Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in July 2014 before the Costa Concordia was moved to Genoa to be dismantled, and before the ship’s captain was found guilty of manslaughter.

Story highlights

Foreign workers descended on Giglio, Italy after the Costa Concordia crashed there in 2012

Their arrival transformed the language, culinary scene and nightlife on the tiny Tuscan island

Islanders are trying to come to terms with what life will be like when the foreign crews leave

When the Costa Concordia and its salvage convoy finally depart Giglio, the residents of this picturesque Tuscan island will breathe a collective sigh of relief – and shed a collective tear.

Nothing much ever happened on Giglio before the doomed cruise liner crashed here on that fateful Friday the 13th in January 2012. There were the odd inconveniences, like when bad weather stopped the ferries and cut off the island from the mainland, leaving the local population of about 900 people with limited supplies.

The island had its fair share of tourists, but according to Mayor Sergio Ortelli, Germans came to camp and there were pockets of British who came to bird watch, but none of them left much of an impact. “We were a perfect place, a best kept secret,” he told CNN.

That all changed shortly after the Concordia ran aground, killing 32 passengers and crew as it capsized and then sank into the pristine coral reefs near the harbor on the eastern side of Giglio.

Within a few weeks of the disaster, foreign salvage crews moved in, first to defuel the crippled vessel and later to remove it. Italian with a Tuscan accent was no longer the language of commerce on the island. If the local businesses wanted to cater to the crews – some 600 workers from 29 different countries at the height of the operation– they had to learn at least a little bit of English, Dutch, German or Spanish. The languages have infiltrated the local dialect.

The locals have also had to adjust their menus and hours of business to accommodate the crews’ varied tastes and round-the-clock shifts. Suddenly, Giglio’s bars and pizza joints found themselves serving lunch fare at night for the workers who needed packed lunches for their graveyard shift – and beer at 7:00 am for the workers who were just coming in off the rigs who wanted an after-work drink.

“Our whole perspective changed,” Rosalba Brizzi, owner of Bar Fausto in the center of the port – a favorite spot for the salvage crews – told CNN. “No one ever challenged our way of doing things before. We were set in our ways and then suddenly our little island had to adjust to one of the most diverse populations anywhere in Italy. Can we go back to how we were before? I don’t know how to do that.”

Brizzi is one of the lucky Giglese whose business boomed when the crews came. She offered up a “lunch to go” service to make packed lunches for the crews to take on site, and allowed Titan Micoperi – the firm behind the salvage of the Concordia – to set up a credit system so workers could sign for their meals. And despite being forced to serve bacon and egg baguettes and chicken salad sandwiches with pickles, which she said she has yet to sample, she says she will miss the workers when they go.

“Our lives have been so enriched by this experience, and I don’t mean monetarily. I’ve met people from Samoa, from South Africa, from places I had never heard of,” she said, her eyes welling up with tears. “They’ve brought their families, they show us pictures from home. And now we will lose them all. They won’t come back.”

The sentiment is echoed along the port, where locals have given the ship nicknames like “the tomb,” “the dead whale” and the “astroship.” Trudy Brandaglia, an Australian who has had a tourist rental business on the island for nearly 30 years, said the salvage workers have become like family. “We will miss them terribly,” she told CNN. “We are going to be lost without them.”

The Giglese have adamantly refused to capitalize on the crash through tourist trinkets. You won’t find t-shirts that say “I got wrecked on Giglio,” or even models of the ship.

