Story highlights

Psychologists have explored the link between creativity and madness for decades

Great artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch suffered from mental illness

Recent studies found that people in creative professions were more likely to be bipolar

Research also shows there could be an inherited trait that gives rise to creativity and mental illness

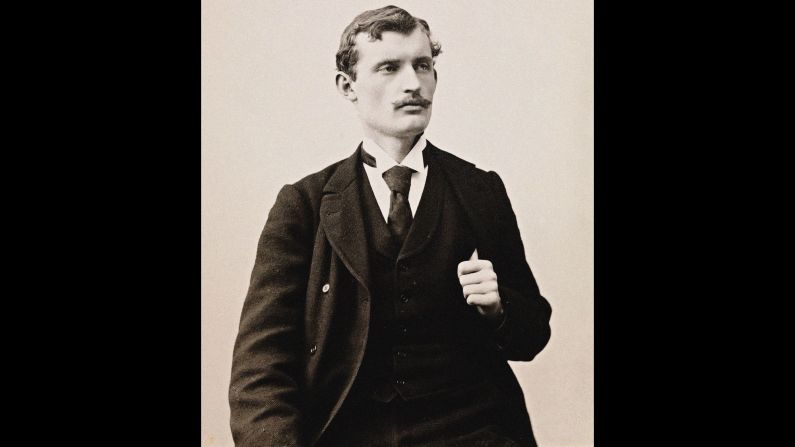

Celebrated Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s life was fraught with anxiety and hallucinations.

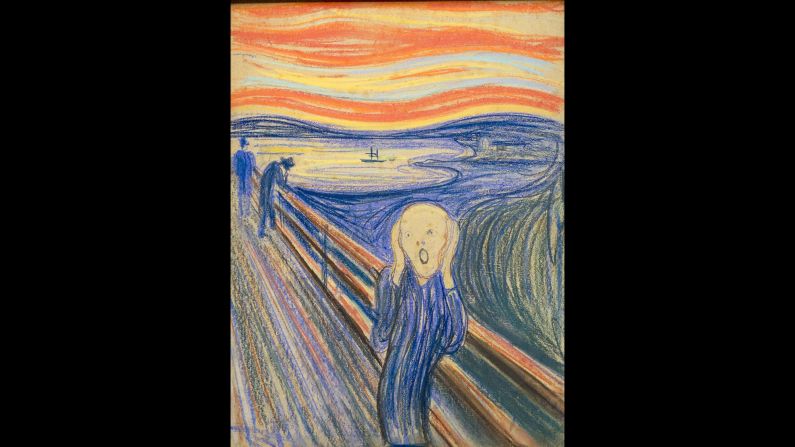

The painter, who died 70 years ago today, created one of the most recognized masterpieces in history, “The Scream”, which came to him in a sinister vision as he stood on the edges of Oslofjord.

“The sun began to set - suddenly the sky turned blood red,” he wrote. “I stood there trembling with anxiety - and I sensed an endless scream passing through nature.”

The painting is thought to represent the angst of modern man, which Munch experienced deeply throughout his life, but saw as an indispensable driver of his art. He wrote in his diary: “My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art.”

Munch may be one of the most high profile artists to walk the line between extreme talent and torment, but he is not the only one.

