ve been given to date by the enviros.

2. His water rights are great, but so what? Look at your history. “That water was created (emphasis mine, but wow) as a result of federal and state projects,” he said referring to the scarce, expensive water that is given (or not, this year) to farmers in other parts of the valley. “Our ancestors developed their water as a result of their own investment.” Well, is that fair today? I mean, you didn’t build those dams. “By nature, it’s going to make some people happier than other people.” Count him among the happy bunch.

3. On his connection to the land and water: “I’ve walked every inch of this ranch -- many times. … Every morning, I’m out walking a different part of the ranch.” Favorite animal? The river otter, which he’s only seen a few times. “All the animals out here, they’re survivors, they’re interesting to me. Even if I have to kill ‘em, like a coyote or a beaver … I still respect ‘em.”

4. On the fact that he’s making the river go backward and that I got really, really truly stuck in it -- almost hip-dislocatingly stuck? He wasn’t so much apologetic as practical. “We’ve gotta go out there and locate the beaver dams and trap the beavers so we can keep the water flowing to the pumps.” He later asked me to point to a map on his iPad to show him where the beavers were living. I felt like an evil accomplice in that moment, but it was a trade-off: He did drive me into town because I was out of sunscreen.

I didn’t have a hard time sympathizing with him.

He’s putting the river to work, dammit.

And maybe that’s the way it’s gotta be.

The gurgling, backward-flowing mess of a river had eaten days off my itinerary and worn my patience thin. I was mad at the river, mad at the conflict it creates.

I’d survived but had completely forgotten about Walt, the spirit of the river.

I went into survival mode -- trying to do anything I could to make up time. I just wanted to catch back up to my schedule and get off the water. Efficient, done. My hands were covered in calluses and one blister that looked like the red spot on Jupiter. My head hurt, my feet were tired, and all my clothes were covered in mud.