Story highlights

Scientists examine ancient horse dung to determine Hannibal's route through the Alps

Great Carthaginian general led thousands over mountains to attack Roman Republic from north

Amazing what you can learn from horse manure.

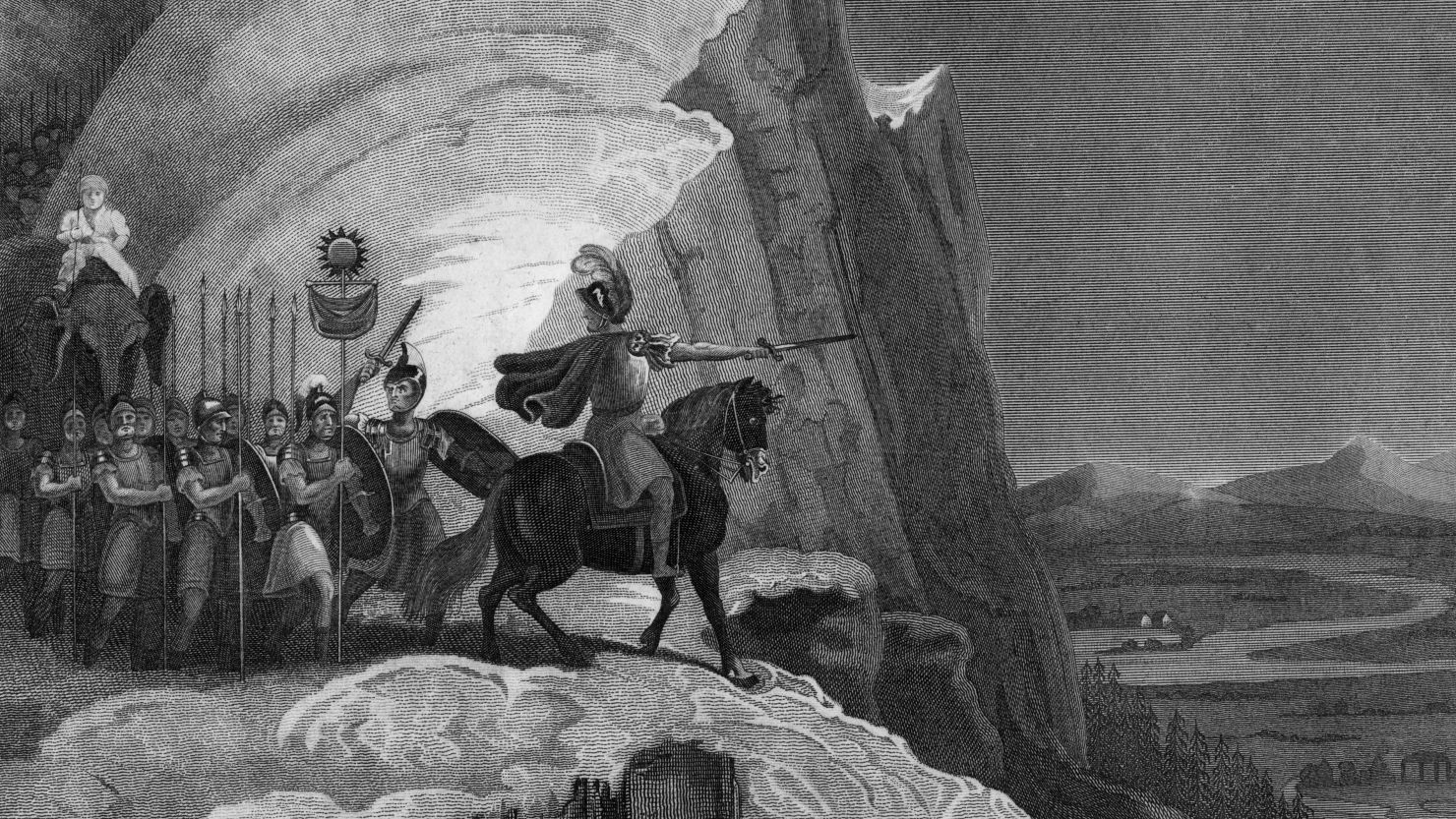

In 218 B.C., the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca led an army of more than 30,000 men, 15,000 horses and mules and – famously – about 40 elephants northeast through Europe and crossed the Alps to attack the Roman Republic from the north.

It’s considered one of the great achievements in military history.

But what was Hannibal’s precise route? For centuries, historians have debated the question.

Now, Chris Allen, a microbiologist at Queen’s University Belfast, thinks a research group has solved the puzzle – thanks to “modern science and a bit of ancient horse poo,” he writes in a blog post.

Allen and a team led by Bill Mahaney of Toronto’s York University believe that Hannibal and his troops crossed the Alps at Col de Traversette, on the border of France and Italy southeast of Grenoble.

The surrounding terrain is incredibly rugged; even 22 centuries later, Google Maps recommends that a traveler from France cross into Italy and double back to arrive at the pass, though some single-lane roads in France will get you close.

Allen and the team “unveiled a mass animal deposition of fecal materials – probably from horses – at a site near the Col de Traversette,” Allen writes. Thanks to carbon isotope analysis, the group dated the dung to about 200 B.C. Descriptions of the area in historical writings also fit.

The UK’s Guardian notes that discussion about the route dates to the ancient historians Livy and Polybius. The Col de Traversette was one of many paths considered, but its narrowness and height – it’s close to 10,000 feet above sea level – made it daunting.

Allen believes that Hannibal may have taken the dangerous route because of his fear not of the Romans but of tribes that lived in the region.

He cautions that the group’s research is not complete. Gene analysis needs to be expanded, he writes, and he’s hoping researchers discover parasite eggs preserved in the mire.

“With more genetic information we can be more precise about the source and perhaps even the geographical origin of some of these ancient beasts by comparison with other microbiology research studies,” he writes.

Hannibal’s travels were not without fatalities. Accounts differ, but it’s generally believed that he lost more than 10,000 men and possibly many more. Moreover, all but one of his elephants died.

However, his success led to his greatest victory, at Cannae in 216 B.C. The Second Punic War between Rome and Carthage raged on until 202 B.C., when Hannibal was defeated at the Battle of Zama.

The findings of the international team of researchers are published in the journal Archaeometry.