Story highlights

Bishops bickered throughout a major meeting on Catholic doctrine

Pope Francis kept largely silent throughout the debate

Catholic teaching is not easy to change

As Catholic bishops in Rome began a major meeting on modern family life two weeks ago, Pope Francis encouraged them to speak candidly and “without timidness.”

He certainly got what he asked for.

Bishops bickered. Conservatives contemplated conspiracy theories. Liberals lamented their colleagues’ rigidity.

Through it all, the Pope stayed silent.

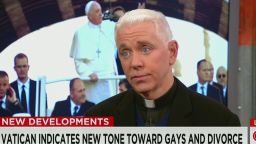

Even when a report emerged from the bishops’ meeting that welcomed gays and lesbians in strikingly open terms, Francis didn’t say a word.

Even when that welcome was watered down, not once, but twice, and then, on Saturday, largely scrapped, the Pope revealed nothing.

By the midpoint of the meeting – officially called the Synod of the Bishops on Pastoral Challenges to the Family – conservatives were complaining that Francis had “done a lot of harm” by not making his own views known.

But if Francis had spoken, it would have shut down the very debate he wanted to spark, Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, a close ally of the Pope’s, told reporters.

“Roma locuta, causa finita,” Ravasi said. That’s Latin for, “Rome has spoken, the case is closed.” (The Pope is the bishop of Rome.)

Finally, as the meeting closed on Saturday afternoon, the Pope addressed the nearly 200 bishops he had summoned to Rome.

In a widely praised speech, he told them the church must find a middle path between showing mercy toward people on the margins and holding tight to church teachings.

What’s more, he said, church leaders still have a year to find “concrete solutions” to the problems plaguing modern families – from war and poverty to hostility toward nontraditional unions. A follow-up meeting is scheduled for next October in Rome.

All of this may raise a few questions in people’s minds. If the Pope is the head of the church, why can’t he just make changes on his own? Why are so many Catholics resistant to revising church teaching? And what does all of this have to do with Jesus?

Here are some things to keep in mind.

WWJD?

Jesus didn’t often talk about practical matters, scholars say, but he did talk about divorce.

“I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another woman commits adultery,” Jesus says in the Gospel of Matthew.

That statement may sound reactionary today, said Candida Moss, a scholar of New Testament and early Christianity, but it was actually pretty progressive at the time.

“In a world in which women had to be married to be successful,” she said, “being this stringent about divorce actually helped those women.” It especially helped women callously discarded by their husbands, which was allowed under Mosaic law, Moss added.

So, when Catholic bishops debate whether to allow divorced and remarried Catholics to receive Communion – as they did in Rome over the past two weeks – many bring up this teaching from Jesus.

If Jesus said it, the logic goes, the church can’t change it.

Tradition

The Catholic Church traces its roots to Peter, whom Jesus gave the keys to heaven and who is considered by many to be the first bishop of Rome – a sort of proto-pope, if you will.

Between then and now, a span of more than 2,000 years, the church has accrued layers upon layers of teachings and traditions. Catholics call this the “deposit of the faith,” and many conservatives say the job of modern church leaders is to guard it, not change it.

In fact, as truth – with a capital T – some conservatives argue that even the Pope can never change it.

“The Pope, more than anyone else as the pastor of the universal church, is bound to serve the truth,” Cardinal Raymond Burke, a leading conservative, told Buzzfeed recently.

“The Pope is not free to change the church’s teachings with regard to the immorality of homosexual acts or the insolubility of marriage or any other doctrine of the faith.”

Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York, another prominent church leader, suggested that doctrine could change, but only if the Pope called an ecumenical council.

More liberal church leaders argue that core Catholic teachings can evolve over time, as they did, for example, on slavery.

“Doctrine develops,” German Cardinal Reinhard Marx said last week. “Saying that doctrine will never change is a restrictive view of things.”

In the war of words between conservative and liberal Catholics, the biggest battle is here: what can and cannot change about the church’s moral tenets.

The church universal

The Catholic Church has an estimated 1.2 billion members spread across hundreds of countries from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. In many of those countries, ethics, particularly sexual ethics, differ widely.

For instance, in Africa, 75% of Catholics believe that divorced and remarried Catholics are “living in sin” and should not receive Holy Communion. In the United States and Latin America, just 30% agree.

On same-sex marriage, the gulf is just as wide. Africa (99%) and the Philippines (84%) reject same-sex marriage, while a slim majority of Catholics in the United States support it.

The Pope, as head of the whole Catholic Church, has to consider all of his far-flung flock – not just cater to a particular segment, said the Rev. James Martin, a Jesuit priest and author of the book “Jesus: A Pilgrimage.”

“While he is interested in being prophetic and moving things forward, you can’t move so fast that you lose an entire wing or geographic section of the church.”

The old guard

For nearly 35 years, the Catholic Church was led by two popes – Saint John Paul II and Benedict XVI – who held fast to traditional church teachings, and part of their mission was to appoint hundreds of bishops who share that view.

As a result, conservative bishops hold top positions in many dioceses across the world and in the Vatican itself.

“These are people who have spent a lot of time accruing power and supporters, and they feel very strongly” about the church not changing, Moss said.

Since his election in 2013, though, Francis has slowly but surely reversed that trend.

The Pope has appointed moderates in several big dioceses, including in Chicago earlier this fall, and he’s removed some archconservatives from their posts.

Burke, for example, who is something of a hero to traditionalists, confirmed last week that he’s been ousted from the Vatican’s supreme court.

So, while many liberals expressed disappointment that the bishops’ surprising welcome to gays was later retracted, others argue that at least the topic is still on the table for the next year’s meeting, when the church will make final decisions on these issues.

Put another way, taking “three steps forward, two back, is still going forward,” said Marx.