Like baseball great Jackie Robinson he was a sporting pioneer. Except, unlike Robinson, his story is largely unknown.

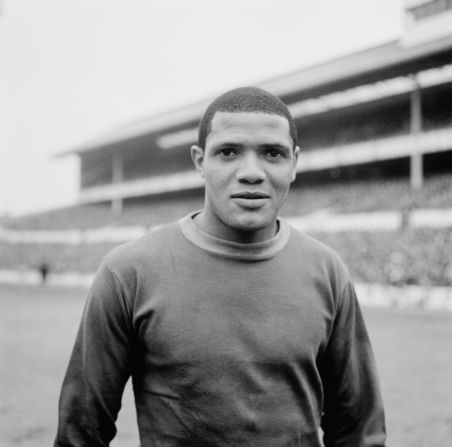

When Albert Johanneson walked onto the pristine Wembley turf in the 1965 FA Cup final he became the first black player to ever appear at one of English football’s showpiece events.

In the 84th edition of the FA Cup final, Johanneson’s presence was seen as a watershed moment – the man who left Apartheid South Africa to better himself and in turn became a pioneer.

On Saturday, at this season’s final between Aston Villa and Arsenal, his life and contribution will be honored not only by English football – but by those who carry him in their hearts.

“My husband says he puts my father and Jackie Robinson in the same league,” Alicia, Johanneson’s youngest daughter, told CNN, referring to the baseball star becoming the first African American to play Major League Baseball.

“My husband sees my father, like Jackie, as leaving an indelible mark on history by blazing a new trail in the sport of football for others to follow.”

The English Football Association has flown Johanneson’s eldest daughter Yvonne and her two children Stephanie and Samantha, from Atlanta, Georgia, to watch this year’s final from the Royal Box alongside heir to the British throne Prince William.

A short film will be shown on the two big screens inside the stadium where the crowd will be able to watch Johanneson in action.

On May 1 1965, Johanneson, lined up for Leeds United against Liverpool, shook hands with Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh – the British Queen’s husband – before trotting away to play in the biggest game of his career.

“On the day of the final I was actually cheering for Liverpool to win, but only because I was in love with the color red at that time,” Yvonne told CNN.

Yvonne was not to be disappointed – Liverpool triumphed 2-1 as Johanneson’s attempt at winning the FA Cup fell flat.

But his appearance in that game was the crowning moment of a career which owed much to a man’s determination to succeed despite the racism and discrimination which plagued his early life.

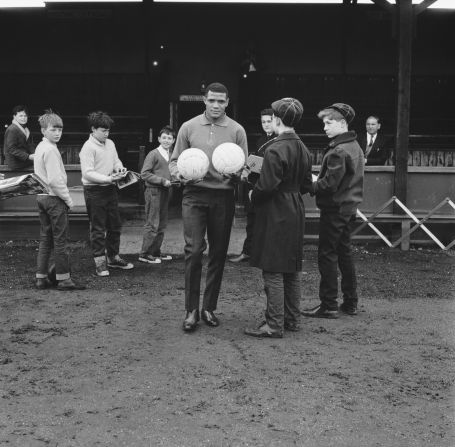

Nicknamed “The Black Flash,” because of his rapid pace, Johanneson grew up in Johannesburg at the time of great oppression during the Apartheid era.

It was his football skills which would eventually allow him to escape the country and move to England, where his talent was spotted by a former school teacher, Barney Gaffney, who tipped Leeds off that he had found a star in the making.

Leeds had already signed Gerry Francis, also a black South African, and manager Don Revie offered Johanneson a three-month trial.

It did not take long for Revie to realize he had discovered a gem of a player.

“Signing Johanneson was a real statement by Revie,” Phil Vasili, author and historian told CNN.

“Revie was a young manager at the time and he wanted to transform Leeds.

“They were a Second Division side at the time and bringing Albert into the squad showed his intentions to revolutionize the club.”

Johanneson made his debut for Leeds in 1961, setting up one of his side’s goals in a 2-2 home draw with Swansea.

Life in England was a challenge – the barriers which prevented him sharing the same tables as his white teammates or the same bath were no longer there, but there were times he struggled to deal with his new found freedom.

He had to grapple with the notion that he would be able to sit at the front of restaurants, or that a white apprentice would clean his boots – though on the pitch he was in fine form, particularly during the successful promotion season of 1963-64.

His pace and trickery caused constant problems for defenders, while his own teammates were often in awe of Johanneson’s ability to beat his man.

That season Johanneson scored 15 goals from the wing as Leeds won the title and reached the First Division.

But life would become more difficult in the top-flight, despite the club reaching the FA Cup final, as he had endure racist chanting and the hurling of bananas.

“My mother said that she always found it odd that he never wanted her to come and see him play,” Yvonne said.

