Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for The Miami Herald and World Politics Review. A former CNN producer and correspondent, she is the author of “The End of Revolution: A Changing World in the Age of Live Television.” Follow her on Twitter @FridaGhitis. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Frida Ghitis: These are tough times for idealistic pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong

Ghitis: Let's hope there won't be a repeat of Tiananmen Square violence

She says China appears unwilling to allow flexibility, so protesters have few options

Ghitis: Even if the standoff leads to Chinese crackdown, other nations will unlikely to interfere

These are tough times for idealistic revolutionaries. Pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong know that taking on the Chinese government has never been an easy task. Their chance of success gets worse by the day. There are signs that this could end badly.

China’s Communist Party is sending clear messages that it has no intention of yielding to the protesters’ demands, warning of “unimaginable consequences” if the protests don’t end soon.

The worst case scenario is that these peaceful and highly disciplined protesters could end up crushed by the Chinese regime just as their predecessors were in 1989 at Tiananmen. Yes, the arc of history tends to bend toward justice, but the conditions and timing have to be right.

Based on official statements, China is in no mood to be pressured to change. The international community is too worried about the instability in the Middle East and too busy to meddle with China’s political problems.

Hong Kong’s activists, who were prepared well for this moment and are committed to avoiding violence, have the moral support of people beyond China’s borders, but not much more. And China believes it has little to fear from international reaction.

When the United States issued mild statements in support of an “open system” and the “highest possible degree of autonomy” for Hong Kong, Beijing promptly shot back that this is China’s internal domestic affair and others should stay out.

Sure, if China brings about a bloodbath in Hong Kong, investors may take their chips and go to Singapore or other competing regional hubs. It is not completely risk-free for Beijing to go on the offensive against peaceful protesters. But China is controlling the message at home, trying to inoculate the country from a pro-democracy contagion. It would rather avoid a nasty confrontation, but it may decide at some point that a prolonged standoff is riskier than a swift violent crackdown.

China’s highly self-assured president, Xi Jinping, has three possible courses of action, and all the evidence is that he has ruled out the one leading to compromise.

Instead, he has issued his response in language that signals complete inflexibility. The Communist Party newspaper presented Xi’s position almost as a doctrine, practically written for long-term use.

They called it “The Three Unwaverings,” a determination to continue on the current course of implementing the existing policies of “one country, two systems,” in “advancing democratic development according to the law,” and in “safeguarding long-term prosperity and stability.”

When China speaks of safeguarding stability, it means change will come – if at all – very slowly and under the complete control of the central government.

The Hong Kong students, in contrast to the Tiananmen Square protesters, are not demanding that China become a democratic country. Their demands are much more modest. All they want is Beijing to keep its word.

When Hong Kong stopped being a British colony to join China in 1997, Beijing agreed voters there would choose their own leaders through universal suffrage by 2017. Now China has said all voters in Hong Kong can participate in those elections, but they will have to choose between candidates approved by a committee loyal to Beijing’s leaders.

That’s not true democracy, the protesters say, quite correctly.

The man who helped negotiate the 1997 handover, the last British governor of Hong Kong, agrees that Beijing is in brazen violation of the agreement.

But President Xi, who has been adding to his authority and may have already become the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao, is not going to let the masses of democracy-loving people in Hong Kong tell him what to do. More importantly, he will not allow them to give the rest of China any crazy ideas about choosing their own leaders or about pressuring the authorities to make concessions by holding protests.

China’s Communist Party worries about three things over all others: social stability, economic growth and its hold on power. They view anything that threatens one of those goals as a challenge to be quashed. A mass protest demanding democracy in the most prosperous city in the country – Hong Kong’s umbrella revolution – threatens all three, even if the protesters are not trying to overthrow the Communist Party’s rule.

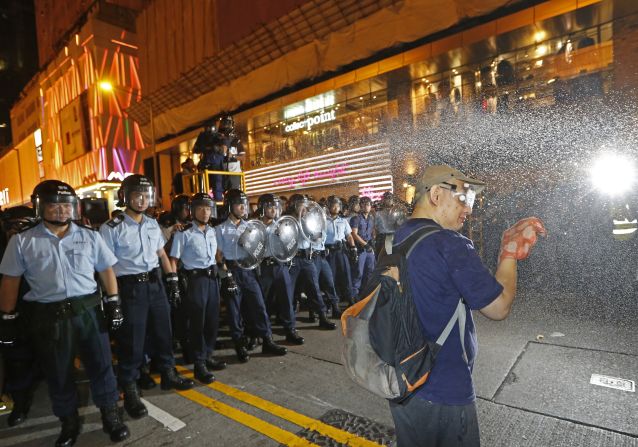

Xi has already been trying to maneuver through an economic slowdown. Periods of economic uncertainty are the most dangerous times for a political system. Activists in the mainland say he has already tightened repression and surveillance against dissidents. And that was even before the umbrellas came out in Hong Kong and volleys of tear gas persuaded tens of thousands of people to come out in support of the young protesters.

For now, Beijing is allowing the local government in Hong Kong to deal with the crisis. But its patience is wearing thin. The students are digging in, persuaded of the rightness of their cause.

If Beijing does send out the troops – the People’s Liberation Army forces already garrisoned close to where the “umbrella revolution” demonstrators are holding their protests – international reaction will prove even less determined and more ineffective than it did in Beijing after that tragic night in Tiananmen Square 25 years ago

Beijing knows that if it crushes the protests, there will be little appetite in other countries for major economic sanctions against China. Both rich and poor economies have become reliant on Chinese markets.

If it’s any consolation, this moment is not lost. The times are tough for democratic revolution, but history really is on the side of protesters. As Hegel said, history steadily brings the awareness of one’s freedom, followed by its realization. Hong Kong is gaining that awareness. But achieving true democracy will take longer.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine