Editor’s Note: Brigid Schulte is author of “Overwhelmed: Work, Love and Play when No One has the Time,” a fellow at New America and a staff writer at the Washington Post. This is the second in a series, “Big Ideas for a New America,” in which the Washington-based think tank New America spotlights experts’ solutions to the nation’s greatest challenges. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

In the United States, white-collar workers work longer than peers in most advanced countries

Brigid Schulte: We need to recapture our lost leisure; more work doesn't raise productivity

She says companies reward workers for how long they sit at their desks, not for what they do

What if I hadn’t worked so hard? What if … I had actually used … my position to be a role model for balance? Had I done so intentionally, who’s to say that, besides having more time with my family, I wouldn’t also have been even more focused at work? More creative? More productive? It took inoperable late stage brain cancer to get me to examine things from this angle. –Eugene O’Kelly, former CEO, KPMG

While working on “The Last Supper,” Leonardo da Vinci regularly took off from painting for several hours at a time and seemed to be daydreaming aimlessly. Urged by his patron, the prior of Santa Maria delle Grazie, to work more continuously, da Vinci is reported to have replied, immodestly but accurately, “The greatest geniuses sometimes accomplish more when they work less.” –Tony Schwartz, “Be Excellent at Anything”

In his 1932 classic essay, “In Praise of Idleness,” Bertrand Russell heralded a coming time when modern technology would bring shorter work hours and time for leisure to be enjoyed equally by everyone.

Work and leisure both would be “delightful,” and the world would be the better for it. “Every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving … Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness and dyspepsia.”

Russell, along with scholars like Josef Pieper, author of “Leisure, the Basis of Culture,” thought that it is in moments of leisure that civilization gets created. Both were extraordinarily productive, despite their call for what may today be seen as slacking.

But they argued that it is only when we take the time to lift our noses from the grindstone and are not busy with the getting, making and doing that ensures our survival, that flights of imagination, bursts of insight can lead to inventions like the wheel, art, philosophy, literature, scientific discoveries and innovation.

At the turn of the 20th century, leisure time was the ultimate status symbol, a way not only of conspicuously showing off your wealth, but of your ability to enjoy the best that life had to offer. Even those without wealth in the labor movement sought a living wage and shorter work hours so they could, as a famous protest song of the time put it, not only have their bread, but the time to enjoy the roses, the fruits of their labor.

Ironically, it was only when Henry Ford took the wildly controversial step of shuttering his automobile manufacturing factories on Saturday and cutting daily work hours from the then-standard 12 to 8 that workers began not only enjoying leisure time at home, but became more efficient and productive at work.

Though his fellow captains of industry screamed in protest, Ford had based the decision on his own in-house research of how far he could push manual laborers before they became so exhausted or resentful that they’d begin making costly mistakes. Within a few years, the Ford way became the industry standard, and thus was born the 40-hour work week.

