#MAGA. #MeToo. #Fake News. A trio of hashtags that have dominated 2017 – a polarizing year dominated by the arrival of Donald J. Trump in the Oval Office.

If 2016 marked the revenge of the forgotten – Trump’s victory, Brexit, and the rise of populist nationalism – that revenge has this year translated into boiling antagonisms: not so much shaking things up as blowing them up.

It has been a year of protest, and not just from below. The President of the United States has protested more loudly and often than most on a range of subjects, from “Crooked Hillary” to kneeling NFL players and, of course, “the fake news Russian collusion story.”

It all began with the White House’s inflated estimates of the size of the crowd at his inauguration, after which Trump described journalists as “among the most dishonest human beings on earth.”

The very next day, in Washington and around the world, millions of women protested against Trump and for their rights. These two events were a sign of things to come.

Women's marches around the world

The mood of insurrection was everywhere.

In Britain, one year on from the bitterly divisive Brexit referendum, the public protested about being railroaded into an unnecessary general election by depriving Prime Minister Theresa May of the increased majority she craved and robbing her of the slim one she had inherited from her predecessor, David Cameron.

Oxford Dictionaries declared the word of the year to be “youthquake” (which I didn’t even know was a word), in part because of the way young voters turned out for UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

As Casper Grathwohl of Oxford Dictionaries put it: “(A)t a time when our language is reflecting our deepening unrest and exhausted nerves, it is a rare political word that sounds a hopeful note.” (Antifa was also in the running.)

The people of France protested by turning their backs on the political establishment and electing a neophyte as President.

The people of Germany elected a far-right party to the Bundestag for the first time in almost 60 years in protest of Angela Merkel’s generosity on immigration. And next door in Austria, the electorate opted for a coalition that gave the far-right Freedom Party key posts in government.

Even in Russia, thousands of people protested, angered by corruption and frustrated by the everlasting rule of Vladimir Putin – who ended 2017 by saying he’ll run again in 2018.

Throughout much of the world, the rift between citizens and elites seemed to get deeper. Maybe that’s because of the stunning increase in inequality.

Since 1980, the richest 0.1 percent of the world’s population has increased its collective wealth by as much as the poorest 50 percent. While global poverty has been dramatically reduced in that period, many of the developed world’s middle classes are no better off.

Inequality has risen rapidly in North America, China, India, and Russia.

#MeToo

In 2017, protest went viral, too. The #MeToo hashtag revealed an iceberg of sexual harassment in the US that had been hidden for decades. After disclosures about Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein – allegations he denied – #MeToo was tweeted over half a million times in the space of a day.

As Sophie Gilbert wrote in The Atlantic: “…uncovering the colossal scale of the problem is revolutionary in its own right.”

Astonishingly, #MeToo survived the ever-shrinking news cycle and was transformed into what seems to be a real cultural shift. Time magazine named as its Person of the Year the “Silence Breakers.”

As evidence spread of sexual abuse and worse among politicians, businessmen and media personalities, the powerful were brought crashing down. It was perhaps the most heartening example yet of mobilization through social media.

Read: #MeToo’s global moment: the anatomy of a viral campaign

Although the #MeToo hashtag went viral online, it was sparked by solid, patient research in the old media – hat-tip to the New York Times and the New Yorker for their work on the Weinstein story.

There has been some outstanding journalism this year by institutions that were written off years ago as “old media,” even as their reporting has often been denigrated as #FakeNews.

President Trump had used the term in more than 170 tweets since taking office. Collins Dictionary made the phrase its word of the year.

It also became perhaps the most emotive term of the year. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron addressed Trump directly: “Fake news is not broadcasters criticizing you, it’s Russian bots and trolls targeting your democracy.”

But it has become the cheap currency of denial for everyone from Syrian leader Bashar al Assad to Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi to the Russian Foreign Ministry.

The G-zero world

President Trump has given a whole new meaning to “American Exceptionalism,” the term used by presidents in modern times to proclaim America’s indispensable leadership role.

The Trumpian version of this sees the US as the victim of its own generosity. In this world, the Germans and the Chinese, for example, are eating America’s lunch. It is “an arena of continuous competition,” as Trump’s national-security statement put it.

Russia and China “seek to challenge American influence, values and wealth,” Trump has said.

In effect, this administration is acknowledging the coming of a G[ravity]-zero world – one where international leadership is lacking, where global governance is weakened.

The decline of “Pax Americana,” the rise of China and India and Russia’s readiness to project its military clout suggest we’re getting there.

Trump’s path to “Make America Great Again” (#MAGA) is a narrower nationalistic one, which has meant withdrawing from the trans-Pacific free-trade agreement and the Paris climate accord, to give but two examples.

Trump prefers bilateral deals and has said so frequently. Above all, when he came to office, he wanted “a strong and enduring relationship with Russia and the people of Russia.”

That hasn’t happened – despite the President’s oft-expressed admiration for Vladimir Putin – because the administration has spent much of its first year trying to get past the quicksands of investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 US election – and anyone who might have colluded with it.

The Kremlin’s optimism that deals could be done with the Trump administration – on sanctions, Crimea and Syria – quickly frayed into frustration and then exasperation. Last week, President Putin wrote off 2017 as a year of “delirium and madness” in US-Russian relations.

The language has become more adversarial with every passing month. On North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile program, for example, President Trump said: “China’s helping, Russia’s not helping; we’d like to have Russia’s help.”

Moscow’s response is that US saber-rattling – through military exercises with the South Koreans and the White House’s threatening rhetoric toward Kim Jong Un – is making things worse.

