Story highlights

Minnesota football coach retires in emotional news conference

Coach Jerry Kill has suffered from epilepsy the last decade

His legacy extends beyond football: helping kids with epilepsy

The football coach wept at the podium. He stopped every few words, sought to compose himself and then choked up more. His livelihood, his passion, his dream ripped away.

The state of Minnesota came to a pause. So did everyone within the epilepsy community.

“Last night, when I walked off the practice field,” said University of Minnesota football coach Jerry Kill, “I feel like a part of me died.”

It was, perhaps, the most gut-wrenching retirement announcement in sports. Kill has suffered from a seizure disorder for the last decade. He’d managed to keep the seizures in check the last two years, but his seizures recently returned. His retirement was immediate and unexpected.

“This is not the way I wanted to go out,” he said. “This is the toughest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

I clung to his words, felt his agony and fought back tears right along with him.

Because the coach helped save my son.

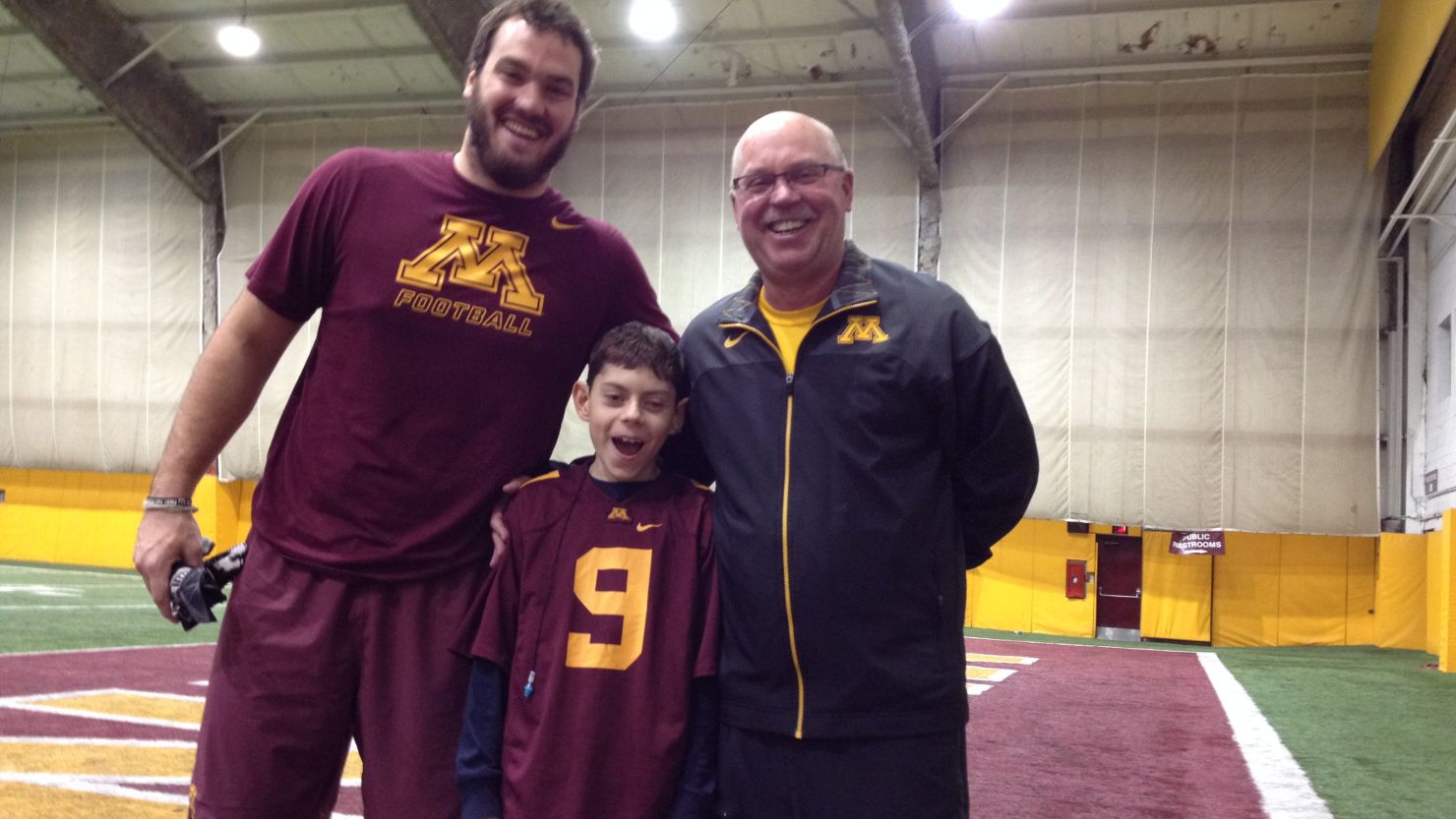

I profiled Kill last year for CNN.com in a piece called “Grit Beyond the Game.” The story delved into Kill’s courage off the field and how he has inspired people with epilepsy everywhere, including my son, Billy, then 11.

Kill’s generosity with children suffering from seizures was well known within the tight-knit epilepsy community. Got a kid with epilepsy? He’d hand out his personal cell phone number. “Call any time,” he’d say in his Midwestern twang.

When the Minnesota Twins asked him to throw the first pitch at a ball game, Kill declined. Instead, he gave the honor to a teenager with epilepsy. He hosted annual games dedicated to epilepsy awareness the past three seasons, allowing children with seizures and their families to attend. Medics were on hand to help anyone in case they seized.

Kill formed the Chasing Dreams fund to help with seizure-smart school initiatives across the state, and he hosted a summer camp for children with epilepsy.

My son had never met anyone who had seizures; he started referring to Coach Kill as a part of our family.

Billy and I flew up to attend the Gophers’ epilepsy awareness game against Ohio State last year. When he and Kill met, it was like they’d always been friends. Coach hugged him and joked about Billy’s thick head of hair: “You got hair, I don’t.”

Billy reached up and rubbed Kill’s golden dome. Coach handed him a signed football helmet. “You’re my idol,” Kill wrote.

At the following week’s news conference, Kill joked with reporters about how Billy put him in a better mood. “The youngster, full of energy,” he said, “I mean funny.” The coach added, “He did a lot for me.”

What Division I coach takes the time to say something like that while being quizzed about a loss?

Coach Kill did a lot for my son – beyond just giving him hope and a helmet.

A neurologist in Memphis saw a YouTube clip from Billy’s visit with Kill.

The doctor said he thought he could help my son. In late December, Billy underwent surgery to have the brain equivalent of a pacemaker installed. The surgery has been life-altering. My son has gone from having three or four seizures a day to about one a month.

Our family now advocates for people with seizures.

Many will remember Kill’s career for his on-field accomplishments. He took a perennial Big 10 doormat and turned the Golden Gophers into a viable program.

Former Gopher Cedric Thompson Jr., now a safety for the Miami Dolphins, tweeted to Kill: “Coaching or not, I know you will continue touching lives!”

So true.

Minnesotans used words like “genuine,” “integrity,” “fighter,” “authentic” to honor Kill on a popular message board.

I’d add another: Inspiration. Especially to children with epilepsy.

In my case, had it not been for Kill’s generosity, my son wouldn’t have gotten the care he needed. That’s something I witness daily, every time my son smiles instead of seizes.

As he struggled for words at his news conference Wednesday, Kill pondered what’s next after 32 years of coaching: “I ain’t done anything else.”

He then referred to his Chasing Dreams fund and paused, almost lost in thought of the kids he’s helped. “I’ve got to get better,” he said.

That’s something everyone is rooting for. We’re right there with you, Coach.