“Now she has a better understanding of why that could have been. It now appears obvious that he wanted to protect her from hearing the racial slurs being hurled at him and similarly safeguard her from being the brunt of such ignorance.”

During a game with Everton, Johanneson complained to his manager Revie, that a member of the opposition had called him a “black b*****d.” The response which came back from Revie was, “well, call him a white b*****d then.”

“From what people have told us, we understand that there were some people who were incapable of separating the color of his skin from how well he could play the game of football,” said Alicia.

“They, therefore, considered him to be inferior no matter what, and consequently fair game for their abuse and disdain.

“Much of the racism we learned of him having had experienced apparently came from the verbal abuse from fans and some of the players on other teams.

“He may have experienced other forms of racism, but he wasn’t one to talk openly about what he went through with us.

“I mean, we were children after all. I think the prejudice he experienced was something he didn’t want us to know about since it wasn’t directly touching our lives.

“Now that I know what I know, I think it took quite a bit of courage for him to shield his family from seeing that uglier side of the world too soon.”

The legendary Manchester United winger George Best once said that “Albert was quite a brave man to actually go on the pitch in the first place.”

But while he might have struggled on the field, particularly after the FA Cup final defeat where he endured a series of nagging injuries, his daughters recall a musical loving father who owned an extensive collection of country and western albums, as well as reggae and old standard classics.

He would watch “Top of the Pops” a weekly music show on television and would love watching his children dance to whichever guests were playing.

There were the family outings to the cinema whenever a new Disney movie came out or they would take long drives into the Yorkshire countryside in his beloved Rover 2000 with the picturesque York and Harrogate two of the favored destinations.

“He was a real foodie, as they say now,” said Yvonne. “He loved his mixed grill, curries, steak dinners and Chinese food.”

Johanneson, and his wife Norma, who is now 73, would regularly attend their children’s sports days with a picnic nearly always on the agenda.

“My father really liked Coke, he drank it every morning instead of coffee or tea,” Yvonne said.

“I was quite athletic when I was younger and would pretty much always win my races. However, there was one time when I came a close second and I can remember my Dad cheering me on like crazy because it was a close race between me and another girl.

“He could have been really upset with me at the end of that race, but I remember that he wasn’t at all. He knew that I had tried my best and he was cool with that.”

However, Johanneson was also fighting alcoholism – and it eventually took over his life.

The trials and tribulations of Johanneson’s life have been documented in several books, although according to at least one of his daughters, they have focused more heavily on his declining years and battle with alcohol than his contribution on the football field.

“I would never want to negate the fact that my father struggled mightily because of his addiction to alcohol, but that wasn’t the sum total of who he was by any means,” Alicia said.

“I also think there’s been an unfair tendency to portray him as a congenitally weak individual, ‘poor Albert’ – the guy who had no confidence and therefore couldn’t cut it in the big leagues of what was then First Division football.”

Johanneson stayed at Leeds until 1970, though he struggled with fitness and loss of form, before eventually agreeing a move to York City in the Fourth Division, where injury all but ended his career.

By 1974, Norma could no longer cope with her husband’s drinking and behavior, moving with the children to Jamaica and then onto the U.S.

Johanneson died in September 1995 at the age of 55.

“For anyone being brought up in the environment of Apartheid, life was difficult,” Vasili said.

“It was a heavy burden to carry and it damages people. It hurts people being treated as a second class citizen all your life.

“What he achieved was quite amazing but because he was a quiet and retiring type of guy, perhaps his story isn’t well known.

“Sometimes, these things take time to come the fore. Once the dust settles, it takes a while for people to realize his true significance and I think that is what happened.”

Johanneson’s achievements have not been forgotten at Leeds where he played 200 games and scored 68 goals.

The club has embraced his contribution and there are plans afoot to have a permanent reminder made of his contribution to the club and city.

Both daughters believe their father deserves his place in history alongside other pioneers such as Arthur Wharton, Andrew Watson and Walter Tull, all of whom helped pave the way for black football players in the United Kingdom.

His legacy, which will be remembered with particular fondness on the occasion of this year’s FA Cup final, is one both Yvonne and Alicia would like to echo around the world of football for years to come.

“As people we tend to be fixated on the concept of instant gratification,” Alicia said.

“We have a tendency to forget that it often times takes a very long arc of history to make changes occur and to see things in the fullness of the circumstances in which the change was wrought.

“For us, it makes sense to have people like my father who purely through his talents and love for the game of football became a face amongst many others who led the way for change in the sport and became a role model for other black people of the time.

“That’s pretty much how we would like him to be remembered, as a catalyst for societal change and for the joy he gave his fans.”

On Saturday, they will have that opportunity to remember their father – along with the rest of the football world. Albert Johanneson, 50 years on, never forgotten.