Editor’s Note: Editor’s note: This profile was first published in January 2011, when Judy Clarke was appointed to represent Arizona gunman Jared Lee Loughner. It has been updated.

Story highlights

Judy Clarke is considered the nation's foremost expert in defending capital cases

She has helped keep Susan Smith, Ted Kaczynski and Jared Loughner off death row

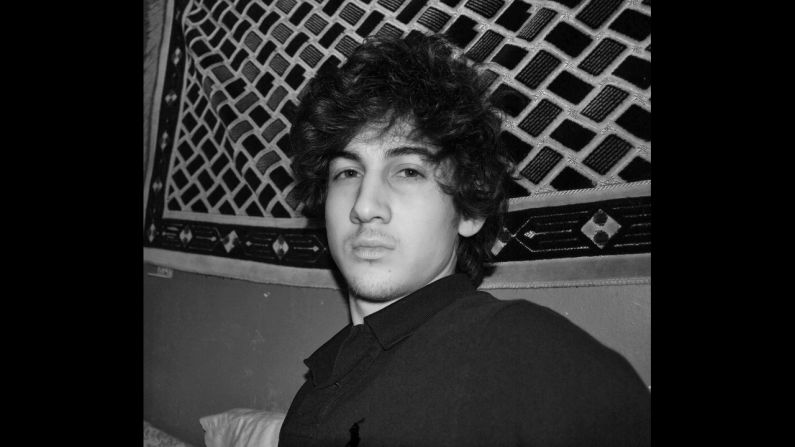

Clarke has been appointed to defend Boston Marathon bomb suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

Tsarnaev has been charged with using a weapon of mass destruction

One of the nation’s foremost experts on keeping clients off death row is joining Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s defense team.

Judy Clarke, a San Diego lawyer, has successfully fought for the lives of Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber; Jared Loughner, the gunman who killed a judge and wounded U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords; and other high-profile defendants.

In many of Clarke’s cases, a life sentence is a victory. She has made a specialty of defending people accused of the worst crimes imaginable.

There’s nothing flashy about Clarke, nothing to announce “here’s the high-profile criminal attorney” as she arrives in court to defend clients the rest of society loathes. She is, perhaps, the best defense lawyer you’ve never heard of.

A longtime colleague calls her lack of ego “almost freakish.”

Public defenders are the embodiment of a criminal justice system that believes everyone is innocent until proved guilty, that even people accused of horrific crimes deserve someone to stand up for them and find their humanity.

Many of Clarke’s colleagues believe she is the perfect lawyer for the job. David I. Bruck, a law school classmate and occasional legal colleague, spoke with CNN in January 2011, when she was appointed to defend Loughner.

“Judy is as genuine as a person can be,” Bruck said. “She explodes every myth about lawyers. She is motivated by a passion to stick up for the little guy, and there is nobody littler than a defendant accused of a horrendous crime who everybody wants to string up.”

Federal prosecutors have not decided whether to seek the death penalty against Tsarnaev. But few legal observers will be surprised if they do. Nor would they be surprised if the defense raises issues about Tsarnaev’s mental state.

“I’m glad she’s on the case. She’s a great lawyer,” said Quin Denvir, a former federal public defender from Sacramento, California. Denvir recruited Clarke to help him with the Kaczynski case.

“She’s a walking encyclopedia, she knows the law, and she has great empathy for the client,” he said. “She does it all.”

Laurie Levenson, a professor at Loyola Law School and a former federal prosecutor, said of Clarke, “She is familiar with the federal death penalty, insanity defenses, high-profile cases, and difficult clients.”

Clarke has no taste for designer clothes, sound bites or talking heads. In fact, she has absolutely no use for the media. As a public defender, she didn’t need publicity to hustle up paying clients. She was on a government salary, and there was no shortage of poor defendants.

For much of her 30-year career, Clarke ran the federal public defender offices in San Diego and in Spokane, Washington. In the mid-1990s, she became the first federal public defender to head the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

Now, even though she is in private practice, other public defenders seek her help on the tough cases. And so Clarke prefers to do her talking to judges, juries, other lawyers and law students.

