Story highlights

West threatens consequences as Russia approves military action in Ukraine

Ukraine has been rattled by anti-government protests since November

The trigger then was the President's decision not to sign a trade pact with the EU

Ukraine is split: Some want to align more with the West, others favor Russia

Russia approved the use of military force in Ukraine on Saturday, despite warnings of consequences from the West, and Ukraine responded by saying any invasion into its territory would be illegitimate.

The acting prime minister has gone so far as to say that a Russian invasion would mean war and an end to his country’s relationship with Russia.

But there are so many questions as to how Ukraine arrived at this point: Why is Russia so interested in happenings there? Why does the West want to prevent Russian intervention? How did we get here? Why have thousands of protesters staked their lives, seemingly, on their desire for political change? And why has the government resisted their calls so vehemently?

Let’s take a look:

1. Why has Russia gotten so involved?

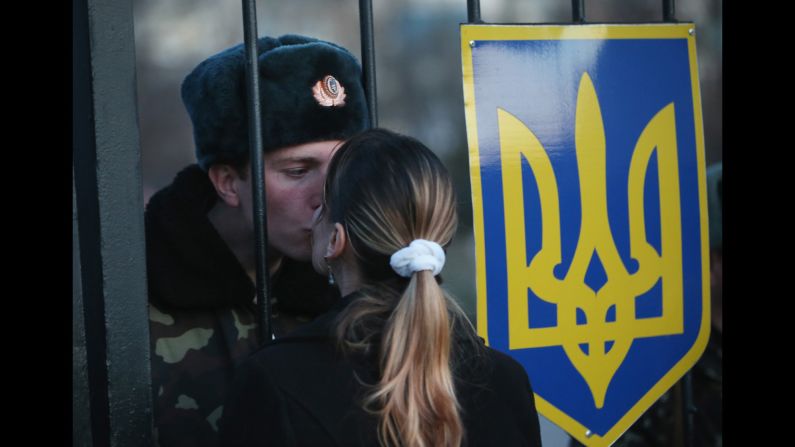

Eastern Ukraine and the Crimea have closer ties to Russia, while Western Ukraine is more friendly with Europe. Many Eastern Ukrainians still speak Russian, and the 2010 presidential elections divided the country with Eastern Ukraine voting heavily in favor of pro-Russia Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych. On Saturday, the Kremlin issued a statement that Russian President Vladimir Putin told U.S. President Barack Obama that Russia approved military action in Ukraine because it “reserves the right to defend its interests and the Russian-speaking people who live there.”

2. Hasn’t Yanukovych stepped down?

The Ukraine Parliament voted him out of power and he has fled to Russia. However, in a press conference Friday, the former President said – in Russian rather than Ukrainian – that he was not overthrown. He insisted he was still the boss and that he wants nothing more than to lead his country to peace, harmony and prosperity. While it’s unclear if he could return to power, Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations blamed members of the European Union for the bloody demonstrations that led to Yanukovych’s ouster.

3. What will happen in Ukraine if Russia sends troops there?

Top Ukrainian officials, including the acting President and prime minister, have said they are prepared to defend the country. They’ve also said that any invasion would be illegitimate, a response echoed by the United States, which has told Russia to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty.

4. Would there be international backlash to a Russian incursion?

The United Nations has warned Russia against military action, while Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon told Putin “dialogue must be the only tool in ending the crisis.” International leaders have also denounced the prospect of Russian involvement, while Obama has warned there would be consequences if Russia acted militarily.

5. What sort of consequences?

Obama hasn’t been specific other than to say Russia could face “greater political and economic isolation” and that the United States “will suspend upcoming participation in preparatory meetings for the G-8” in Sochi. Several Republican leaders in Congress have called on the President to take a tougher stand.

6. What are Obama’s options?

Sanctions, of course, top the list of options, but the United States will need to prepare for the backlash. Former presidential adviser David Gergen says Putin would consider any sanctions “small potatoes” compared to keeping control of Crimea, while Putin could pull his support for Obama’s initiative to reduce nuclear threats in the world, including in Iran. Christopher Hill, former U.S. ambassador to South Korea, Macedonia, Iraq and Poland, says imposing sanctions also raises the risk of alienating a superpower. “That means 20 years of trying to work with Russia down the drain,” he said.

7. What started the turmoil in Ukraine?

Protests initially erupted over a trade pact. For a year, Yanukovych insisted he was intent on signing a historical political and trade agreement with the European Union. But on November 21, he decided to suspend talks with the EU.

8. What would the pact have done?

The deal, the EU’s “Eastern Partnership,” would have created closer political ties and generated economic growth. It would have opened borders to trade and set the stage for modernization and inclusion, supporters of the pact said.

