Story highlights

The FDA allows "compassionate use" drugs to save lives

Most denials come from drug companies, the FDA says

Some are taking a closer look at improving the program

'We all feel something has to change,' one executive says

At first, Sandy Barker decided to behave nicely and sit silently in the audience as an official from the Food and Drug Administration extolled the virtues of a program to get experimental drugs to desperately ill patients.

Then she couldn’t take it anymore. Barker’s hand shot up.

“I’ve been sitting here for the past hour trying to be quiet, but I want to tell you what happened to my son,” she said.

Barker looked down at a picture of Christian on her lap. She started to cry, but regained enough composure to describe how her son was diagnosed eight years ago with a rare form of leukemia when he was 13. A bone marrow transplant was supposed to help, but instead the donor’s cells attacked Christian’s body.

Christian’s graft-versus-host disease was quickly getting worse. His life was on the line. Nothing was working.

The Barkers searched for studies he could join but found none. Christian’s doctors desperately wanted to try an experimental drug, but first the FDA had to give its blessing.

The Barkers and their doctors begged the agency to allow Christian to use the medicine. By the time permission was given, more than three weeks had passed, and the graft-versus-host disease had moved to stage 4, the most severe stage.

Christian died two months later.

During a panel discussion at a conference on rare diseases, Barker says the FDA official noted it can be helpful to lobby one’s congressman to get access to experimental drugs.

She was stunned by that comment. She thought back to Christian’s final weeks on earth. As the disease ravaged his body, he bled and vomited constantly. Around the clock she changed her son’s bloody boxer shorts and bed sheets.

“My son was dying. He was hemorrhaging four liters of blood a day. When exactly was I supposed to call my congressman?” Barker told CNN.

The FDA program that allows patients to use experimental drugs is called “compassionate use.” Barker wonders, as do many others, if there might be a way to make it a little more compassionate.

‘The system works pretty well’

No FDA official at that meeting in February ever suggested that anyone should lobby their congressman to get access to a compassionate use drug, says Stephanie Yao, a spokeswoman for the agency.

Richard Klein, the director of the FDA’s patient liaison program who was on the panel at that meeting, told CNN he’s pleased with the compassionate use program.

“I think the system works pretty well the way it is,” he says.

Many would beg to differ.

After Dr. Darshak Sanghavi wrote a piece last year for the New York Times Sunday magazine about compassionate use, he was “heartbroken” to receive desperate e-mails seeking his advice on how to navigate the program.

“Their stories were really sad,” he says. “There’s clearly a need for some sort of an improved process.”

Sanghavi, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, is convening a closed-door meeting later this month that will include senior pharmaceutical executives, a patient advocate, an ethicist and a lawyer at Harvard, and Mark McClellan, the former commissioner of the FDA.

Many drug company executives agree that the system is deeply flawed. A main complaint is when patients take to social media and make very public campaigns to get the drugs they want.

Last month the parents of a 7-year-old boy did just that and made headlines around the world. Josh Hardy’s parents took to Twitter and Facebook when the drug company Chimerix denied their request for an experimental antiviral drug to save Josh’s life. After receiving death threats from “Josh’s army” – executives had to hire security guards – Chimerix reversed its position and granted Josh and other patients like him access to the drug.

Now that he’s had the medicine, the virus that nearly killed Josh is gone and he’s been moved out of the intensive care unit.

In light of that case, a biotechnology industry group, BIO, has decided to take another look at the issue, says Sara Radcliffe, BIO executive vice president.

“The situation in which people make pleas on social media standing by the child’s bedside, wondering what’s going to happen tomorrow, is a horrible, horrible situation,” says a senior source in the biotechnology industry, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the situation.

“We should be doing better than that,” the source added. “We all feel something has to change.”

But the question is – what?

‘It’s absolutely something we would think about’

FDA officials say that since 2009 they’ve approved more than 99% of requests for compassionate use drugs. Denials have come almost completely from the drug companies themselves.

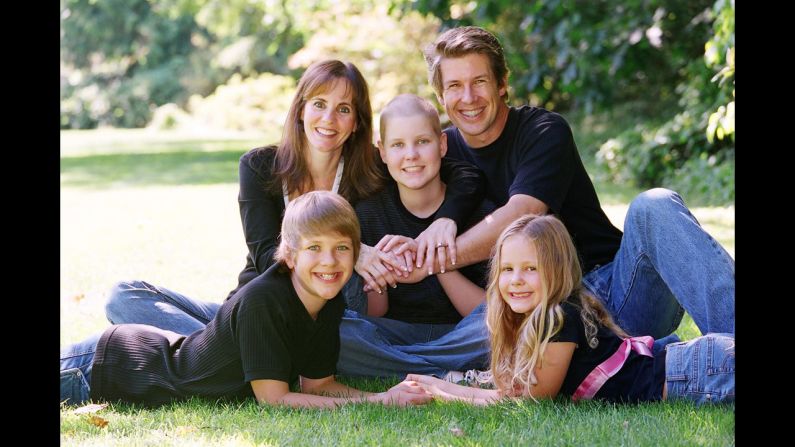

Nathan Traller knows this all too well. His daughter Nathalie, 15, has a rare cancer called alveolar soft part sarcoma and has tried and failed every available treatment. The cancer, which started in her brain, is now in in Nathalie’s pancreas, lungs, abdomen, intestines and bones.

“It really couldn’t get much more widespread,” her father says.

The Trallers reached out to three drug companies asking for use of their experimental cancer drugs. All three said no.

Two of the companies, Merck and Bristol-Myers Squibb, declined to discuss Nathalie’s case with CNN.