Not surprisingly, Clarke did not return CNN’s calls for comment. But she spoke freely last year with the magazine at Washington and Lee University Law School, where she and her husband teach, as does Bruck.

She is a visiting professor, teaching third-year law students, and she articulated the philosophy that defines her as a defense lawyer:

“We stand between the power of the state and the individual, and in doing so defend the core values that make this country great,” Clarke said. “None of us, including those accused of a crime, wants to be defined by the worst moment, or the worst day of our lives.”

Colleagues say Clarke is highly effective. An ardent opponent of the death penalty, she has kept some of the nation’s most despised criminals – baby killers, bombers, white supremacists and terrorists – off death row.

You might know some of her clients by the public nicknames they acquired: the Unabomber, the Olympic Park bomber and the 20th hijacker.

Clarke is so relentless, her work ethic so formidable, that she often seems driven. But her ambition is not for herself, colleagues say. She believes in the system.

She was raised in Asheville, North Carolina, and graduated in 1974 from Furman College in Greenville, South Carolina. She received her law degree in 1977 from the University of South Carolina Law School, where Bruck was a couple of years ahead of her and served as a student adviser. Her talent was immediately apparent, he said.

Later, as a defense attorney in South Carolina, Bruck recruited Clarke to help him defend Susan Smith, the emotionally disturbed mother who in October 1994 strapped her two boys into her car and let it roll into a lake, drowning them. The defense argued that it was a failed suicide attempt.

It was Clarke’s first capital case.

“This is not a case about evil,” she told the jury as the trial began in state court during the summer of 1995. “This is a case about despair and sadness.”

Clarke didn’t argue insanity but brought her client’s abusive childhood and adult depression alive for the jury. She portrayed Smith as a woman so tormented by her failures in life that she even failed at her own suicide and jumped out of the car.

“She snapped, and Michael and Alex are gone,” Clarke told jurors. “Susan broke where many of us might bend.”

She let jurors feel Smith’s confusion and pain, and they took 2½ hours to convict Smith of murdering her sons. But they spared her life.

Afterward, the judge was so impressed with Clarke¹s work, he increased her pay to $83,000. She paid the taxes and donated the money to a nonprofit agency that defends the poor in capital cases.

State officials were not so impressed. They passed a law that prohibited out-of-state lawyers from working on South Carolina¹s death penalty cases. That law is still on the books, Bruck said.

We’ve been hit before on home soil

Clarke went on to join the defense teams in other high-profile capital cases in the federal courts. All were settled through plea bargains that took the death penalty off the table. Among them:

Ted Kaczynski: The mathematician known as the Unabomber pleaded guilty in January 1998 to making and transporting bomb materials that killed three people. Federal prosecutors in Sacramento, California, backed away from the death penalty after their own expert diagnosed him as a paranoid schizophrenic.

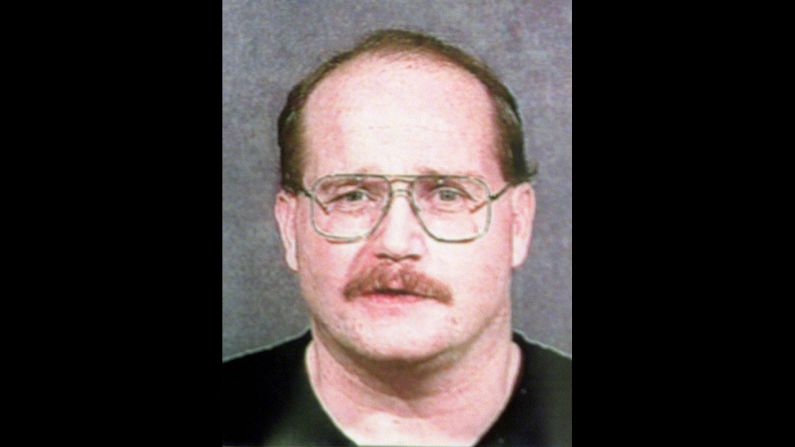

Buford O. Furrow: The Aryan Nations member pleaded guilty in 2001 and was sentenced to five life terms for a racially motivated shooting spree at a Los Angeles Jewish Community Center and the fatal shooting of a Filipino-American postal worker in 1999. Prosecutors dropped the death penalty when the defense documented and charted Furrow’s long history of psychiatric treatment for bipolar disorder. The decision later was criticized by the victims’ families.