9. Why did Yanukovych backpedal?

He had his reasons. Chief among them was Russia’s opposition to it. Russia threatened its much smaller neighbor with trade sanctions and steep gas bills if Ukraine forged ahead. If Ukraine didn’t, and instead joined a Moscow-led Customs Union, it would get deep discounts on natural gas, Russia said.

10. Were there any other reasons?

Yes, a more personal one. Yanukovych also was facing a key EU demand that he was unwilling to meet: Free former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, his bitter political opponent. Two years ago, she was found guilty of abuse of office in a Russian gas deal and sentenced to seven years in prison, in a case widely seen as politically motivated. Her supporters say she needs to travel abroad for medical treatment.

11. What happened next?

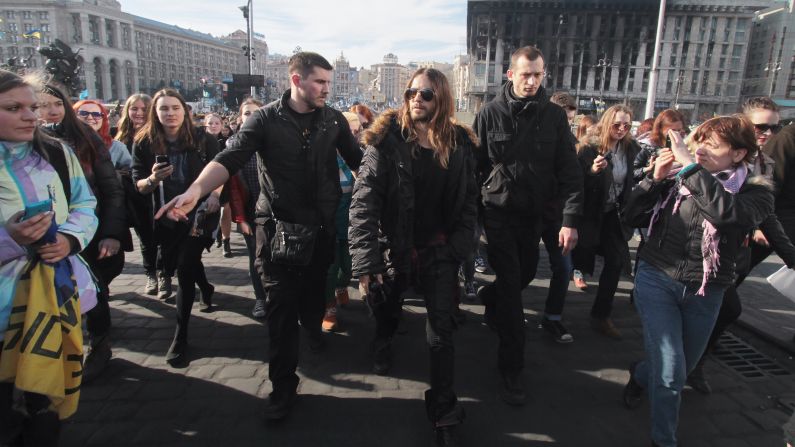

Many Ukrainians were outraged. They took to the streets, demanding that Yanukovych sign the EU deal. Their numbers swelled. The demonstrations drew parallels to Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, which booted Yanukovych, then a prime minister, from office.

12. Who’s heading the opposition?

It’s not just one figure, but a coalition. The best known figure is Vitali Klitschko. He’s a former world champion boxer (just like his brother Wladimir). Klitschko heads the Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reforms party. But the opposition bloc goes well beyond Klitschko and the UDAR. There’s also Arseniy Yatsenyuk.

13. How did Yanukovych react?

In a way that inflamed passions further. He flew to Moscow, where he and Russian President Vladimir Putin announced Russia would buy $15 billion in Ukrainian debt and slash the price Kiev pays for its gas. And then, when the demonstrations showed no signs of dying down, he adopted a sweeping anti-protest law.

14. What did the anti-protest law say?

The law barred people from wearing helmets and masks to rallies and from setting up tents or sound equipment without prior police permission. This sparked concerns it could be used to put down demonstrations and deny people the right to free speech – and clashes soon escalated. The demonstrators took over City Hall for the better part of three months.

15. But wasn’t the law repealed?

Yes, ultimately it was. Amid intense pressure, deputies loyal to Yanukovych backtracked and overturned it. But by then, the protests had become about something much bigger: constitutional reform.

16. What change in the constitution did they want to see?

The protesters want to see a change in the government’s overall power structure. They feel that too much power rests with Yanukovych and not enough with parliament.

17. What did the government do?

In late January, the President offered a package of concessions under which Yatsenyuk, the opposition leader, would have become the prime minister and, under the President’s offer, been able to dismiss the government. He also offered Klitschko the post of deputy prime minister on humanitarian issues. He also agreed to a working group looking at changes to the constitution. But the opposition refused.

18. Why did the opposition pass on the offer?

The concessions weren’t enough to satisfy them. They said Yanukovych had hardly loosened his grip on the government, nor had he seemingly reined in authorities’ approach to protesters. “We’re finishing what we started,” Yatsenyuk said.

19. Who was to blame for the clashes?

Depends on whom you ask. The government pointed the finger at protesters. The opposition, in turn, blamed the government.

20. What’s the takeaway here?

Street protests that started in November over a trade pact swelled into something much bigger – resulting in the former President fleeing to Russia for safety while still claiming to be the official leader of the country. With Russian troops rumored to be preparing for hostilities in the Crimea, the future of the region and the resulting effect on U.S.-Russian relations appears shaky.

READ: Truce crumbles amid gunfire in Ukraine

READ: U.S. talks tough, but options limited in Ukraine

READ: Opinion: ‘New’ Russia in Sochi: Same old Russia in Ukraine

CNN’s Marie-Louise Gumuchian and Antonia Mortensen contributed to this report