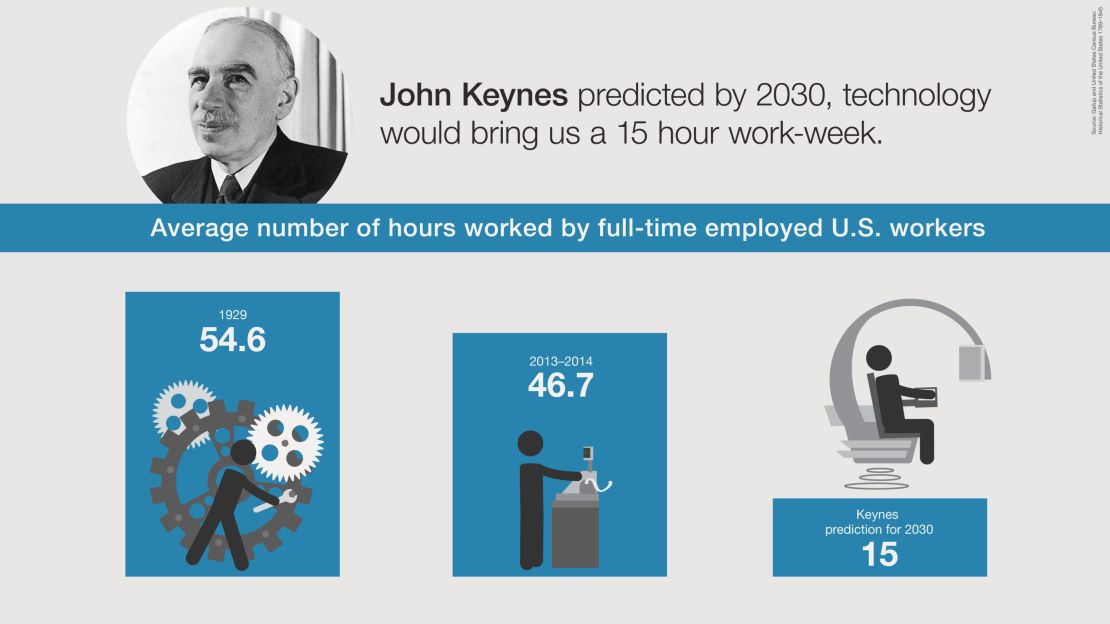

Economists, too, began making rosy predictions of a coming age of abundant leisure. Keynes thought that by 2030, we’d be working a 15-hour work week, and all would have time to enjoy “the hour and the day virtuously and well.” Others predicted a 22-hour work week, six-month work year or a standard retirement age of 38. If anything, thinkers at the time worried about what the masses would do to occupy themselves with so much free time on their hands. The predictions seem ludicrous now.

In the United States, white-collar workers work longer and more extreme hours than their peers in just about any other advanced economy, save South Korea, where the Wall Street Journal has reported overworked Koreans are checking themselves into prison-like meditation retreats just to get away from it all, and Japan, where they’ve even coined a word for death from overwork: karoshi. (No one leaves until the boss leaves. And the boss never leaves.)

Workers in the United States give up among the most vacation days. We are the only advanced economy with no national vacation policy ( see how we stack up in the chart below). And technology has enabled not just flexible work, but for work to seep into every corner, every hour and every minute of the day.

The 40-hour work week of Ford’s legacy can seem like a cruel dream – the labor policy that later enshrined it, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, now perversely gives businesses incentive to work salaried workers to the point of burnout, and to keep hourly workers’ hours artificially low to avoid paying benefits or overtime.

Salaried workers have too little leisure time that they can choose and control, what leisure scholars say is the essence of pure leisure. And hourly workers, too much. Though without either choice or control, those blank, unfilled hours of insecurity and gnawing anxiety can hardly be called leisure.

Just as with income inequality, our experience of work and leisure is increasingly diverging. As millions of Americans remained sidelined from the economy, working far less than they’d like, and for a minimum wage that in no major city in the country could cover the cost of a two-bedroom apartment, others wear long work hours like a badge of honor.

Economists have found that our workplaces reward employees by how long they sit at their desks in the office, not for what they do. Leisure is seen as unproductive at best, and frivolous or a waste of time at worst.

And that’s not just stupid, it’s dangerous.

We need to build an economy that creates enough work at fair wages for everyone. And we need to recapture our lost leisure. Those two aspirations can work together.

In a knowledge economy, our strength comes from the power of our ideas. And we are wired for those ideas and inspiration to hit in quiet moments of – leisure.

Psychologists John Kounios and Mark Beeman have mapped brain waves and found the “a-ha” moment comes in a calm, relaxed state, when we are doing anything BUT work – like when physicist Richard Feynman idly watched students goofing off spinning plates in the cafeteria and began making calculations of the wobbles, “for the fun of it,” which led to his developing the “Feynman diagrams” to explain quantum electrodynamics and ultimately resulted in his Nobel Prize.

Neuroscience is finding that when we are idle, in leisure, our brains are most active, the Default Mode Network lights up, which, like airport hubs, connect parts of our brain that don’t typically communicate. So a stray thought, a random memory, an image can combine in novel ways to produce novel ideas.

Anders Ericsson studied elite musicians at the Berlin Academy of Music and is credited with the now wildly popular notion that it takes 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to master anything. But the key that separated the truly great from the good and the adequate was the way they spent those 10,000 hours: they practiced intensely, first thing in the morning when they were freshest, for no more than 60 to 90 minutes at a time, and they rested more. In other words, like brain waves, like heart beats, they worked in short bursts and recovered in leisure and became excellent at what they did.

But perhaps the most compelling case for leisure is this: despite our overwork culture, we have a lot of butt-in-chair presenteeism, sick, unhappy, burned out and disengaged workers. We work long hours, but we do not necessarily work productive, efficient or creative hours.

Some years, international comparisons of GDP per hours worked have found, workers in Norway, Ireland, Denmark and even France, with their 30 days of paid vacation every year, their café culture, their generous paid family leave policies, their short work hours mandated by law and their new directive forbidding some employers from expecting workers to check work-related texts and emails after hours, beat us by a mile.

As we think about the next American economy, we need to consider policies, as well as cultural shifts, that respect that people need time, especially relaxed and personal time, every bit as much as they need money.

By dialing down on overwork, by once again matching wages, which have been stagnating, to productivity, which has been rising, we might not only be able to create more work for those who need it, and work smarter, but foster the creativity and innovation that will lead to a more dynamic, productive economy, and a better life.

After all, isn’t the pursuit of happiness part of what defines us as Americans?

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine