Story highlights

March organizers say they expect around 100,000 people to attend

Rally comes two weeks after a controversial electoral reform bill was voted down

Pro-democracy lawmakers hope a large turnout will pressure the government to reopen dialogue on political reform

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy lawmakers are hoping heightened political tensions in the city will draw a large turnout for the annual July 1 march and jump-start the stalled electoral reform bid.

July 1 marks the 18th anniversary of the city’s return to Chinese sovereignty from Britain in 1997, when it became a Special Administrative Region (SAR).

While the annual rally has always been about human rights and democracy, this year’s event comes at a crucial time. A Beijing-backed electoral reform bill was rejected by Hong Kong lawmakers last month, so democracy advocates hope a strong show of public support on the streets of the city could help to get their reform agenda back on the negotiating table.

The July 1 march organizer, Civil Human Rights Front group, is expecting this year’s rally to draw around 100,000 people – the biggest public gathering in the city since last year’s pro-democracy demonstrations brought parts of the city to a standstill.

“I think Hong Kong people’s determination to fight has not changed. We believe they will treasure this opportunity to express themselves and take part in the march,” Civil Human Rights Front convener Daisy Chan said.

READ: Hong Kong’s fight for democracy

Pro-democracy lawmakers, including Democratic Party founding chairman Martin Lee and Civic Party leader Alan Leong, have called on the public to come out and show their support, saying it will put pressure on the government to restart the electoral reform process.

But whether it will succeed in reigniting discussions and what kind of compromise could be reached given that Beijing is unlikely to relinquish its control over city elections remains unclear. Concerns over the fate of Hong Kong when its special autonomous status expires in 2047 are still looming large.

Political impasse

Although Beijing’s reform proposal allowed Hong Kong’s four million voters the right to select their leadership – known as universal suffrage – by 2017, opponents said the reality would be a sham democracy because all the candidates would be vetted by Beijing first.

“This is a fake democratic proposal,” legislator Albert Chan told CNN after the bill flopped.

“You wouldn’t be getting the people you want to vote for and this is a cheat.” Civic Party founding member Claudia Mo said.

Hong Kong is the only city in Chinese territory that enjoys a high degree of autonomy, including religious and press freedoms. However the city’s top official, or chief executive, is currently elected by a committee of 1,200 influential citizens and groups from the city, the majority of which represent big businesses and typically fall in line with Beijing’s views.

Anti-mainland China sentiment flaring

Tensions in the former British colony are not only political. While the city is still dealing with unresolved negative sentiment after last year’s “Occupy” protests, many residents are also bristling at the strain mainland Chinese visitors put on the city’s resources.

Last year, 47 million mainland Chinese visited Hong Kong according to government figures, easily dwarfing Hong Kong’s population of 7 million.

The competition from mainland Chinese for school spots and hospital beds, the overcrowding on the subway and a general sense of cultural invasion have left many Hong Kongers feeling marginalized, and spurred an anti-mainland Chinese ‘localist’ movement.

The government has tried several measures to ease the animosity. In 2013, it restricted travelers from bringing more than two tins of milk powder across the border–an effort to crack down on parallel traders catering to demand in mainland China for safe infant milk powder after a 2008 melamine-tained milk scandal sickened more than 52,000 children.

And in April, China stopped issuing unlimited multiple-entry Hong Kong visas to residents of neighboring Shenzhen, limiting their visits to once a week.

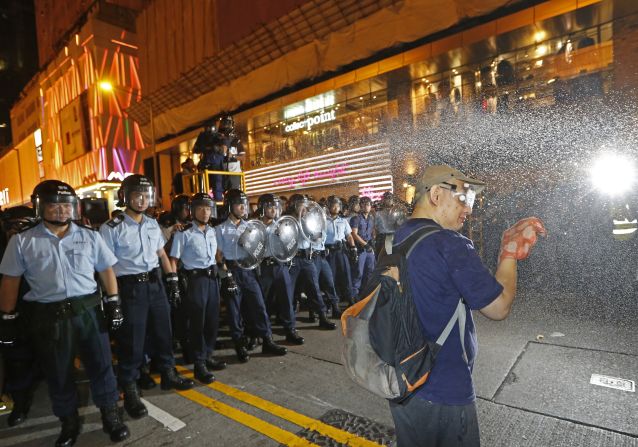

Still, several protests against mainland visitors took place earlier this year near Hong Kong’s border with mainland China, while this past week was marked by several ugly clashes. On Sunday, police were called in to break up a violent brawl between pro- and anti-China groups in the densely-populated Mong Kok shopping district, resulting in five arrests.

The following day, in what appeared to be an unrelated incident, Joshua Wong, an 18-year-old student leader and face of the pro-democracy protests, revealed he was assaulted after leaving a cinema.