Every week, Inside Africa takes its viewers on a journey across Africa, exploring the true diversity and depth of different cultures, countries and regions.

Story highlights

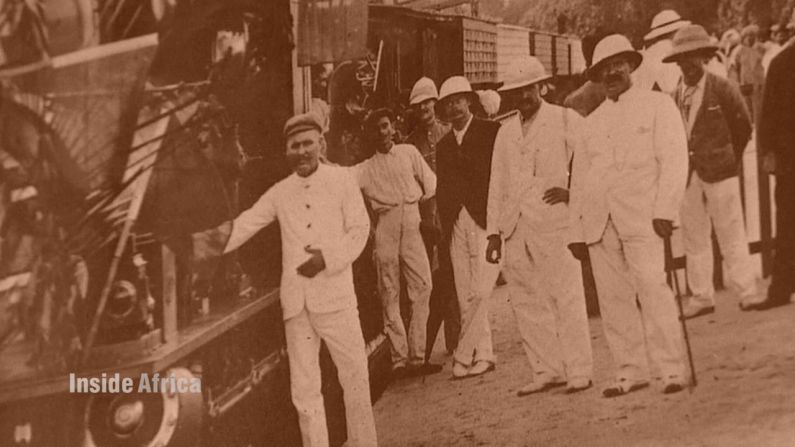

Indian migrants flocked to Kenya just over a century ago to build railways

Lion attacks and diseases such as black fever were just a couple of the dangers workers on the railways faced

Many descendants of those Indian migrants are today successful business owners across Kenya

Some say that the Indian community has still not fully integrated into Kenyan society

At the Old Port in Mombasa, southern Kenya, tranquil waters lap gently against the shore beneath the ghostly Fort Jesus garrison.

Today, it’s a pretty and peaceful scene, but one that belies the port’s bustling colonial past.

It was at this spot just over a century ago that the ancestors of Kenya’s successful Indian community first set foot on African soil.

They came in ships and dhows, having been coaxed here to build one of the continent’s great railways.

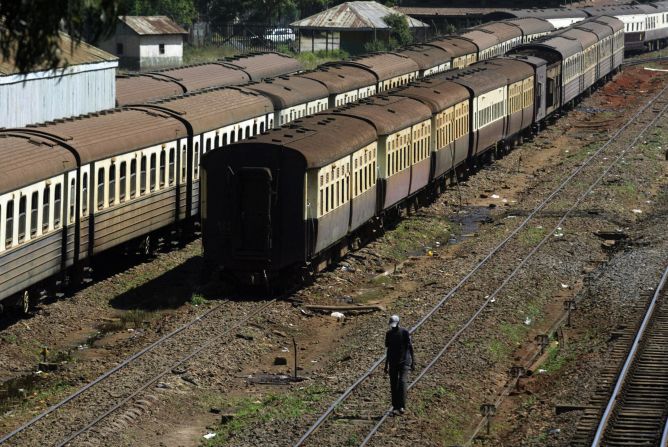

As that railway – which was soon christened the “lunatic line” because of its high cost and the dangers faced by those constructing it – snaked through the country towards Uganda in the years that followed, so did the Indian community.

The economic and cultural roots they laid down beside the tracks remains to this day.

“(My family is involved) in quite a lot,” said one businesswoman of Indian heritage we meet in a nearby restaurant. “We have commodities, transport and various other things.”

She tells us her grandfather first came to Kenya to work on the railways and her family has been there ever since.

Her colleague chimes in that “Indians have been traders and economically they play a very big role in the Kenyan economy.”

At a spice shop just down the road, meanwhile, the third generation Indian owner tells me that Kenyan Asians are spread widely across industries like construction, retail and tourism.

The winds of trade

Of course, merchants from India and what’s now known as Pakistan had come to Mombasa long before the railway.

The trade-routes linking East Africa and Asia were already well established.

Mombasa had been a city-state for over 2,000 years bearing long and fruitful relations with the Middle East, Asia and the Far East.

In the port’s heyday “there was ivory being sold like the way we sell cakes now or mahamris as we call them,” said historian Satmbuli Abdillahi Nassir. “There was rhinoceros horns … there was dry skin, there was spices, all this was happening at this port.”

It was the railway lines, however, and the need for labor that first brought a mass migration of people from the sub-continent.

By the mid-1890’s, the British were effectively in control of Kenya and were keen to open up the country’s interior and that of neighboring Uganda to counter German influence in the region.

Having started construction of railway lines in India nearly 50 years earlier, Punjabi engineers and laborers had the skills the British required.

The lion’s share

More 30,000 indentured Indian workers were soon enticed to sail to Mombasa and a new life in Africa.

The country these expectant migrants found upon arrival, however, was vastly different to the land of comparative business opportunity their ancestors inhabit today.

Work on the railways was brutally hard. By the time it had reached its destination in Kisumu on the banks of Lake Victoria, roughly 625 miles from Mombasa, around 2,500 men had died. That’s four people for every mile.

And it wasn’t just the oppressive heat and long hours workers had to contend with.

The man eaters of Tsavo were a pair of lions that killed anywhere between 28 and more than 100 workers during the building of the railway, depending which account you believe. They spread such terror that work stopped until they were eventually shot.

On top of that, there was also sickness and disease to contend with.

“Many people died of malaria and black fever when they were building because of the difficult terrain and there were no medical facilities resulting (in) many deaths,” said Komal Shah, whose ancestors settled just outside Nairobi after the railway was built.

“They had to take risks coming to this place,” she added.

Melting pot

Shah is one of the many Kenyan Asians who today run their own businesses in the Westlands and Parklands districts of the Kenyan capital.

She teaches the ancient Indian discipline of yoga, a far cry from the grueling and punishing work of the railway lines.

But the history and contribution of Shah’s ancestors in building the community and the infrastructure of the country make her proud of her roots.

“I would not like to be distinguished as a Kenyan from a different region of the world,” Shah said. “I am born here and a third generation Asian Kenyan. I proudly say that I am a Kenyan.”

Such open and patriotic sentiments aren’t uniform across the country, however. Outside of the big metropolises such as Nairobi and Mombasa, there is a more complex relationship between communities.

In Kisumu, where the great railway ends, issues of integration between Kenyan Asians and black Africans remain.

Although there are rarely tensions between the groups, neither mixes fully with the other. According to local MP Shakeel Shabbir Ahmed, himself a Kenyan Asian who married a black Kenyan woman, this is something that has to change.

“There has not been a real integration (in Kisumu) … like in Mombasa and Dar es Salaam,” Ahmed said.

“In Kisumu the integration is only when it’s in the shop or at the business … but when they go out of that particular environment there is very little integration either by way of recreation or other facilities.”

While Kenyan Asian’s community makes a substantial economic contribution to wider society, Ahmed believes they should make more of an effort to mix with their compatriots and refrain from being “insular.”

“We are less than 1.4% (of the population) here in Kenya but we hold the purse strings to maybe 30% or 40% of the economy,” Ahmed estimates.

“(But) we must remember that if we earn here, we live here, we must contribute to this country.”

That’s a sentiment that the very first Indian emigres to set foot in this beautiful country would have doubtless agreed with.

Read: The world’s most famous chimps