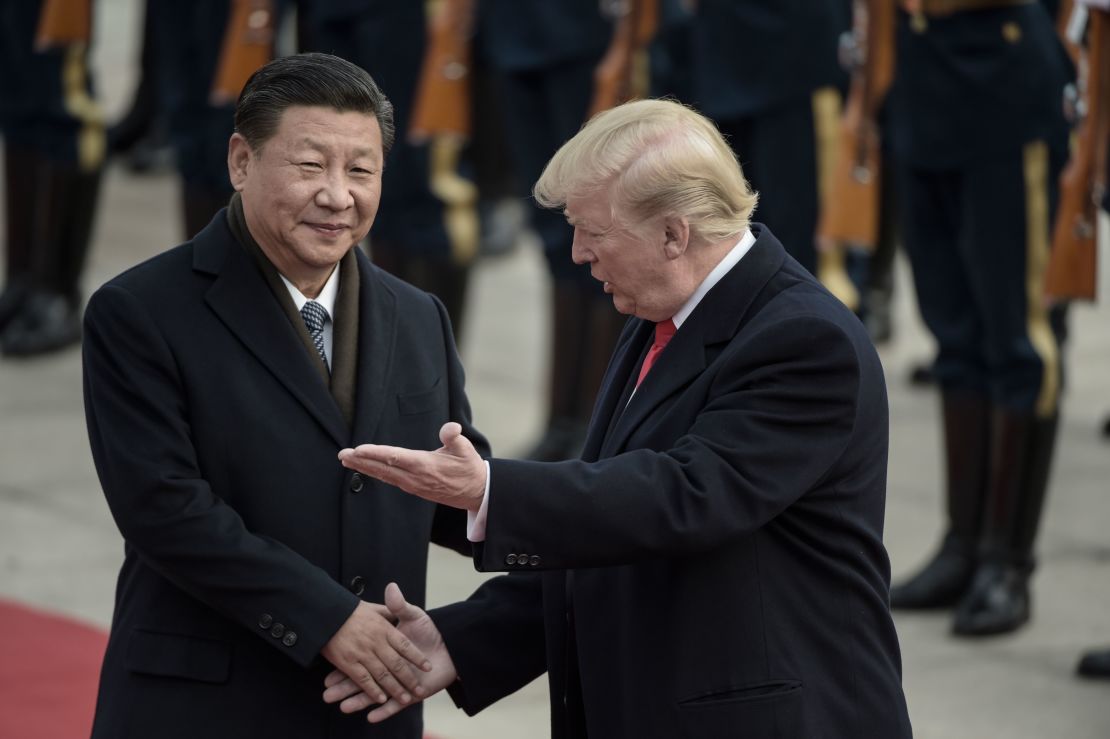

To Trump, personal chemistry with other leaders has been very important. In the minus column, Angela Merkel; in the plus column, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Trump said during his state visit to Beijing that he wanted to collaborate as equals: “working together to solve not only our problems, but world problems.” But weeks later, the administration’s national-security strategy labeled China as a competitor and warned that “the United States will no longer turn a blind eye to violations, cheating or economic aggression.”

While US foreign policy this year might be seen as a work in progress, Xi has shown remorseless focus.

He declared China a “great power” no fewer than 26 times in his speech to the Communist Party congress, according to the New York Times.

The evidence for this is everywhere, from the $900 billion “One Belt One Road” initiative to build infrastructure across Asia, to a new military base in Africa and new “Chinese-owned” islets in the South China Sea.

Russia, too, has carved out greater influence – driving the postwar process in Syria in concert with Iran and Turkey, with the US relegated to a playing only a bit part.

President Putin has also courted the Saudis and Egypt. The first-ever visit to Moscow by a Saudi monarch took place in 2017, and with it a raft of deals. The Russians and Saudis have become critical players in supporting oil prices by agreeing to production cuts.

If there’s any part of the world that’s evidence of “G-zero” it’s the Middle East. For sure, the caliphate of horror is over. In 2017, ISIS was expelled from Mosul and Raqqa and driven underground. It is not gone, but is returning to its insurgent roots.

In its place, a much more dangerous confrontation has begun to take shape. The vacuum left by ISIS in Iraq and Syria has often been filled by pro-Iranian Shia militia. Iran’s dream of a land bridge connecting Tehran with Beirut came a step closer in 2017.

That (and other alleged expansionism by Iran, in Yemen, for example) has in turn prompted a much harder line toward Tehran by Saudi Arabia, whose young Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman likened Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to Adolf Hitler.

After accumulating power at home with a dramatic tide of arrests for corruption, MBS (as he’s known) has accused Iran of “acts of war,” ratcheted up the pressure on Qatar (seen as too friendly with Iran) and was accused of spiriting Lebanon’s Prime Minister from Beirut in a forlorn effort to turn the Lebanese against Hezbollah.

The looming crisis between these two regional powers could make ISIS seem like a minor irritant.

GIFs and slime

If you got this far, my thanks. I am well aware that your mobile phone will soon seek to distract you. After all, the number of active phone connections (7.7 billion) for the first time exceeds the world’s population.

Compare this to 2001, when more than half of the world’s population had yet to make their first phone call.

According to Facebook, more than 500 billion emojis were shared this year on its Messenger service. And according to GIPHY, a library of digital animations, more than 2 billion GIFS were shared every day.

Plenty of them were about slime, which is hardly surprising, as the most popular “how to” query on Google this year was: “How to make slime.” (Not clear how many of those inquiries came from Washington, DC.)

But the most popular GIF of 2017, perhaps appropriately, appears to have been of a man blinking in confusion, as if to ask: “What on earth was that?”