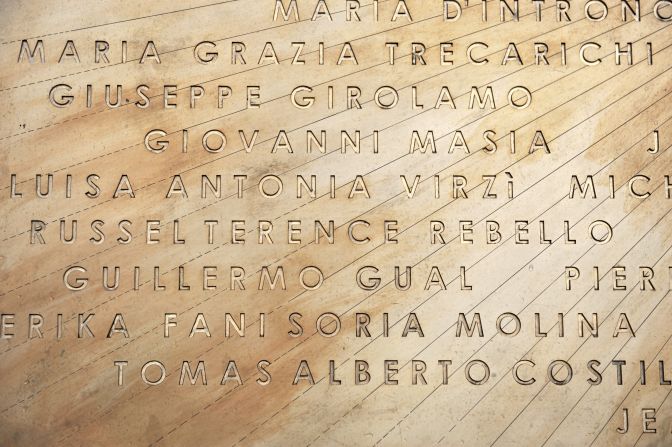

But the island does have two memorials to the 32 victims of the disaster and the Spanish diver who died during the salvage operation. One is a plaque with the victims’ names engraved on it affixed to the stone wall of the pier closest to the wreck. The other is a statue of the Virgin Mary donated by the husband of Maria Grazia Trecarichi, one of the last victims to be found. The statue’s neck is adorned with rosaries left by passengers and survivors’ families who have come to pay their respects on the island.

Father Lorenzo Pasquotti of the local Catholic church, which was a shelter for hundreds of passengers the night of the accident, has also created a museum in the church that includes life jackets from the ship, hard hats, a piece of rock from the bottom of the cruise liner and a tiny vial of oil from the Concordia’s engines, almost like a relic of blood from a saint. He also keeps a loaf of bread, meant to signify the feeding of the salvage crews, and the crucifix and communion tabernacle from inside the Concordia’s chapel.

Pasquotti also keeps the cards and letters passengers have written to Giglio to thank the islanders for their help. But Pasquotti’s church has scars, too. There is a crack in the apse from the underground drilling to remove the ship, which he says the workers have promised to patch up.

The crews working under the direction of Nick Sloane, the man overseeing the world’s biggest ever salvage project, have also been toying with the idea of leaving some sort of memorial made from the implements of salvage.

According to Sloane, workers have discussed building a funicular from the port to the town of Castello, high on a hill overlooking Giglio’s port. They may also try to leave behind some of the high-end fiber optic cables that were installed to give the island better Internet and phone service as crews hatched their plan to raise the Concordia. Giglio remains the epicenter of one of the most technically-advanced salvage operations on the planet, but you still can’t buy a cellphone or computer charger anywhere on the island.

Whatever emotional scars from the shipwreck remain on the island, the physical scars are worse. No matter how diligently crews work to clean up the implements of salvage, Giglio is indelibly marked with signs of the unspeakable tragedy that happened here.

Giglio’s pristine underwater ecosystem has been marred by the 30,000 bags of cement and grout poured into the reef, along with the pillars drilled deep into the island’s bedrock in order to support the giant steel platforms that cradled the Concordia for most of the past year. When all of the cement and steel is finally removed, the seabed will have to heal itself. All of the underwater grasses and mollusk fields that were relocated when the ship crashed will have to be moved back, even though they are thriving in their new environment.

Divers working on the site say the ship has also created a bizarre unnatural reef where fish and sea snakes swim among the pillars and in and out of the ship’s broken windows. Several local dive companies want to create a new reef and dive school using the steel platforms that propped up the Concordia. But Gian Luca Galletti, Italy’s environmental minister, says that is not an option, even though the Giglese have been presenting redevelopment plans that include keeping the platforms in place.

“The platforms will be dismantled,” Galletti told CNN, before adding that this was an Italian decision – not one that could be made solely by the people of Giglio. “We have always hypothesized from the beginning that Giglio would be returned to the same state as it was before the shipwreck and there were no platforms before the shipwreck.”

Franca Melis, who owns a popular restaurant in Castello and a dive company in Giglio’s port, disagrees. “It is a mistake to remove them when we could have one of the best dive sites in the world if we leave them,” she told CNN. “It will disrupt the seabed for another two years to pull them out, like a rotten tooth from the seabed. Let’s try to see the bright side and use them to bolster the local economy.”

“When the ship is gone, it will be like this island is dying twice. Let’s try to save ourselves. We are going to die here without that boat.”