Day five at sea in the High Arctic, and the news breaks early in the day. At 6 a.m, we’re officially the most northerly vessel on the planet, reaching 81 degrees 16 minutes latitude. Not bad in a world of 7.3 billion people.

I’m on the deck of the MS Expedition ship as it hugs the most northerly multiyear sea ice, formed over millennia, just 524 nautical miles from the North Pole.

On into the horizon, blinding white ice floes flood the Arctic Ocean – chips of huge glaciers and weaker seasonal ice.

The ship is engulfed by glaring blue and white, as sea ice and sky merge with dizzying reflections. Standing on the polar seascape, vast and mesmerizing, feels far removed from human civilization. Feral and raw, the untamed extreme beauty of polar desert is the reason I am here, where the -5 C (23 F) biting chill sets in fast.

Our ship is manned by a specialist polar crew from G Adventures, a tour operator with a big focus on sustainability and conservation.

Through charity projects and an on-board team of geologists, naturalists and scientists, the journey is aimed at spotlighting the challenges that face the fragile region. Visitors are expected to make an actual difference and leave knowing exactly how to contribute to conservation.

Warning bells

Small enough to get into the narrow ice corridors and up close to glaciers, the MS Expedition’s strengthened hull crunches loudly through slabs of centuries-aged snowcaps and icebergs.

The frozen landscape shelters rare beluga, blue and bowhead whales, snoozing bearded seals and carries tracks of a hunting polar bear.

As we sail on, another first is marked. We become the first vessel of the year to circumnavigate Spitsbergen, the largest island in Norwegian Arctic territory, due to receding ice allowing passageway. Behind this celebration are warning bells.

As one of the most fragile environments in the world, global climate change discussion pivots on the Arctic, with world leaders steering its fate.

In 2015, the United States granted permission to petrochemical giant Shell to drill the Arctic seabed for oil.

Although drilling was abandoned due to high costs and lack of findings, the company is seeking to extend exploration leases that currently expire in 2017. With oil prices in constant flux and demand usually rising, it could only be a matter of time before the Arctic is viewed as a viable target.

In 2015, the multiyear ice has receded far north, allowing us to press deeper into the Arctic than expected.

It’s “an indisputable aspect of human-driven climate change,” declares Jamie Watts, ship leader and marine life enthusiast.

Photos: Alaska as it’s rarely seen

Record ice melts

Multiyear ice nourishes the entire Arctic food web. Its decline, said to be a result of greenhouse gas emissions, has drawn polar bears farther from their dens onto thin broken ice – feeble hunting ground.

Increasing global carbon emissions and greenhouse gases are said to be propelling a colossal decline in multiyear ice.

In 2015, Arctic ice cover fell to the fourth lowest extent in the satellite record, with temperatures hitting the second highest recorded, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

“Ten years ago this would have been an astonishing summer of ice melt,” says Ted Scambos, NSIDC’s lead scientist. “Now it is just another season in a decade of low years.”

Climate models predict Arctic summer ice will eventually disappear. The survival of marine life is entirely reliant on the shelter, nutrient-density and protection of multiyear sea ice.

“The almost complete melt-away of the multi-year ice in recent summers has really knocked the core productivity of the whole ecosystem,” Watts warns.

For would-be adventurers to these reaches it means intensified scouring for polar bears and Arctic wildlife – and coordinated round-the-clock watch duties for our guides.

