CNN’s Human to Hero series celebrates inspiration and achievement in sport. Click here for videos and features

Story highlights

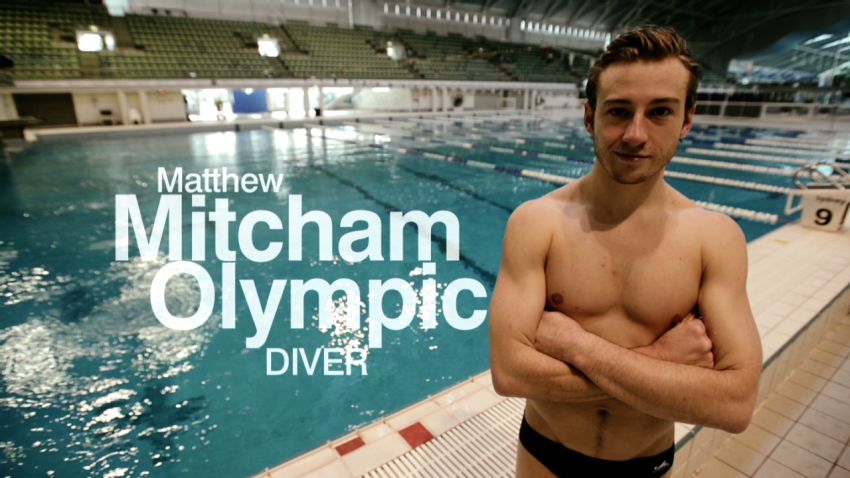

Matthew Mitcham was the first openly gay man to win Olympic gold medal

Australian struggled with depression after his diving success at Beijing in 2008

The 26-year-old has created a cabaret show of his life's highs and lows

He says this month's Commonwealth Games may be his final major competition

One minute he was at the top, looking down. King of all he surveyed.

The next thing he knew, the bottom had fallen out of his world – again.

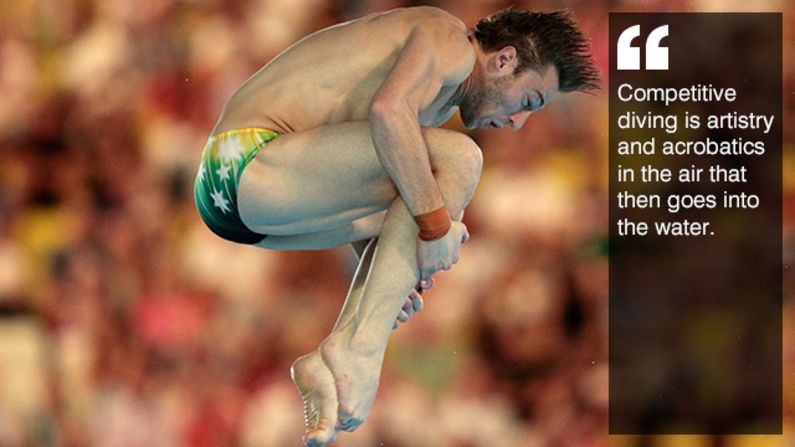

Diving is predictably a sport of highs and lows, but for Matthew Mitcham it goes so much deeper than that.

The first openly gay man to win an Olympic gold, he has learned to once again love the life that has contributed to his darkest moments.

“As a teenager, I felt like I dropped everything for diving. I put all my eggs in one basket because I felt like it was my ticket to being special,” the Australian tells CNN’s Human to Hero series.

And it did make him special.

Having made headlines around the world when he came out before the 2008 Beijing Games, his profile took a quantum leap when he shocked the home favorites and claimed the 10-meter platform title with a record single-dive score.

