Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for The Miami Herald and World Politics Review, and a former CNN producer and correspondent. Follow her @FridaGhitis. The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.

Story highlights

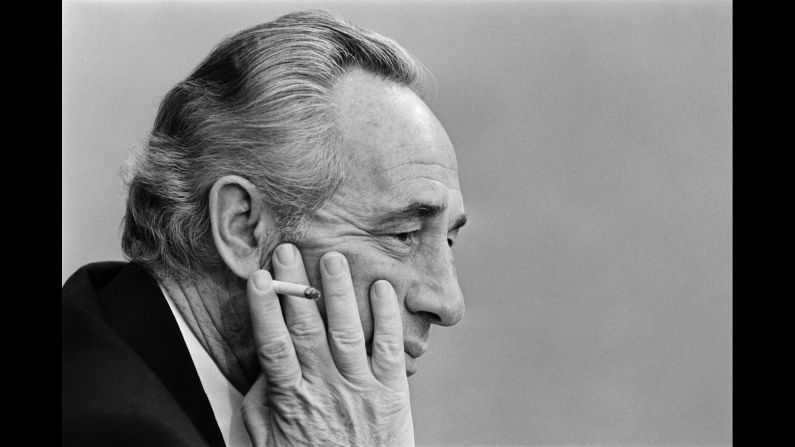

Frida Ghitis: Despite his poor performance at the polls, Shimon Peres became a beloved national figure

But many fear that what Peres stood for may die with him, Ghitis writes

There’s something different about the way the world is mourning the death of former Israeli President Shimon Peres.

What we’re hearing is not simply the usual goodbyes to a man with a longstanding high profile on the global stage. No, this time there seems to be something else going on. Grief is being expressed not just for Peres, but for what he represented.

Simply put, there seems to be a sadness, tinged with fear, that what Shimon Peres stood for may die with him.

If you want to understand what Peres embodied, it helps to know what an uncommon, seemingly contradictory person he was: a practical dreamer, a realistic visionary, a hawk-turned-dove, a man who believed in strength as a means to peace, and someone who worked until the very end of his life to achieve his goal of bringing peace to the Middle East.

This is not a view embraced by everyone. There are many Arabs, in particular, who view his legacy as grievously dark and negative. They look at his early support for Israeli settlements (although he was later critical of them) and his pivotal role in building Israel’s military. Perhaps more than anything, they recall some of the most controversial actions of the Israeli Defense Forces under his government.

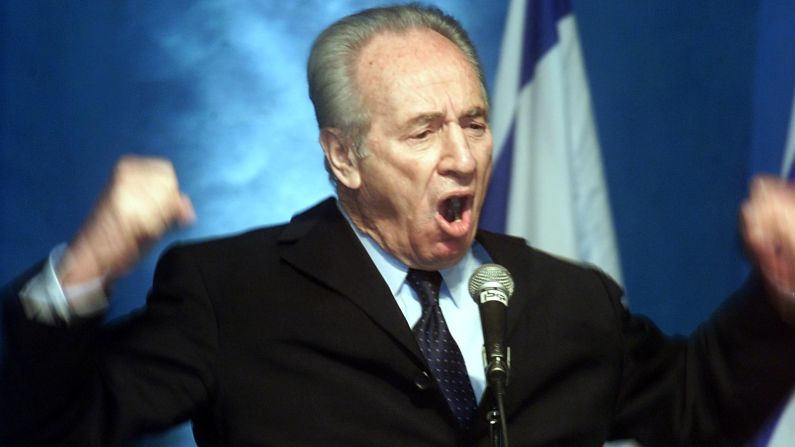

But the larger reality – and the reason why so many world leaders, including President Barack Obama, are attending his funeral on Friday – is that Shimon Peres came to personify the most scarce of all qualities in the Middle East: optimism about the prospects for reconciliation and a relentless determination to make it happen.

Peres often spoke of his most cherished goal like a man convinced he can see the future. “The Palestinians are our closest neighbors,” he reportedly declared, “I am sure they can become our closest friends.”

One man who knew him well, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, tweeted “Shimon Peres’ death is a heavy loss for all humanity and for peace in the region.” Haaretz reported that Abbas called him a partner in making “the peace of the brave.”

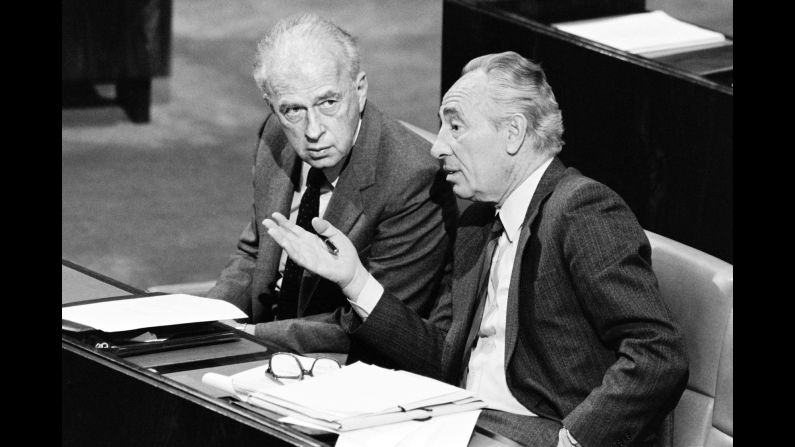

The peace of the brave was shorthand for the Oslo Accords signed on the White House lawn in 1993, which earned a Nobel Peace Prize for Peres, along with then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. The reconciliation that was supposed to follow never quite materialized. But Peres never gave up trying to make it happen.