Bristol-Myers Squibb issued a statement about patients in general who have no other treatment options. “It is exactly with those patients in mind that, through regulatory approval, we work to ensure broad access to our medicines as quickly as possible, while also remaining mindful of protecting patient safety.”

CNN spoke with a representative of Genentech, the manufacturer of anti-PDL1, the drug Nathalie was denied.

“It really comes down to the fact that we don’t have drug supply,” Krysta Pellegrino said. “Should we have additional supply in the future, it’s absolutely something we would think about.”

Can’t they make more of the drug?

Not right now, Pellegrino answered.

Why not?

Because Nathalie isn’t the only person who’s asked for anti-PDL1, she explained. In the past year, Genentech has received about 100 requests.

Genentech made enough of the medicine for the 350 people who have been involved in clinical trials – would making more be too expensive?

It’s not a matter of money, Pellegrino said. It’s that anti-PDL1 is complicated to make, and Genentech has limited manufacturing capacity.

“Would we have to, just for example, not manufacture Herceptin in order to manufacture this?” Pellegrino said, naming Genentech’s blockbuster breast cancer drug.

Is she saying that if Genetech made anti-PDL1 for Nathalie and patients like her, some breast cancer patients wouldn’t get their Herceptin?

No, Pellegrino answered, not necessarily.

So what is she saying?

“We don’t have current supply at this time to consider opening a compassionate use program,” she repeated.

Later, Pellegrino sent an e-mail saying that “making additional anti-PDL1 at this time would mean not being able to make other medicines, including those for people with breast, colon and lung cancers, and investigational medicines being studied for Alzheimer’s and other diseases.”

Like making cupcakes

Vickie Buenger isn’t quite buying it.

Sure, supply might sometimes be an issue, especially for smaller pharmaceutical companies, she says. But in some cases the lack-of-supply argument, which is frequently used by drug companies, “falls short a bit.”

Buenger’s 11-year-old daughter died of cancer five years ago, and since then she formed the Coalition Against Childhood Cancer and helps advise parents seeking compassionate use.

Buenger, who teaches at Texas A&M University with a joint appointment at Mays Business School and the professional program in biotechnology, understands that as currently configured, perhaps production lines really can’t satisfy compassionate use requests. But could that be changed?

“It’s like making cupcakes. You can only make 12 at a time because the pan only holds 12. But that doesn’t mean you can’t make more than 12. You just have to change the way you’ve set up the situation,” she says.

She and other observers think there may be different reasons why drug companies often say no to compassionate use.

First, compassionate use patients can’t be counted as study subjects, so they don’t contribute to the clinical trials that need to be done to get a drug on the market.

Second, compassionate use patients are very, very sick and have failed at multiple treatments. They could very well fail on the experimental drug, too. Companies fear that a death – especially if it’s a child – could turn the public and the FDA against them.

Drug industry executives dispute this second point. They say they often grant compassionate use to extremely sick patients, although they won’t say how many requests they deny and how many they allow.

But they do agree that servicing compassionate use requests in general can divert them from their goal, which is to get the drug on the market where it can help anyone who needs it.

“Companies have an ethical obligation to develop drugs and biologics for patient populations and bring them to market as fast as possible,” BIO writes on its web page about compassionate use, underlining the sentence for emphasis.

Like frat brothers crashing a wedding

Nathan Traller, Nathalie’s father, has spent a good part of the last seven months on the phone with pharmaceutical executives trying to convince them to let his daughter try their experimental drugs.

He thinks Buenger is right – drug companies view compassionate use patients like Nathalie as a distraction, as something that sidetracks them from their real work.

“We’re just a pain to them. That’s really the landscape,” he says.

He wonders if there might be some way to reform compassionate use so the drug companies benefit, too. Is there a way to make it a win-win for the patient and the company?

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim doesn’t have an answer, but he thinks he might have a path.

Kesselheim, an internist and ethicist at Harvard Medical School who’s been invited to the Brookings meeting later this month, says the FDA should think about ways to tweak the system so that information gleaned from compassionate use patients might help a drug company’s application to market a new drug.

In the end, that’s what ended up working in the Josh Hardy situation. After the outcry on social media, the FDA agreed to allow Josh Hardy and other patients like him to become study subjects. Josh won, and so did Chimerix.

Kesselheim offers this simile: A drug company wants to make just enough medicine for its clinical trials and not much more, just as a wedding caterer wants to make just enough food for the guests and not much more.

While he doesn’t want to insult compassionate use patients, in this story they are fraternity brothers crashing a wedding.

“Let’s say 200 people are supposed to show up at a wedding, and on the day of the wedding the groom’s 50 frat brothers show up and want dinner. They can’t get it because the caterer didn’t make 250 pieces of fish,” he says.

“But let’s say there was a national policy that all wedding caterers had to plan for frat brothers crashing weddings. Then caterers would build it into their plans to accommodate 50 extra guests. They would build it into their costs,” he adds.

Any requirements about feeding fraternity brothers would be across the board, so no one caterer would get an advantage. The same would be true for drug companies supplying medicine to compassionate use patients.

“It might make them less skittish about making drugs available if they all had the same set of rules,” Kesselheim says.

And who knows? Just as those fraternity brothers might add something to the party instead of just disturbing it, the compassionate use patients might just add something to the company’s FDA application instead of just bogging it down.

That’s what Nathalie’s father wants.

“I’m not trying to divert the whole system to benefit my daughter,” he says. “All I’m saying is, look at the system now. Is this really the best we can conceive of? It’s really a head-scratcher to me, and I’m sure it’s probably a head-scratcher to other people, too.”

In cancer drug battle, both sides appeal to ethics

CNN’s William Hudson contributed to this report.