In the past three years Special Agent Brenton Easter has personally identified smugglers, disrupted the black market for antiquities and recovered more than 2,500 stolen cultural artifacts worth about $250 million.

All of this has earned him comparisons to a certain bullwhip-toting movie character.

“I always wanted to be like Indiana Jones and I guess I’m lucky enough to now be able to say I kind of am a little bit like him,” said Easter, who works for the Cultural Property, Art, and Antiquities unit of Homeland Security Investigations, a branch of the Department of Homeland Security.

“I think that I’ve probably dressed as Indiana Jones for Halloween non-stop for about the last 30 years or so. Now, I not only dress myself, but I dress my children as Indiana Jones. So it’s been something that’s dear to my heart since I was a child.”

Easter and his team are locked in a constant game of cat and mouse with criminals who are trying to smuggle artifacts into the U.S. His goal is to return looted artifacts to their home countries and disrupt the networks smuggling them. Whether it’s the return of dinosaur skeletons to Mongolia or the repatriation of stolen Holocaust art, “pretty much anything that can pop into your mind as belonging to one particular culture, that’s what we would investigate,” Easter said.

For the last decade, Easter has developed an expertise in the cultural properties black market. His unit has rapidly expanded its databases, mapped smuggling routes and tracked thousands of looted artifacts being sold and traded all around the world.

“There are, unfortunately, more pieces than I’d like to think of that we’re actively trying to recover,” he said.

‘Finding facts’

Easter and his team say they have returned more than 8,000 items of cultural significance to a home country or village. But the unit also has evolved its mission in recent years to disrupting the black market antiquities trade through criminal prosecutions.

“These criminal prosecutions are very, very hard to make,” Easter says. “One of the reasons they are so hard to make is because you have to often times prove knowledge in these cases that somebody knew that a piece was stolen. You need a lot of facts and a lot of evidence to show what someone’s thinking. And that’s why I allude to that quote .. where (Indiana Jones) says, ‘archeology is not about finding truth, it’s about finding facts,’ so that’s kind of what were faced with, that same dilemma.”

While its not uncommon for looted property to eventually make its way to legitimate museums or auction houses or be sold by dealers who are unaware dubious origin, Easter and his team have identified a number of suspected career smugglers that they are investigating and building cases against.

“There are definitely some people that are continuously dealing in stolen or illicit cultural properties. Some of those people I know exactly who they are. I know exactly where they are,” Easter said. “Unfortunately, we haven’t been able to get them yet but down the road we will.”

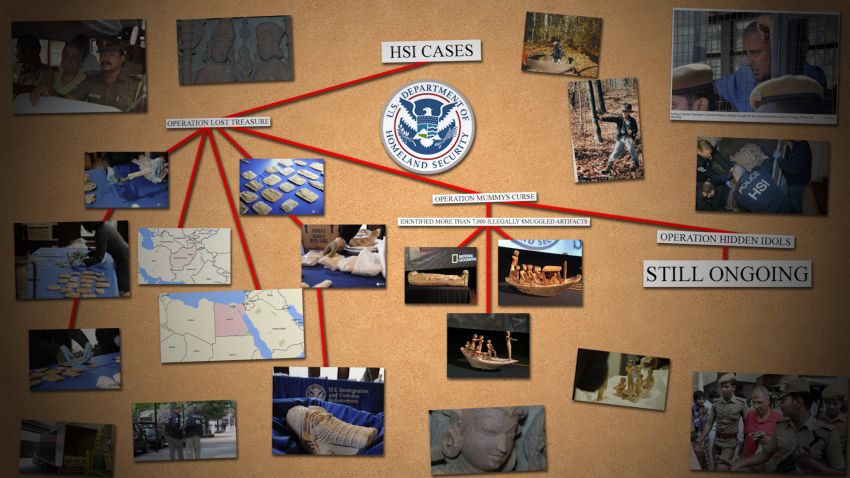

Operation Lost Treasure

One of those men, Subhash Kapoor, owned a New York gallery called Art of the Past on Madison Avenue. Kapoor was found to be in possession of more than 2,600 artifacts worth more than $100 million, almost all of which were allegedly stolen out of unguarded temples and shrines from remote Indian villages and archeological sites. After a four-year investigation with officials in India, where HSI Investigations has one of its 46 international offices, Kapoor landed in Indian custody and is awaiting trial on charges of receiving stolen artifacts. Four of his alleged co-conspirators are facing charges in the U.S.

This evolution in combating the looters and dealers began with a case dubbed “Operation Lost Treasure,” which began after Easter and his colleagues identified an organization out of Dubai that was obtaining and selling stolen artifacts from Iraq, Egypt, Libya, Turkey, and elsewhere in the region. As the case progressed, it was revealed the same organization was also dealing in antiquities stolen from museums in Western Europe.

“They then would hit these smuggling networks to distribute these pieces to your normal violators. And so that case was successful because we did a quite of bit of disruption, we did seize quite a few materials, we did a bunch of repatriations, and we did have some criminal prosecutions there too,” Easter said.

The investigation eventually led to the seizing and return of a large stolen Assyrian statue, the head of King Sargon, to a museum in Iraq. Easter saw it as a symbolic victory given the state of the Mideast and reports of ISIS pillaging ancient sites all over Iraq.

“One of the things you could call these are conflict antiquities,” Easter said. “It was phenomenal to be able to give something back to that newly reopened museum, especially during the horrible turmoil that they are facing and after having the destruction of similar pieces in their country. To know that they have this piece back safely, that’s gratifying.”

Related: Group says ISIS beheads antiquities expert

It was during “Operation Lost Treasure” that Easter and his team began to notice that ISIS and other linked terror groups were not just in the business of destroying cultural artifacts, but that they were obtaining money from the sale of illicit cultural properties.

“We saw networks that were operating in these conflict regions prior to ISIS and we can tell you with certainty those networks are still operating today and that pieces are still coming out of those regions via some of the traditional networks and paths that we saw before,” Easter says. “We are targeting those networks, we are creating those databases that when those pieces do hit the market, we’ll be able to intercept them and go after these people criminally.”

Focusing on the Middle East

Easter and his team now are focusing more of their attention on the Middle East as continued turmoil in Iraq and Syria paves the way for looters, smugglers, and dealers to stock their inventory of cultural artifacts.

“What were working on right now as part of ‘Operation Fertile Crescent’ is developing a database of stuff that may be coming out of these conflict zones in the Middle East,” he says. “What the people are doing now, fleeing Syria … also creates an opportunity for these cultural property smugglers to move stuff out of Syria and conflict zones into other places where they might be able to sell these items. All of these crimes tend to go hand in hand.”

When an artifact is stolen from a conflict zone, it only takes a few years of being exhibited in museums or galleries before buyers are satisfied that it came from a legitimate source, according to Easter. So when an item is taken from the ground or out of a temple, Easter and his team are prepared to wait out the “cooling off” period that looters use to build an air of legitimacy before putting it on the market where it can be intercepted.

Over the last ten years Easter has seen his unit grow from one or two agents to an entire team devoted to investigating what Interpol estimated in 2014 to be a $9 billion illicit industry.

“Our agency could probably be seizing something on a very regular basis – if not close to every week, everyday – but that’s not the goal anymore. The goal is not to seize and repatriate,” Easter said. “What we’re first and foremost trying to do is disrupt and dismantle these criminal organizations. And going after them is really where you’ll hopefully stop these crimes, make connections to other crimes, and make more of a difference, catch the bad guys.”

Indiana Jones himself would be proud.