World leaders are traveling to Israel for his funeral on Friday. Their presence in Jerusalem is partly about paying their respects, but perhaps also meant to convey their wish that the vision outlive the visionary. Certainly, it is a way of telling the world, of telling Israelis and Palestinians, to not give up on peace.

President Obama wrote, “There are few people who we share this world with who change the course of human history … they expand our moral imagination and force us to expect more of ourselves. My friend Shimon was one of those people.” Obama’s statement revealed the hope of the trip. “A light has gone out,” it said, “but the hope he gave us will burn forever.”

On Wednesday night, Obama paid another uncommon tribute to Peres. He issued a proclamation ordering that the U.S. flag fly at half-staff throughout the country to honor a man who had become something of a mentor to the American president.

We cannot know with certainty, but if Shimon Peres had been a more successful politician, if terrorist groups had not sabotaged his career, a key part of the Middle East might look quite different today.

Peace between Israelis and Palestinians alone would not fix the Middle East. Syria, Iraq, Yemen – so many of the region’s trouble spots – might still be aflame anyway. But that one feverish dispute, the one between Israelis and Palestinians, might just have come to an end.

Peres’ dreams were not only about diplomacy and state-building. He had a child-like fascination with technology and innovation, and saw it as intricately connected to a better future for Israel and its neighbors. His exotic notion of a “Red-Dead Canal” – linking the Red Sea and the Dead Sea to create a zone of technology, trade and prosperity for Israelis, Jordanians, and Palestinians – seemed like a science-fiction fantasy. (Although it may just happen as part of an even grander idea, the Valley of Peace).

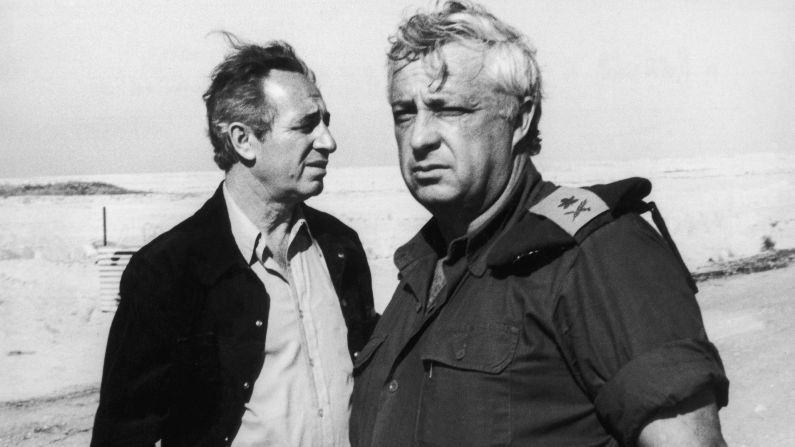

Peres arrived in the British-ruled territory of Palestine in 1934, when he was an 11-year-old boy named Shimon Persky, fleeing antisemitism in what was then Poland, and worked to build the dream of rebuilding the modern Jewish state. As the state came under attack from its neighbors, he worked to turn Israel into a military powerhouse, complete with a nuclear program, arguing that peace would only come when Israel’s enemies understood they could not destroy it.

Peres was never elected prime minister, although in 1996 he came close, when he was running after a Jewish terrorist opposed to the Oslo peace assassinated Rabin. The polls showed Peres far ahead of his challenger, Benjamin Netanyahu. But then the Palestinian Islamist group Hamas launched a series of bombings, blowing up city buses, restaurants, and shopping malls. The terrorists tilted the election to the security candidate, Netanyahu.

Yet despite his poor performance at the polls, he became a beloved national figure, serving as Israel’s ceremonial president until 2014. When his term ended, he made a hilarious video as a former president looking for a new job.

Today, with Israel’s right now in control of the government, Peres the optimist might have been able to detect a silver lining in something that came after his death. Israel’s Education Minister Naftali Bennett, a rightist, directed that all school children spend part of a school day learning about Peres.

Peres would likely take comfort in sharing his hopeful vision with young people. Indeed, just last year he said: “My greatest mistake is that my dreams were too small.” Yet with no end in sight to the current deadlock, it is no surprise that so many feel that the loss of Peres will leave the Middle East lost, too.