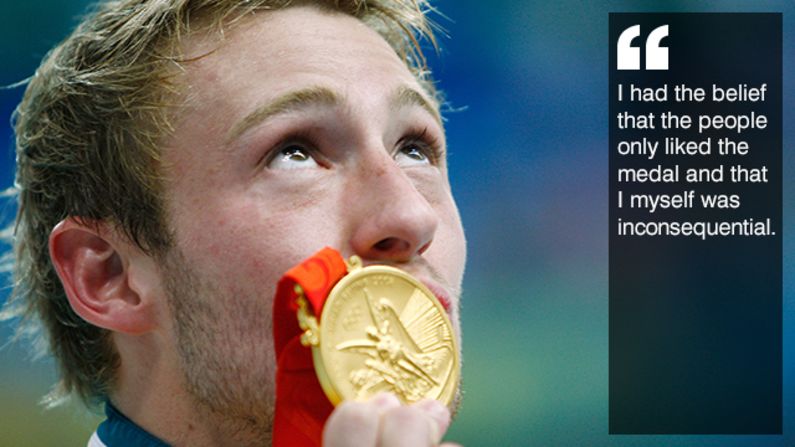

But that adulation – he was honored with his face on an Australian postage stamp – quickly turned to despair as he relapsed into the depths of the depression that had led him to retire two years earlier aged just 18.

“My self-esteem started to plummet again after Beijing,” he recalls, having been the first Australian diver to win Olympic gold since 1924.

“I had the belief that the people only liked the medal and that I myself was inconsequential.

“Diving has been a constant part of my life, but it hasn’t always been the most positive part of my life … but somehow I’m still here and I’m still doing it, so it has been an affair of highs and lows.”

Having overcome his well-documented personal problems – as laid bare in his book “Twists and Turns” – Mitcham is now heading into a new phase of his life.

Next week he begins what could be the last major competition of his diving career, the Commonwealth Games in Scotland.

He won four silver medals at Delhi four years ago, and is looking to complete a notable collection along with his Olympic and World Cup golds – especially after failing to reach the final in his 10m title defense at London 2012.

“There’s mixed feelings of excitement and a little bit of sadness because it might be time to move on,” the 26-year-old says.

“I’m not sure, I haven’t made any decisions but you know, getting older, looking at the rest of my life, I’m starting to consider that stuff now.”

When Mitcham triumphed at the Beijing Olympics, he was afforded the ultimate kudos by Australia’s LGBT community – being named “Chief of Parade” for the Mardi Gras festival in Sydney the following year.

“That was super cool,” he says. “I felt like Queen of the World.”

It appealed to the performer in him – and he has already started branching out into the entertainment world with a cabaret show based on his 2012 autobiography, which details his problems with drug addiction as he struggled to deal with his success.

He sings, plays the ukulele and recounts his life story.

“My dream when I grow up is to be famous and successful and, I don’t know, I want to dominate entertainment in Australia,” he says with a smile.

“I’ll start off small, I’ll start off in Australia and then the world. I want to be the next Oprah or the next Ellen Degeneres.”

These days, it is becoming more commonplace for athletes to be open about their sexuality – and when they do, it is almost certain they will spend a lot of time discussing their decision with the world’s media.

But back then, diving was leading the way out of the closet.

Four years before Mitcham, his compatriot Mathew Helm won silver in the 10m platform at Athens after announcing he was gay.

Four-time Olympic champion Greg Louganis was the most high profile, using the Oprah Winfrey show in 1995 to speak publicly about his sexuality and HIV status, albeit long after he had retired.

The American’s earlier book “Breaking the Surface” had provided inspiration for Mitcham ahead of his own life-defining moment.

“It made me feel like I had so much in common with Greg, so much more than I even thought I had initially,” he says.

“I’d never planned to come out before Beijing – it was never this big thing that I felt I had to get off my shoulders, I was just asked in an interview who I lived with and I just answered the question honestly.

“It ended up being a much bigger deal than I ever anticipated. The overwhelming support made me really proud to be able to be who I was and to achieve what I did as who I was.”

Born in Brisbane, and growing up in the suburb of Camp Hill, Mitcham’s first love was trampolining.

“When I was little, I just wanted to be the best in the world at something. It didn’t matter what it was, I just wanted to be the best,” he recalls.

He started trampolining aged nine, and was a world junior champion by 13.

Mitcham’s love of performing caught the eye of a diving coach at a public pool, as he was perfecting back flips off the springboards while the other kids were doing bombs.

