Story highlights

Couples in Japan are "graduating from marriage" -- sotsukon -- to fulfill their individual dreams in retirement

Due to a declining birth rate and long life expectancy, the longest period in a woman's life is now after her children have left home

The trend reflects a growing individualization of the family in Japan

When Yuriko Nishi’s three grown-up sons left home, she asked her husband of 36 years an unusual question: Was there any dream married life had prevented him from fulfilling?

“We started wondering what path should we be walking on,” says Nishi, 66. “We told our children it was a good chance to evolve our family.”

Like many others in Japan, the couple decided to graduate from marriage – or “sotsukon.”

This was not divorce.

Sotsukon is for couples still in love, who decide to “live apart together” in their sunset years to achieve their separate dreams.

In a nation with an aging population, the idea has taken root.

Living apart together

Yoshihide Ito, 63, after working for decades as a cameraman in Tokyo, told his wife he wanted to escape city life and return to his home prefecture of Mie, in southern Japan, to become a rice farmer.

Nishi wished to continue her career as a fashion stylist in the capital.

“He visits me once a month. I visit him for a week at a time, too,” Nishi says.

Distance, she explains, helps the couple to miss and appreciate each other; they now plan date nights for the time they spend together.

“Our marriage is in good shape. We share two totally different lifestyles.”

Graduating from marriage

The term “sotsukon” was coined in 2004 by Japanese author Yumiko Sugiyama in her book “Sotsukon no Susume” – “Recommending the Graduation from Marriage.”

The word is a commingle of “sotsugo” (graduation) and “kekkon” (marriage).

“In Japan, traditionally the man is the head of the household, and the wife lives under his financial support as a domestic worker,” says Sugiyama.

“I wondered what if each member of the married couple could obtain more freedom to do what they want without getting divorced?”

The imagination of the Japanese public was captured – particularly that of the housewife – at a point when changing demographics in the nation were reshaping society.

Just one million babies were born in Japan in 2014, according to government figures. That tally is the lowest figure on record in the Asian nation.

Furthermore, Japanese women in the same year had the longest life expectancy in the world – 86.83 years – according to the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry.

“That means the longest period in a woman’s life is after her kids have gone,” says Masako Ishii-Kuntz, a professor of sociology at Ochanomizu University, in Tokyo. “Many empty-nesters have nothing left to do but care for their husband.

“They realized they should pursue their own hobbies and happiness.”

Dream catchers

On a rainy April evening, Kazumi Yamamoto is delivering her fortnightly sotsukon seminar to a group of women aged between 30 and 60 years old.

She advises the wives on how to persuade their husbands to agree to sotsukon.

Yamamoto, who graduated from marriage one year ago, moving from Hiroshima to open a beauty clinic in Tokyo – a life-long ambition – says it is women who usually suggest sotsukon.

Husbands, Ito says, can be intimidated by the concept.

“Men ask me, ‘What have you eaten [since sotsukon]? It must be so hard doing domestic jobs by yourself.’

“I think men who deny their wives sotsukon have been living a self-centered existence.”

At her seminars Yamamoto hears various reasons for women seeking sotsukon.

“Me and my husband don’t have much to say to each other, and he thinks I’m his maid,” says one woman, aged 56. “But I don’t want to divorce or I might feel lonely when my health becomes weaker.”

“My husband wants to return to his hometown to take care of his parents, but I don’t want to go,” says another woman. “I would like to travel and spend more time with my friends.”

Celebrity endorsement

In recent years, celebrity endorsement has pushed sotsukon deeper into the mainstream.

Most famously, in 2013, Japanese comedian Akira Shimizu and his wife announced they would graduate from marriage, and published a book “Sotsukon – A New Form of Love.”