Child shooting victims: What they’ve learned from the past

Eric Rudolph: The man known as the Olympic Park bomber pleaded guilty in 2005 to bombing a women’s clinic in Birmingham, Alabama, and other bombings, including at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. He was a survivalist and spent years on the FBI’s most wanted list. Prosecutors dropped the death penalty after Rudolph led them to several dynamite caches in the North Carolina woods.

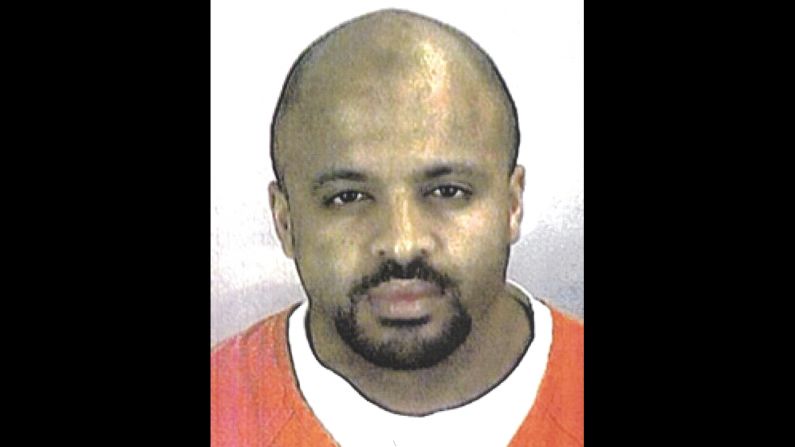

Zacarias Moussaoui: The 9/11 conspirator is sometimes referred to as the 20th hijacker. Clarke worked only briefly on this case. He repeatedly fired his lawyers and insisted on defending himself, abruptly pleading guilty to terror conspiracy charges in July 2002. His life was spared in 2006 when a lone juror held out against a death sentence after a trial punctuated by the defendant’s outbursts.

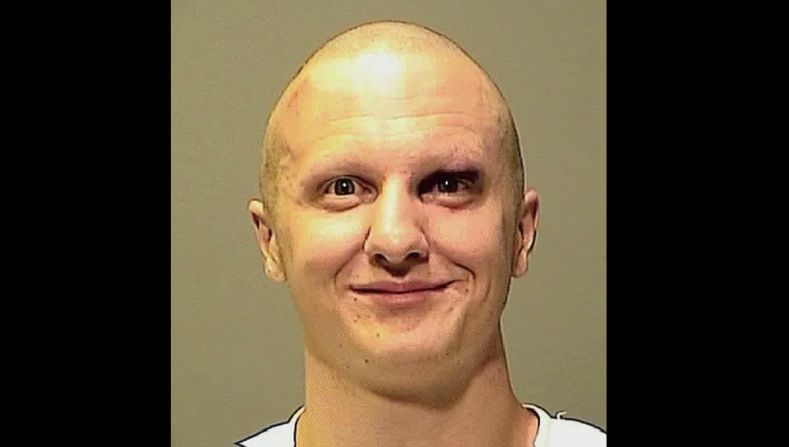

Jared Lee Loughner: The suspended community college student pleaded guilty to 19 murder and attempted murder counts in the Arizona shooting rampage that killed a federal judge and a 9-year-old girl and seriously wounded U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords. Two mental health experts diagnosed him as paranoid schizophrenic, and he was sentenced to life in prison under a plea bargain.