Northern Lights: 11 best places to see the aurora borealis

Uncharted waters

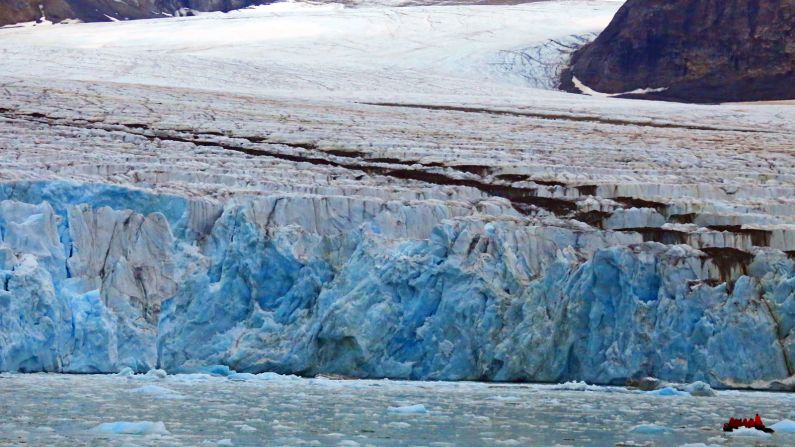

After passing over the crest of Spitsbergen, we navigate the colder, icier eastern front. Here, serene fjords give way to ice-encrusted mountains, as gigantic glaciers tumble into the frozen glassy sea.

From the ship, I’m bundled onto a small inflatable raft to get up close. Traversing uncharted icy waters, the stillness is staggering.

Engine off, we drift between surging blue icebergs the size of houses and glide up to centuries-layered glaciers the size of cities. Our tiny boat feels insignificant in this hyper-frozen other-world.

The midnight sun casts a golden glow, hovering just above the horizon as it struggles to climb the earth’s curvature at this latitude.

In a rare stream of sunlight, crystalline glaciers and translucent icicles glisten like diamonds, as we float silently past.

Surrounding mountains reveal silvered flashes of spirited Arctic foxes, awaiting the failed first flight of fledgling guillemots. Nearby, kittiwakes flood towering limestone cliffs that resemble something out of “Jurassic Park.”

And the elusive polar bear makes an appearance. A herd of blubbery and pungent walruses lines one side of beach while, opposite, a lone plump bear navigates ice and mossy mountainside. He’s a striking animal, thick cream fur contrasting against dark shale and the frosted backdrop.

The bear is guided by a superior sense of smell, as he visibly follows his nose towards his prey, which he can smell more than a kilometer away.

Arctic lifeline

As the largest mammals in the world to actively hunt humans as food, proximity to bears involves firearm-trained guides.

We watch from small boats, a distance from the shoreline. A steady decline in bear sizes and birth weights has been linked to Arctic warming. It’s unavoidable, explains Susan Adie, wildlife activist and G Adventures operations manager.

“We are going to see more scrawny bears in the long term, directly linked to a loss of sea ice,” she says.

The ice is a lifeline for Arctic wildlife.

Polar bears are the star attraction but can quickly become sidelined.

While observing a mother and bear cub nuzzling on land, our attention is diverted by a shoal of white beluga whales silently somersaulting past our boats, gray babies in tow.

These dynamic masters of the Arctic Ocean rely on peaceful and remote Arctic seas to communicate. Noise and pollution from Arctic drilling and submarine explosions (for oil exploration) could exact a devastating marine toll, Adie explains.

“Agreeing to Arctic drilling is a bad decision and a mistake. The problems are so huge and complicated.”

She adds, “Bowhead whales have carved an evolutionary pathway for migration and feeding. Drilling would force them to attempt new dangerous routes.”

Brink of meltdown

“If the young are endangered, the species becomes threatened. This is just one example.”

Threats of potential oil spill could be fatal for the fragile Arctic environment, already teetering on the brink of meltdown.

For my fellow passengers, including travelers from Brazil and China, visiting the Arctic demands responsibility. Landings are punctuated by lectures from chief field researchers.

They’re united in the belief that welcoming and educating visitors to the region will help preserve its future.

Watts sums it up. “You have to see it, to feel it with your own senses. We only want those who are engaged enough to genuinely do something about looking after it.”

For now, a major environmental battle has been won, with one oil giant abandoning operations, but with future prospecting still on the table the war over the Arctic is far from over.

The possibility that future generations may not witness centuries-aged ice, the wildlife it sustains, and the serenity of the hyper-frozen scene would be a great tragedy of our time.

Anisha Shah is a journalist and photographer, specializing in emerging destinations travel, from Mozambique to Myanmar. After six years as a BBC radio and TV journalist, she is now freelance and has been published across media outlets including CNN, Africa Geographic and Huffington Post. Tweet her @anishahbbc