Rogelio Galdamez has a worried look on his face, unsure if the home he’s building will be finished in time.

For the past five years, he’s been gradually putting as much money as he can toward building a home where he grew up near the border between El Salvador and Honduras.

But Galdamez is now suddenly in a much bigger rush.

Last week, the Trump administration announced the end of a policy granting Temporary Protected Status to more than 250,000 Salvadorans who fled the country’s civil war and natural disasters.

Salvadoran immigrants once protected by TPS will have 18 months before they will lose their legal status and could be forced to return home.

One of those people facing deportation is Galdamez , who says he has lived legally in the United States under TPS since 2001. He went back to El Salvador to see family on vacation recently – and picked up the pace on construction.

“I am not waiting around because there are many others,” Galdamez said as he worked on his home on the top of a remote hillside. “There are many that don’t have anything and are not prepared. I don’t want to be in the situation where I am not ready.”

Journey to America: ‘I ate rotten food but I made it’

Galdamez , 47, left El Salvador for the US in 1999 when his country was still recovering from years of devastating civil war.

As a boy, he said, he watched military planes bomb nearby hillsides as they hunted for communist guerrillas.

Guerrillas seeking shelter would come and kick his family out of their house. If you refused to leave they would shoot you, he said. Galdamez decided to head north.

“I slept on mountains, I drank dirty water, I ate rotten food but I made it,” he said of his trip overland through Central America and Mexico to make it to the US.

Then, in January 2001, a 7.7 magnitude earthquake devastated El Salvador. More than 1,100 people were killed, an additional 1.3 million were displaced.

Salvadorans who were in the US before the earthquake in their native country qualified for TPS because the thinking at the time was that they couldn’t return to an earthquake-ravaged nation. Today, TPS protectees are allowed to travel outside the US but Galdamez says he must pay a $665 fee to the US government for each trip.

Once in the US, Galdamez recalled, he worked on docks and vineyards. He is currently a driver for a landscaping company about 90 miles east of New York City in Riverhead, New York.

Of his 10 siblings, nine eventually joined him in the US.

With legal status, Galdamez bought a home, paid taxes and raised his three children, who were all born in the US.

‘Who will protect them?’

A rising tide of anti-immigrant sentiment and President Trump’s election victory made Galdamez worry that his immigration status could be revoked.

“Trump can’t give a speech without talking about immigrants and treating us the way he treats us, saying we are criminals,” Galdamez said. “We aren’t criminals, we are workers.”

But faced with the possibility of living illegally in the US and being separated from his family, Galdamez is considering a return to El Salvador.

That would mean bringing his three children – Marelin, 15; Selhvin, 10; Josslin, 6 – to a country where they have never lived. Galdamez is separated from the children’s mother.

“They know nothing about El Salvador,” Galdamez said. “But if [immigration officials] get me and send me back and my children will stay there, who will protect them?”

Marelin, Selhvin and Josslin would face a very different life than the one they know in the United States. They worry they might not ever be able to fit in.

Galdamez ‘s three children talk amongst themselves in English rather than Spanish and say they are not used to the slow Internet and roosters that wake them every morning at 5am.

“For us it’s going to be really hard,” says Marelin, a teenager who easily switches from English with her siblings to Spanish with her father. “People look at you differently because you are from the United States. I keep telling him, ‘I like it here, but I wouldn’t live here.’”

They may not have much of a choice.

Other Salvadorans are also getting ready if they need to return home, Galdamez said. He has noticed it is harder to find workers to help the construction on his home.

One of the world’s most dangerous countries

For decades, El Salvador has been wracked by gang violence, making it one of the most dangerous countries in the world, according to the United Nations.

Even in the remote countryside where Galdamez is building his home, the gangs block roads to impose taxes and terrorize the population.

In just the first two weeks of 2018, at least 115 people have been murdered, police told CNN. In 2016, there were 5,278 homicides in El Salvador, according to the most recent full-year statistics from the US State Department, which on Wednesday issued a Level 3 warning advising US citizens to reconsider travel to the country.

Exodus of Salvadorans: A huge economic blow

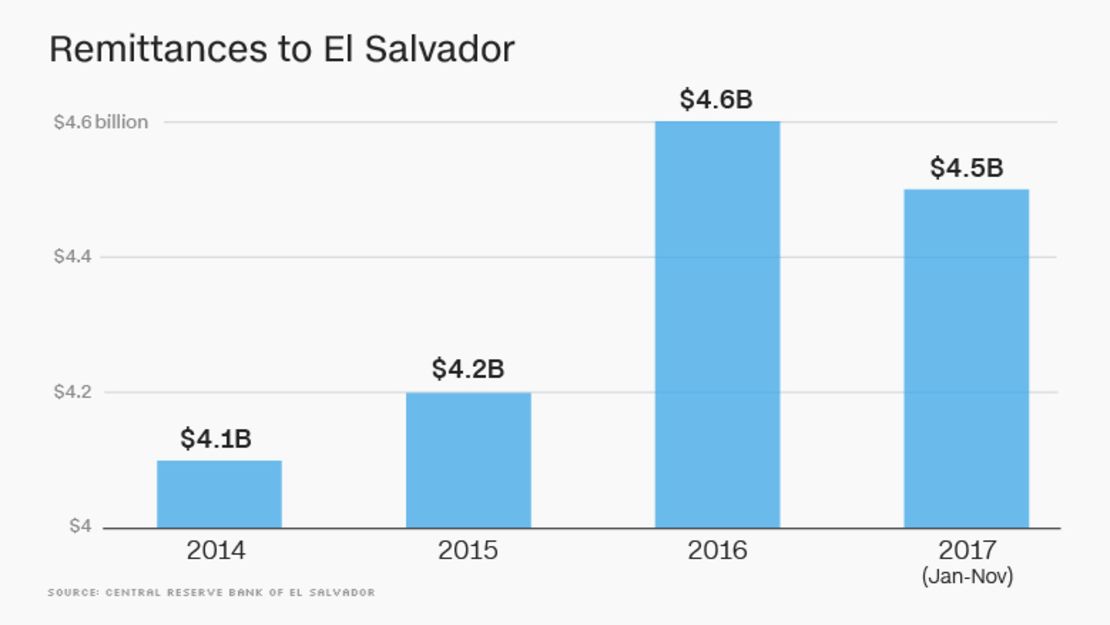

The end of TPS could also reduce some of the billions of dollars, known as remittances, that immigrants send home, a crucial influx of cash for the country.

Salvadorans sent home $4.5 billion to loved ones in the form of checks, wire transfers and greenbacks from January to November last year, according to the country’s central bank.

Remittances equal nearly one-fifth of El Salvador’s entire economy. The 2017 figure is on pace to become the all-time high for remittances, according to central bank numbers.

The amount of money sent home to loved ones also dwarfs the $88 million that El Salvador received in aid from the United States last year.

Experts say Salvadorans in the United States could decide to send as much money home as possible before the protections end in 2019. They also caution that American employers may fire Salvadoran employees who will lose their ability to keep a job.

Related: Trump clamps down on El Salvador’s ‘lifeline’

“The worry is that if there were a massive deportation,” Galdamez said, “This would become, I guess I would call it a hell. It’s a disaster. Everyone wants to work but there isn’t any.”

Still, Galdamez said his only priority now is to keep his family together.

“The day I am not with them and they are not with me,” he said, “I think they are going to suffer and I will, too.”

CNN’s Natalie Gallón, CNN Money’s Patrick Gillespie and journalist Melissa Vida contributed to this report.