Call it “Breaking Bad” on the border, only bigger. Apparently much bigger.

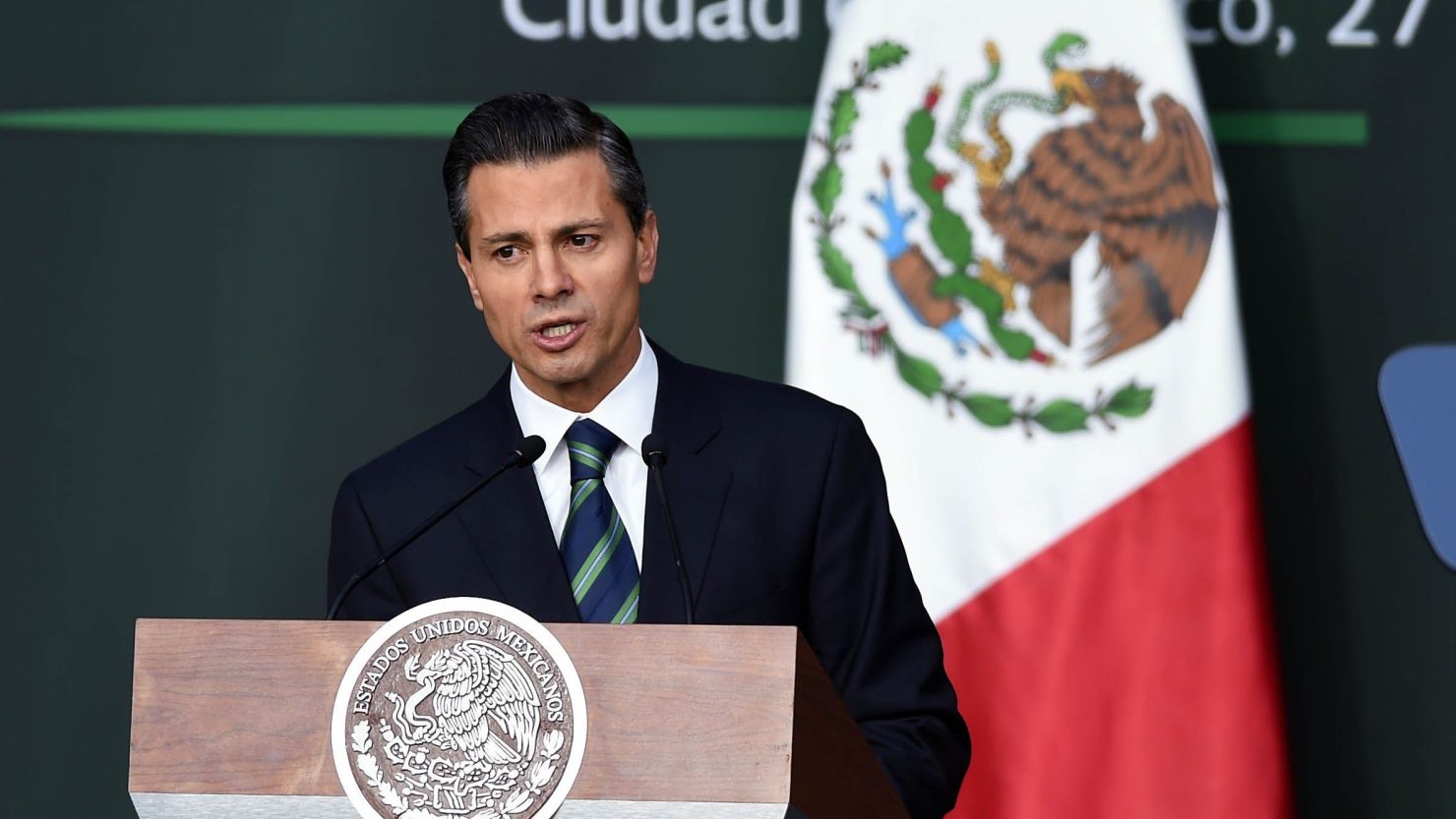

Even before Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto arrived at the White House on Tuesday for a snowy morning meeting with President Barack Obama, senior administration officials had already highlighted new “border enforcement priorities” to enhance “national security and safety” at the southern border.

The meeting comes at a time when U.S. Border Patrol agents in San Diego have just reported an enormous increase in confiscation of methamphetamine in California’s southernmost large city. San Diego’s border patrol said that methamphetamine seizures increased in the 2014 fiscal year by a whopping 43%. And meth seizures in just that one area accounted for almost half (47.7%) of all the methamphetamine seized by the Border Patrol nationwide.

READ: U.S. immigration says more Central Americans apprehended than Mexicans

The spike in meth confiscations is both cause for alarm in Washington, and also a signal that efforts to control access to chemicals used to make meth in the U.S. may be paying off.

Dave Gaddis, former chief of global enforcement for the Drug Enforcement Administration, said the flow of the drug across the border is adding to a “dwindling supply” of meth that is already in the United States.

“Because of more effective law enforcement, you don’t have the large labs that will manufacture the amounts that the demand [in the United States] is requiring,” he said.

The other good news is that there is no concrete evidence that the amount of methamphetimine use in the U.S. has spiked. The 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health suggests the number of meth users has neither risen nor fallen significantly since 2011.

But here is the problem for U.S. law enforcement: Cooking and smuggling meth has become much more of an international business. Small homegrown labs in someone’s house used to create a lot more of the product, with all the associated risk including fires and explosions and, of course, arrests.

Now, Mexican drug cartels are suspected of manufacturing as much as 90% of the available quantities of the drug and shipping it across the border, along with other drugs including cocaine and marijuana. In earlier days when the homegrown version of the drug was more popular, Gaddis said law enforcement might have encounted “10 to 12, maybe 16 ounces” of the drug at a time.

“But down there? They’re manufacturing 500 kilos at a time,” he said.

The illegal drug markets could flood, thanks to the large volume of meth the cartels can supply, Gaddis said.

“Prices could go down. And if prices do go down, because of the nature and violence of that particular drug, we’re going to see emergency room visitations increase,” he said. “We’re going to see [overdoses] increase. More homicides.”

So why would Mexican drug cartels want to get involved in the meth business anyway? Many experts see the law of supply and demand at work.

Brian O’Dea, a former drug smuggler and author of the book, “High: Confessions of an International Drug Smuggler,” said the precursor chemicals to make meth are readily available in Mexico. And it’s very easy to do.

“You can build the product in Mexico with impunity pretty much,” he said. “You can pay for protection. To cross the U.S. border from Mexico, there are a whole lot of people willing to take that chance and to get the drug across the way that illegal aliens come across that border.”

What to do about it?

Gaddis said in years past, law enforcement shifted its priorities and took the focus off of meth, which may have given it an opening to grow.

“You can’t keep your eye on 10 balls at one time,” he said. “It’s a very nasty drug. It does a lot of damage physiologically to people. I hope we take another look at it and try to build another program that blocks a lot of that.”