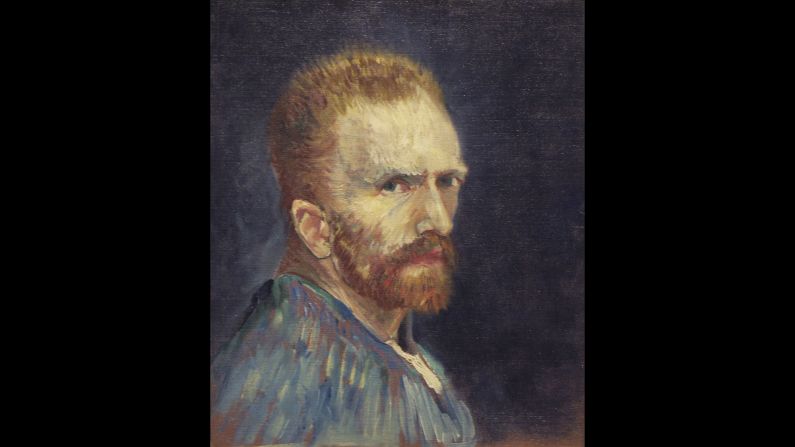

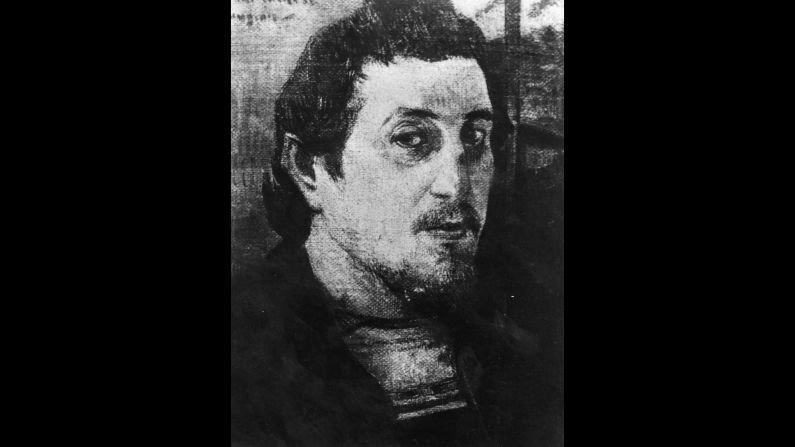

Vincent van Gogh, who cut of his ear after an argument with his friend Paul Gauguin, and later killed himself, swayed heavily between genius and madness.

In a letter to his brother Theo in 1888 he wrote: “I am unable to describe exactly what is the matter with me. Now and then there are horrible fits of anxiety, apparently without cause, or otherwise a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the head… at times I have attacks of melancholy and of atrocious remorse.”

These painters’ personal struggles still echo in popular culture today, and have given rise to the belief that artists are more susceptible to a range of mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

A growing body of research suggests that there is merit to that popular assumption. Madness may lurk where creativity lies.

The dark side of creativity

Psychologists have been fascinated by the potential link for decades. The earliest and most rudimentary studies examined eminent people across fields including literature and the arts.

These studies found that creatives had an unusually high number of mood disorders. Charles Dickens, Tennessee Williams, and Eugene O’Neill all appeared to suffer from clinical depression. So too did Ernest Hemingway, Leo Tolstoy and Virginia Woolf. Sylvia Plath famously took her own life by sticking her head in an oven while her two children slept.

Critics rightly pointed out that these studies focused on very specific groups of high-achievers, and that they relied on anecdotal evidence.

Subsequent studies have cast the net wider. Simon Kyaga led a team of researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute.

Read more: Life of a muse: What is it like to inspire art for a living?

Using a registry of psychiatric patients, they tracked nearly 1.2 million Swedes and their relatives. The patients demonstrated conditions ranging from schizophrenia and depression to ADHD and anxiety syndromes.

They found that people working in creative fields, including dancers, photographers and authors, were 8% more likely to live with bipolar disorder. Writers were a staggering 121% more likely to suffer from the condition, and nearly 50% more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

They also found that people in creative professions were more likely to have relatives with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anorexia and autism.

That is significant. Earlier studies on families have suggested that there could be an inherited trait that gives rise to both creativity and mental illness.

Some people may inherit a form of the trait that fosters creativity without the burden of mental illness, while others may inherit an amped-up version that stokes anxiety, depression and hallucinations.

There is anecdotal evidence supporting the connection. Albert Einstein’s son lived with schizophrenia, as did James Joyce’s daughter.

Keri Szaboles, a psychiatrist at Semmelweis University in Hungary, has studied the role genes may play more directly.

Szaboles gave 128 participants a creativity test followed by a blood test. He found that those who demonstrated the greatest creativity carried a gene associated with severe mental disorders.

Method in the madness?

Psychologists have established a link between mental illness and creativity, but they are still piecing together the mechanisms that underlie it.

In September neuroscientist Andreas Fink and his colleagues at the University of Graz in Austria published a study comparing the brains of creative people and people living with schizotypy.

Read more: Art and fashion, new BFFs?

Schizotypy is a less severe manifestation of schizophrenia. People with the condition may demonstrate odd beliefs (like a belief in aliens) or behavior (like wearing inappropriate clothes). Unlike schizophrenics, they do not have delusions and are not disconnected from reality.

Fink and his team recruited participants demonstrating low and high levels of schizotypy. They then slid them into a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine, and asked them to come up with novel ways of using every day objects. They later assessed the originality of their responses.

An interesting pattern emerged. Among those high in schizotypy and those who scored highest on originality, the right precuneus - a region of the brain involved in attention and focus - kept firing during idea generation. Normally this region deactivates during a complex task, which is thought to help a person focus.

Put more simply, the results suggest that creatives and those with high levels of schizotypy take in more information and are less able to ignore extraneous details. Their brain does not allow them to filter.

Scott Barry Kaufman, an American psychologist and writer for Scientific American, has summed up the results this way. “It seems that the key to creative cognition is opening up the flood gates and letting in as much information as possible,” he writes. “Because you never know: sometimes the most bizarre associations can turn into the most productively creative ideas.”

Clearly some people suffer for their art, and clearly some art stems from suffering. But it would be inaccurate to say that all creatives run the risk of mental illness.

Kyaga, the Swedish academic, points out that dancers, directors, and visual artists demonstrated mental illnesses less frequently than the general population.

Read more: Life imitating art: Astonishing ‘2D’ makeup transforms model’s face into famous paintings

Read more: Jameel Prize for art inspired by Islam awarded to female fashion duo