“When I had to make the decision about whether I wanted to be a trampolinist or a diver, it wasn’t a heart decision, it was a head decision because trampolining wasn’t really established in the Olympics yet – there wasn’t much funding, there wasn’t as much opportunity for traveling, so I chose diving,” he recalls.

“My first experience of diving was a rush. I just wanted to try new things. The first time I got to jump off the 10m platform, I was totally fearless. It was fun. There was no fear whatsoever.”

No fear, maybe, but plenty of risk – with injuries a constant factor for top-level divers beyond the obvious, and potentially fatal, dangers of hitting your head on the apparatus.

Mitcham had to stop the 10m discipline at one stage due to repeated abominal-muscle tears – “it’s very fast, they’re very ballistic actions” – and has had spinal stress fractures.

“Even just hitting the water, you can dislocate shoulders,” he explains. “I’ve got six ganglions (cysts) on my left wrist and seven on my right wrist – just wear and tear.”

Mitcham credits his move to Sydney – Australia’s largest city – for reigniting his love of diving, having taken a year out.

It was there that he began training with coach Chava Sobrino, who had a major effect on his development both in and out of the pool.

“Chava was my first primary male-type father figure in my life because I didn’t meet my dad until I was 22,” he says.

“He was the first person who I had that respect for, who I trusted implicitly and who nurtured me.

“It’s important to have that kind of a relationship with your coach because, especially in a sport that has a lot of fear involved, where there’s a lot of the risk of the unknown, you have to have that implicit trust to know they’re not going to make you do something that you’re not ready to do.

“They’re not going to allow you to hurt yourself, so you do place a lot of faith in that one person.”

Mitcham pushes himself hard, training 10 sessions a week, each lasting 2-3 hours.

He was nursing a torn tendon in his elbow ahead of the Commonwealth Games, where his chief rival will be England’s 10m platform defending champion Tom Daley – another diver who has come out as gay.

Daley, a teen heart-throb who won the world title in 2009 at the age of 15, made his announcement on YouTube at the end of last year.

“I was as surprised as everyone else,” Mitcham says. “I’d even had dinner with him a month before it happened and I never knew anything.

“I totally understand with how young he is and, growing up in the public eye, it would’ve been extremely hard.

“I felt very fortunate that I didn’t get famous until after I had well and truly established my sexual identity, whereas he’s been in the spotlight since he was 13.

“It’s a really hard position to be in so I totally commend and support how he did it and when he did it.”

Mitcham’s compatriot Ian Thorpe is another to have recently come out. The Olympic swimming great had long denied rumors that he was gay, but this month told talk-show host Michael Parkinson he had been too afraid to admit it publicly.

Like Mitcham, Thorpe has also struggled with depression and substance abuse, and his attempt to return to top-level competition after retiring was unsuccessful.

“Sport can be pretty lonely sometimes when you focus everything on this one thing,” Mitcham says.

“Everything tends to fall by the wayside and that includes friends, support, social life … just fun, I guess. And when that one thing that your whole entire identity is wrapped up in goes with retirement, you probably get left feeling directionless because you don’t know who you are anymore.

“When it comes to actually medicating that depression, if you don’t have any better tools, I totally understand where the alcoholism comes from because I did the same thing.”

Mitcham says his depression started as young as 14.

“I saw it as a weakness and, especially in the world of sport, I thought I couldn’t be seen as weak. I had to have this facade of strength, so that shame really prevented me from reaching out and seeking any help,” he says.

“That eventually led me to retiring at 18 but when I moved to Sydney and started diving again, I was profoundly happy. I loved the environment I was in, I loved training with Chava and that ended up leading me to winning Beijing because I was just so happy diving.”

But that happiness wouldn’t last. Sometimes chasing a dream is easier than having realized it, as Mitcham would discover.

“I never actually addressed any of those underlying problems as a teenager. I felt kind of empty again, and directionless, and that depression that was lying dormant resurfaced and I fell straight back onto the last crutch that I used as a teenager to manage my feelings – and that was drugs,” he says.

“It wasn’t until I hit absolute rock bottom that I decided that I didn’t have all the answers and that I needed to ask someone for help. That was the start of my personal development journey of becoming a happier, healthier person.”