Editor’s Note: Dr. Andrew E. Simor is chief of the Department of Microbiology and the Division of Infectious Diseases at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. He is senior scientist at Sunnybrook Research Institute and a professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto. The opinions in this commentary are solely his.

Story highlights

SARS killed 38 people in Toronto; Dr. Andrew Simor says there were lessons learned

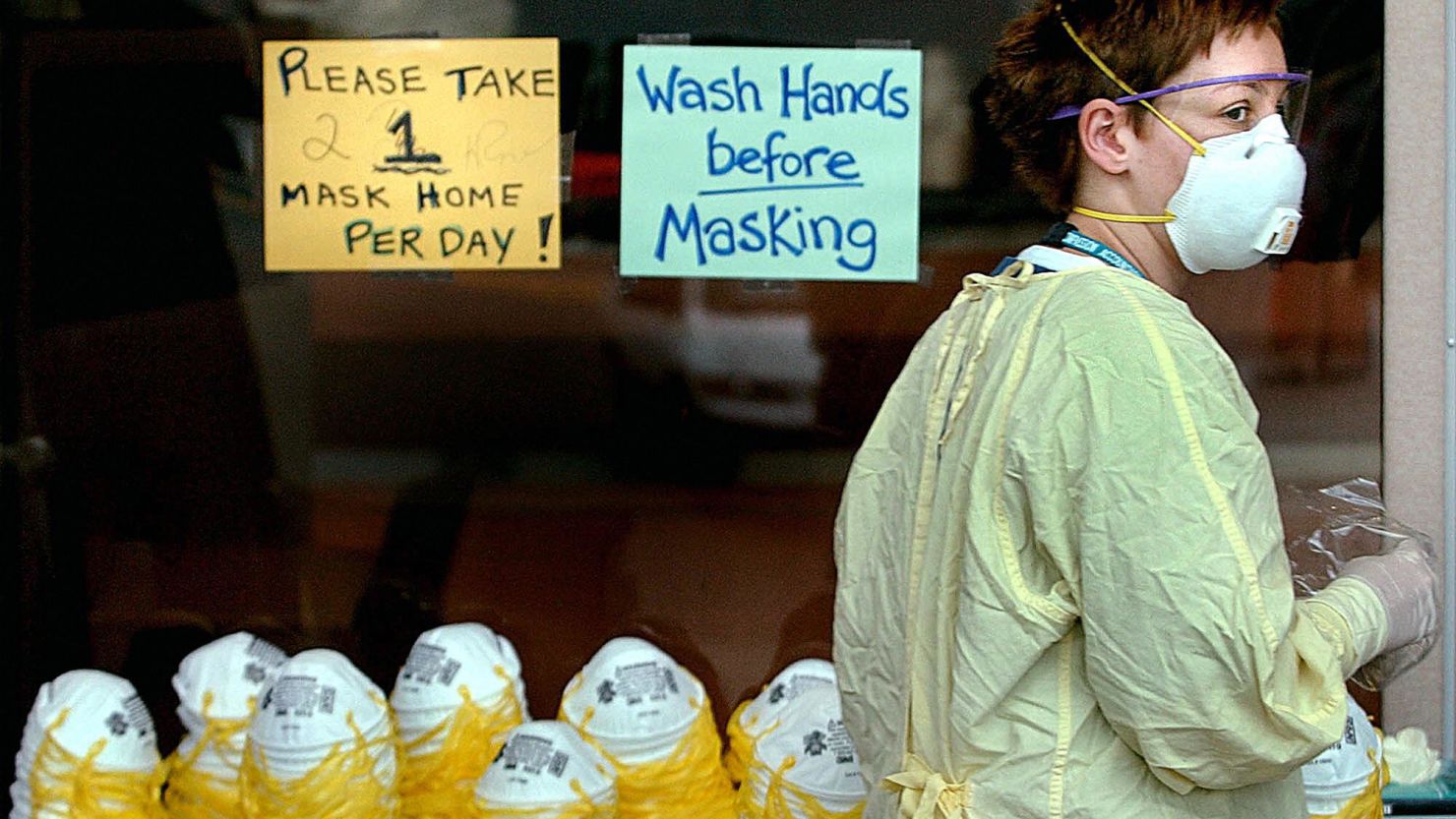

He says staff learned to screen patients and to suit up with protective equipment

The rules of good hand hygiene also become vital in dealing with disease, he says

Managing Ebola demands as much of our diligence in infection control practice as SARS did. And though Ebola may, in theory, be less contagious than the airborne SARS or Middle East respiratory syndrome viruses, it is spread through direct contact with infected body fluids or organs and has been demonstrably and tragically more fatal.

The SARS experience in Canada, though harrowing at the time, has helped us better prepare. In 2003, 224 people in Toronto were diagnosed with SARS, and 38 people died. SARS, which stands for severe acute respiratory syndrome, had originated in China and became a worldwide epidemic.

No longer are highly infectious diseases a world away. We have become more sensitive about just how global any infectious disease can be, and that it’s easy enough to “import” a disease.

SARS also reminded us that many infections may be spread and acquired by patients, visitors and staff in health care settings.

After SARS, that sensitivity translated into planning and implementation for the eventuality that a patient with another infectious disease may present at our door.

We are ready with protocols in place, in particular for adequate screening with the travel history of new patients, providing health care providers with personal protective equipment and ongoing training in its appropriate use, and ensuring rigorous environmental cleaning practices for all patient care areas.

We regularly engage our health care providers on the critical importance of knowing how to appropriately put on and remove personal protective equipment.

We have the advantage of learning from experiences in West Africa. Many of the centers that have been set up for dealing with Ebola patients there now use a buddy system to help ensure that everyone puts on and takes off personal protective equipment in the safest way possible, and we are going to be implementing that policy here.

The SARS experience also increased our emphasis on proper hand hygiene. One cannot just rely on the barriers like personal protective equipment. We need to also rely on the important and fundamental practice of cleaning one’s hands. Proper hand hygiene includes washing with soap and water, or use of an alcohol-based hand wash rub, before and after each patient contact.

We and other facilities across the country conduct regular audits for hand hygiene compliance.

Planning and implementation require resources and expertise, and there is no question that after SARS, nationally and federally, our government acknowledged and addressed the need to strengthen our public health services.

Hospitals were given additional resources to ensure they had appropriate infection prevention and control infrastructure, including adequate isolation facilities across the country.

Hospital accreditation standards and guidelines were also substantially bolstered to ensure adequate attention to infection prevention and control. More policies were developed to address these kinds of wide-impact infectious diseases scenarios.

SARS also taught us the importance of communication, consistent messages, and accountability for dealing with these types of wide-impact events, and of making everyone aware – both internally to patients and staff, and externally to the community served by the hospital – of the situation and what measures were being implemented. Today, our lines of communication are much more open.

We began a planning process months ago in collaboration with public health agencies for the eventuality that an Ebola patient may present at our hospital. It is not an eventuality we look forward to, but given the lessons we have learned, we are better informed and prepared.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.