Editor’s Note: Aric Chen is Curator for Design and Architecture at M+, the new museum for visual culture being built in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District. He previously served as Creative Director of Beijing Design Week, helping to successfully relaunch that event in 2011 and 2012. Chen has also been a frequent contributor to publications including The New York Times, Monocle and Architectural Record.

A friend of mine, the fashion designer Masha Ma, has a succinct way of explaining the secret to getting things done in China: “Embrace the chaos.”

Those words also go a long way towards describing the strategy I relied on as the first Creative Director of Beijing Design Week, in 2011 and 2012.

Now running until October 7 in its fifth edition (sixth, if you count a pilot version in 2009), Beijing Design Week always had to be big, and by extension, complicated.

Small simply doesn’t make an impact in a city of 22 million people, much less a country of 1.4 billion. And so, covering anything from furniture, products, fashion and graphics to, especially, architecture, urbanism, craft and making, Beijing Design Week now comprises hundreds of exhibitions, pop-ups, talks and workshops spread annually across the capital city.

However, as with so many things in China, beneath the appearance of monolithic unity lies a more fragmented reality, a reality we wanted to exploit and embrace.

Beijing Design Week was, and remains, a government initiative, now under the auspices of the national Ministry of Culture and Municipal Government of Beijing.

It arose from a directive to bolster design and innovation as China, and local authorities, seeing the economic writing on the wall, jumped on the global creative industries bandwagon.

But is a top-down mandate—inevitably focused, in that top-down way, on official forums, forging diplomatic ties and, at Beijing Design Week, the pageantry of a flamboyant opening ceremony that has featured 3D projections, sky trackers and pop-music performances—enough to foster design in a meaningful way?

Bottom-up platform for designers

A government cannot, of course, whip up creativity the same way it can order the construction of an airport or bridge; it can only provide a better environment where people can thrive by developing, realizing and sharing their talents. (By the same token, you can’t promote economic development through the creative industries when your creative industries aren’t yet strong enough to compete.)

And so Beijing Design Week became an experiment in turning the government’s top-down support—whose importance should not be underestimated—into a bottom-up platform for the designers, makers, curators, companies and others who, we believed, should be put front and center, and in deeper engagement with a broader public.

This is certainly not a revolutionary concept; design weeks around the world, from London and Milan to New York and Tokyo, have long acted as incubators, launchpads and megaphones to one degree or another. But in these early years for design in China, the idea of decentralizing a centrally-directed effort felt both novel and urgent.

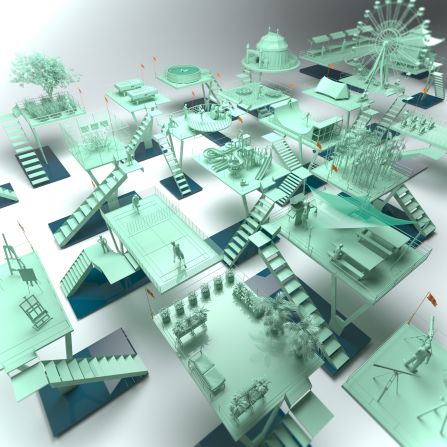

Accordingly, beginning with its relaunch in 2011, Beijing Design Week has expanded well beyond the functions and venues favored by officialdom to become an agglomeration of zones, sites and activities throughout the city—all under the umbrella of Beijing Design Week, but each with its own autonomy and growing self-sufficiency.

Under the energetic guidance of Beatrice Leanza, a longtime Beijinger who took over as Creative Director in 2013, this year’s Beijing Design Week presented case study houses for revitalizing the historic Baitasi neighborhood; the world’s largest 3D-printed structure (as certified by Guinness) at the Parkview Green complex; and craft collaborations, urban research labs and hackathons throughout. More and more, designers and others are taking the initiative themselves—and persevering.

In 2012, a group of creatives in the Caochangdi gallery district created their own Beijing Design Week zone and kept it going for three editions. This year, facing funding difficulties, the organizers secured the sponsorship of the nearby Indigo mall and brought their installations, exhibitions and programs there.

Meanwhile, bigger brands continue to gravitate towards the larger and more family-friendly spaces of the 751 former industrial complex, adjacent to the 798 arts district. Younger designers are drawn to the historic alleyway neighborhood of Dashilar.

It’s a sprawling, lively mix—sometimes overwhelming, often imperfect, but faithful to the original intention. Going beyond the pervasive tendency to put bureaucratic, economic and other agendas first, we wanted to simply offer the space, both figuratively and literally, for designers, their supporters and the public to do what they do.

Lasting impact for Beijing’s historic districts?

This is not to say that Beijing Design Week is aimless; in fact, it has arguably played a role already in shaping Beijing itself. In Dashilar, a uniquely layered historic district just south of Tiananmen Square, Beijing Design Week acted as a catalyst for re-envisioning an area that had seen better days and was threatened with the kind of “renovation” that had destroyed other historic precincts around it.

By bringing renewed attention to Dashilar in the form of pop-ups, exhibitions, and other projects including public seating and community space proposals (some implemented) and collaborations with local craftsmen, Beijing Design Week helped strengthen the case for a revitalization strategy that sees a future for the neighborhood that more sensitively respects its history, urban fabric and existing residents.

Five years on, it’s still too early to declare success and say that Dashilar has been “saved.” But Beijing Design Week—or, more importantly, its collaborators and participants—can surely claim to have at least slowed down the process of destruction, brought alternatives to the attention of decision-makers, and set Dashilar on a better path.

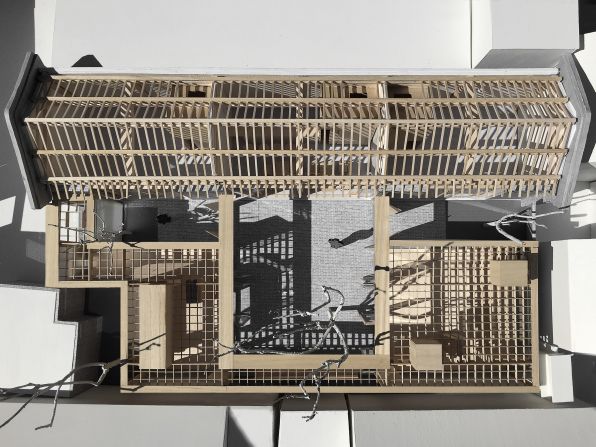

The implications may be broader yet: at the invitation of the area’s government-appointed overseer, this year’s Beijing Design Week launched another initiative in the historic Baitasi neighborhood that unveiled projects ranging from those case study houses, by prominent contemporary Chinese studios TAO Office, standardarchitecture and Vector Architects, to a free clinic for the elderly.

I have no doubt that Beijing Design Week has a significant future—in one form or another, which was exactly the point. We embraced the chaos: It was an event designed to have an openness and open-endedness that would allow it to evolve, respond to ever-changing conditions and survive and flourish on the strength of its range and diversity of stakeholders. One thing I can say for sure, with pride in so many people in Beijing, is that Beijing Design Week certainly doesn’t need me.