Story highlights

Timothy Tyrone Foster, an African-American 19-year-old, was sentenced to death in 1987 by an all-white jury for the murder of an elderly white woman

Foster's lawyers obtained the notes the prosecution team took while it was engaged in the process of picking a jury and say they reflect that the prosecution illegally took race into consideration as it struck every potential black juror

Several Supreme Court justices appeared sympathetic on Monday to claims from a death row inmate that new racially-charged evidence indicating prosecutors may have unlawfully attempted to remove African-Americans from serving on a jury should win him a new trial, nearly 30 years after his original conviction.

The case dates back to 1987 when Timothy Tyrone Foster, an African-American 19-year-old, was sentenced to death by an all-white jury for the murder of an elderly white woman. At the time, the lead prosecutor urged the jury to impose a death sentence to “deter other people out there in the projects.”

Nearly 20 years later – through an open records request – Foster’s lawyers obtained the notes the prosecution team took while it was engaged in the process of picking a jury. Foster’s lawyers, led by Stephen Bright, from the Southern Center for Human Rights, say the notes reflect that the prosecution illegally took race into consideration as it struck every potential black juror.

Justices on Monday grappled with the allegation that race discrimination persists in jury selection nearly three decades after the Court reaffirmed that jurors cannot be struck because of race. Some of the justices expressed skepticism of the notes and the justifications put forward by the State. But they also spent a significant time discussing a procedural issue that might block them from deciding the merits of the case.

On the merits, Justice Elena Kagan pointed to the notes and said to a lawyer for the state, “You have a lot of new information here from these files that suggests that what the prosecutors were doing was looking at the African-American prospective jurors as a group, that they had basically said, we don’t want any of these people.” She wondered if the evidence suggested a “kind of singling out” that would be the “very antitheses” of Court precedent.

“The prosecutors in this case came to court on the morning of jury selection determined to strike all the black prospective jurors,” Bright told the justices, adding that, “blacks were taken out of the picture here, they were taken and dealt with separately.”

He added: “We have an arsenal of smoking guns in this case.”

Foster was convicted for the murder of Queen Madge White, a 79-year-old retired elementary school teacher who lived alone. In court papers, the state said Foster “broke her jaw, coated her face with talcum powder, sexually molested her with a salad-dressing bottle and strangled her to death.”

Beth A. Burton, Georgia’s Deputy Attorney General told the justices that the prosecutors at the time anticipated that they would be challenged down the road, and that is why they highlighted information concerning black jurors. She added that prosecutors listed several race neutral reasons for the striking of jurors.

Justice Anthony Kennedy wondered how a Court should proceed when a prosecutor argues a “laundry list” of reasons for striking a black juror and some of those are “reasonable and some are implausible.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor focused on the research done by the prosecution team and whether it had only done “an extensive search on the blacks in the lists” and not some of the other prospective jurors.

The notes, released in court filings, are not color blind.

In 1987, as the legal teams were preparing to pick a jury, they were granted “peremptory challenges” that allowed them to dismiss potential jurors without explanation. But Supreme Court precedent – reaffirmed in 1986 – says, however, that jurors cannot be struck because of their race.

In the Foster case, the state and the defense used their peremptory strikes to reduce the pool to 12 jurors and four alternates. The state struck the four black potential jurors.

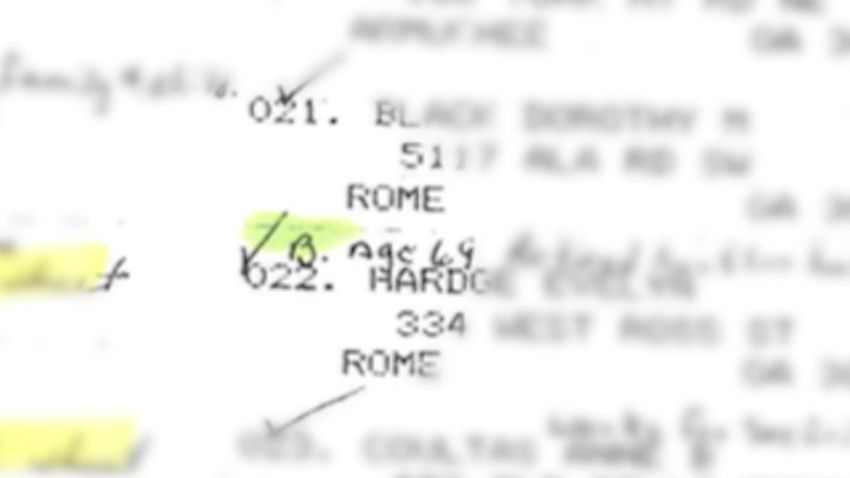

One set of documents from the prosecution files shows that potential jurors who were black had a “B” written by their name and their names highlighted with a green pen. On some juror questionnaire sheets, the juror’s race “black,” “color” or “negro” was circled. One juror, Eddie Hood, was labeled “B#1. Others were labeled B#2, and B#3.

Another set of the prosecution notes contains a coded key to identify race. There is a list of six “definite no’s” –the top five are black.

In Court the “definite no” list troubled Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: “Who was responsible for the definite no list?” she asked.

In 2013, a lower trial court conducted an examination of Foster’s claims and ruled against him.

Justifications for removing jurors

It was in 1986 in Batson v. Kentucky that the Supreme Court held that once a defendant has produced enough evidence to raise an inference that the state impermissibly excluded a juror based on race, the state must come forward with a race-neutral explanation for the exclusion.

According to Bright, the states’ race-neutral justifications don’t hold up. For example, the prosecution said one reason it struck a 34-year-old black woman was that she was near the age of Foster.

Justice Samuel Alito expressed concern about that stating that the woman was in her 30s. Foster, Alito said, “was 18 or 19.”

Foster is supported by former state and federal prosecutors, who say that prosecutorial misconduct was at play. The prosecutors argue in briefs that while some conduct across the country is “shockingly blatant” most discrimination occurs under the guise of purportedly “race neutral” justifications.

“The court’s decision in Foster will impact how easy it is for prosecutors to get away with excluding prospective jurors on the basis of race” said John Rappaport, an assistant professor of law at the University of Chicago Law School. He believes the court should rule in favor of Foster and emphasize that trial courts should not accept prosecutors’ implausible explanations for race-based strikes. Rappaport notes Justice Stephen Breyer has suggested abolishing peremptory strikes altogether.

In 2010, the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization that provides legal representation to prisoners, reviewed jury selection procedures of eight southern states and uncovered what it called “shocking evidence” of racial discrimination in jury selection in every state.

“In many cases, people of color not only have been illegally excluded but also denigrated and insulted with pretextual reasons intended to conceal racial bias,” the report concluded. The authors found that African-Americans had been excluded because they “appeared to have ‘low intelligence’; wore eyeglasses; were single, married, or separated; or were too old for jury service at age 43 or too young at 28.”