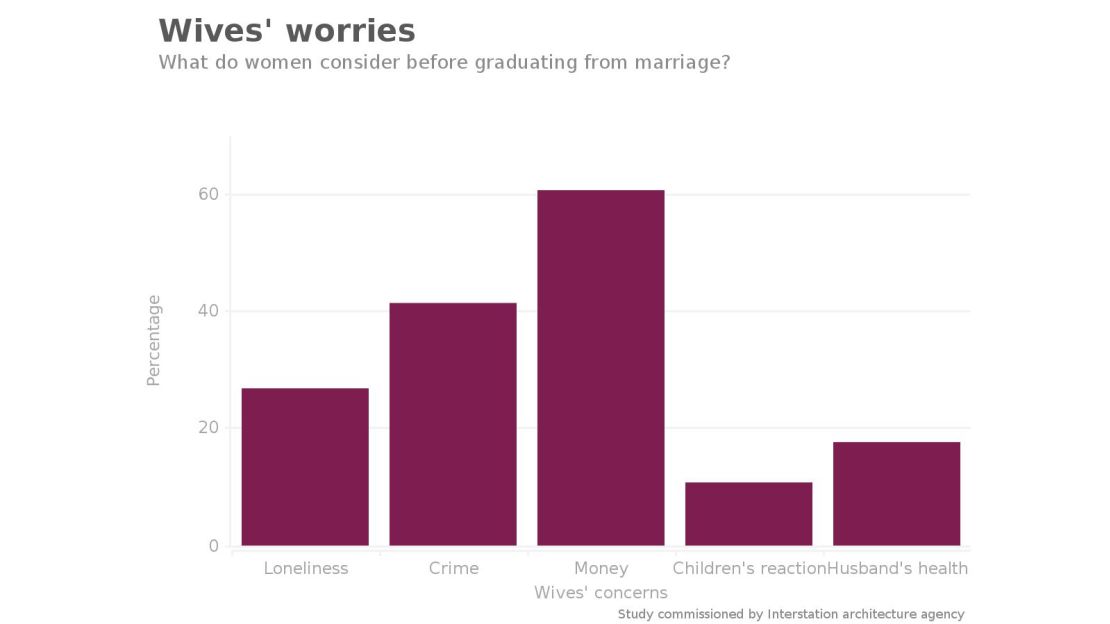

While there are no official figures on how many couples in Japan have followed this path, a 2014 survey commissioned by Interstation architecture agency in Tokyo found a widespread desire to do so.

Of the 200 married women polled, aged between 30 and 65 years old, 56.8% said they eventually wanted to graduate from marriage.

Retirement was the period of life most women identified as the ideal point to undertake sotsukon.

Be nice to your wife

Husbands in Japan, generally speaking, have had something of a wake-up call over the past decade.

A groundbreaking law passed in 2007 allowed a divorcing wife for the first time to claim as much as half of her husband’s pension.

It prompted widespread predictions of a spike in divorce rates in Japan. In Tokyo, The National Chauvinistic Husbands Association – formerly an unrepentant group of boisterous salary men – began devising strategies to avoid divorce: listening to and respecting their wives was one tactic. Helping with the housework was another.

More recently, Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe has made women entering – and remaining in – the workforce a pillar of his economic policy. “Abenomics is womeneconmics,” he declared at the World Assembly for Women in Tokyo last August.

In 2014, 64% of women aged 15 to 64 in Japan were working, compared to 46% in 1969.

“More Japanese women are now at work and therefore receiving pensions,” says Ishii-Kuntz. “The wife knows she can make her own living.”

To Ito, this is important.

“I don’t know if we can really call it sotsukon if the wife’s lifestyle is being paid for by the husband,” he says. “Wives need to be financially independent to truly graduate from marriage.”

Individualization of the family

The Japanese family as a whole is changing, says Ishii-Kuntz.

“Family members have become more individualized. Each family member is allowed to seek whatever he or she wants, rather than spending all their lives taking care of family members,” she says.

Multiple generations of adults living in one household is becoming increasingly rare in Japan, she adds. Furthermore, it is not unusual for husband and wife to sleep in separate beds in the same room.

Perhaps sotsukon is the ultimate climax of that individualization.

Graduating from the traditional strictures of marriage, however, does not have to translate into an end of intimacy or loss of love.

Nishi smiles: “After having lived apart, I cherish him more. If I marry again, I want to marry him.”