Story highlights

Greek Holocaust survivor Solomon Moshe spent his childhood hiding from the Nazis

Decades later, he finally had a bar mitzvah in Israel with other elderly survivors

Solomon Moshe never talked about his childhood. His memories were too painful, so he buried them.

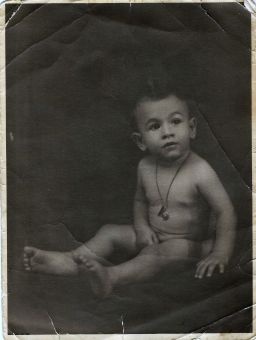

Moshe was born in 1937 in Athens, Greece. When he was four years old, Hitler’s army invaded his country.

Moshe and his mother moved every few months from one home to another, fleeing the Nazis. He was too young to understand why he was running, but he understood fear, and he saw that fear every day on the face of his mother.

He remembers having no friends as his family tried to avoid detection. Instead, he had his little brown teddy bear. It was, he says, his only company, and he treasured his bear.

Moshe and his mother survived the war, but many Greek Jews did not. Approximately 60,000 Greek Jews were murdered in the Holocaust – nearly 80% of the country’s Jewish population.

In 1956, Moshe and his family moved to Israel to create a new life from the remnants of the old one.

Like so many Holocaust survivors his age, Moshe never had a bar mitzvah, the Jewish rite of passage marking the transition to adulthood at 12 or 13 years old.

Holocaust survivors lost their youth much earlier. It was torn from them in concentration camps or as they fled the Nazis. They never had a chance to celebrate that important milestone.

Moved to tears

So earlier this week – just before Israel’s Holocaust Remembrance Day – a group of 50 Holocaust survivors, most in their 70s or 80s, drove from central Israel to Jerusalem.

They gathered at one of Judaism’s holiest sites, the Western Wall, crowding around a table covered in prayer books. Draped in prayer shawls and wearing religious skullcaps, they celebrated the bar mitzvahs they had missed so many years earlier. Solomon Moshe was among them, dressed in a suit for the special occasion.

“I am not embarrassed to say that I was moved to tears. Soldiers were saluting us like we were heroes,” he said.

Moshe stares off into the distance as he speaks, remembering the emotions that swept through him. He seems to be reliving the moment. And I suspect he will relive it many more times.

“After we finished, everyone had a spirit of harmony. Here we are, we have done it. We are here today more complete, and we feel that we got back what was missing,” he said.

READ: Dancing for Auschwitz’s “Angel of Death”

Treasure in a bag

Moshe spoke about his bar mitzvah experience in front of a small crowd in his hometown of Kfar Saba.

As he spoke, a small plastic bag sat by his right foot. He had kept the bag by his side all afternoon.

As he concluded his speech, he invited his grandson onto the stage and held the bag open for him.

Inside was the teddy bear from Moshe’s childhood. He held it up for the crowd to see.

Afterward, everyone gathered round to see the teddy bear, which his grandson named Yumbo. He invited the crowd to take pictures of the bear. If they forget his story, he told them, they will see the picture and remember once again.

I sit down to speak with Moshe after his presentation. I ask to see the bear.

As Moshe pulls it out of his bag, his voice cracks. It is the first time I have heard him holding back tears all afternoon.

Yumbo is now a faded brown. He is falling apart at the seams. Moshe holds him with the gentlest touch. He has cared for Yumbo for more than 70 years, and he’s not about to stop now.

“This bear,” he says, cradling it in his right arm as he might cradle a newborn baby, “we will show it to our children and we will tell them, ‘Yumbo was with your great-grandfather in the worst possible moments of the Jewish people.’ I will hold onto him until I go.”

Moshe already knows he will give his bear to his grandson. It is a way of passing on a story that is finally complete.