The public consensus among Republicans in Washington is clear: President Donald Trump is not going to fire special counsel Robert Mueller. But if he does, well, watch out!

For what, precisely, is another question. Over the past few days, with Russia probe chaos noises turned up to 11, the congressional GOP has offered – and, in House Speaker Paul Ryan’s case, “received” – assurances that Mueller’s job is safe. Ryan wouldn’t reveal his source, but it’s probably fair to rule out Trump’s Twitter feed, which hasn’t exactly been a font of affirmation.

The possibility that Trump would move to sack Mueller, something the White House insists isn’t on the table, has been a point of anxiety since the former FBI chief’s appointment last May. Part of that is on Trump, naturally, and his itchy Twitter finger. The country has for almost a year been an inflammatory “Fox and Friends” segment, followed by a tap-tap-tap-tweet away from a constitutional crisis. Now, as tensions ramp up and we begin to look around that corner, there’s little to suggest congressional Republicans would, under any condition, stand up in opposition to Trump.

Not that they aren’t talking. “If he tried to (fire Mueller), that would be the beginning of the end of his presidency,” said the ever-quotable senior senator from South Carolina, Lindsey Graham, on CNN’s “State of the Union.” He was repeating his own past remarks, just about to the word, but he never addressed the prospect of Republicans in Congress moving a measure – like, for example, the one he co-authored – to protect Mueller.

That kind of bipartisan bill, of which there are two now languishing in the Senate, would ensure the probe ran its natural course, not so much in defiance but in legally enshrined ignorance of Trump’s whims. Anyway, it ain’t happening. At least not this year. On Monday, Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn, noting that any bill of that nature would eventually end up on Trump’s desk, explained why.

“I don’t see the necessity of picking that fight right now,” the Texas Republican told reporters. On its face, the point is simple enough, especially as Congress runs up against another deadline to fund the government. But it says a lot more: This has been the GOP attitude with regard to Trump since the 2016 primaries. He called Mexicans “rapists.” He targeted a federal judge over his family’s Mexican roots. He was accused by multiple women of sexual harassment and caught on tape bragging about sexual assault. He divided the blame between neo-Nazis and people protesting the neo-Nazis after the deadly violence in Charlottesville. In each case, and so many more, Republicans have spoken out, then duly quieted down and voted to advance their mostly shared legislative agenda.

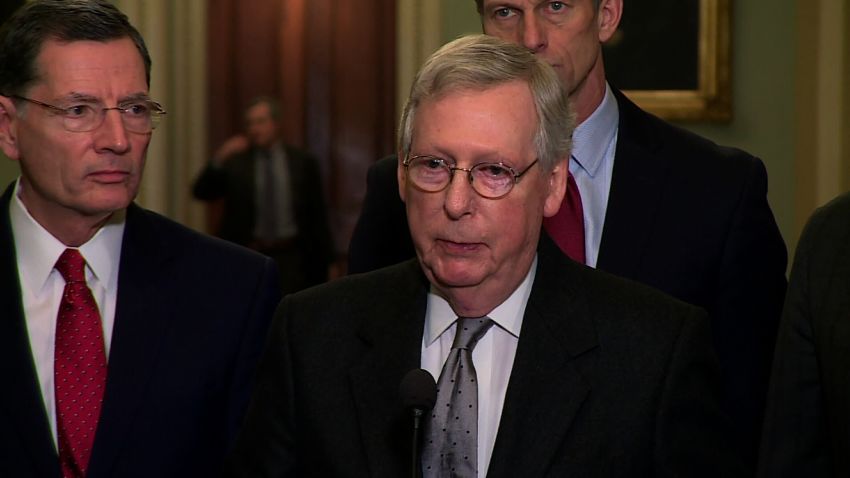

It hardly takes a genius pundit to see that elected Republicans, at least those with a desire to maintain their station, are either in accord or terrified (or both) of Trump and their – well, his – political base. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s silence in the immediate wake of Trump’s latest onslaught undermined the tough talk from select members of his caucus. He spoke up on Tuesday, defending Mueller’s integrity and expressing confidence in his fate, but, like other Republicans, waved off questions over legislation to shield the probe.

For all the rationalizing, the politics behind the GOP’s lockstep here is pretty simple. They want peace with the White House because, in a fight, polls show Trump would come out on top.

An NBC/WSJ survey released Sunday asked Republican and “lean Republican” Trump voters if their loyalties lie more with the party or the President. The split was staggering (if not surprising) – 59% said they considered themselves Trump supporters first. Only 36% told pollsters the GOP was their priority. Other polling consistently shows that, despite Trump’s underwater overall approval ratings, he remains in good standing with Republican respondents.

But again, this isn’t just a parlor game. Trump and his allies have repeatedly tested Capitol Hill Republicans. The President last weekend assailed Mueller, by name, and one of his lawyers, John Dowd, publicly asked – no, prayed – for the investigation to be halted by the Justice Department. Then there was the dismissal of former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, by Attorney General Jeff Sessions, late Friday and news Monday that Trump will hire Joseph diGenova, a Washington attorney who has alleged that the FBI and the Justice Department are framing up the President.

If you think of those developments as warning shots, a test to see how Congress might respond to further escalations, then the White House learned a lot this week. Rather than view any of the above as a sign of what’s to come, and prepare to act like it, Republicans either tamped down concerns, ignored them or offered splashy quotes with little substance behind them.

“I do not think that the President is going to order anyone to fire Mr. Mueller. That would be a terribly serious mistake,” said Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, offering a representative take. “And it’s important to remember that the President cannot directly fire Mr. Mueller. Only the deputy attorney general can do that under the department’s regulations.”

Collins is right on the process, but given all we’ve seen in the past year, and especially over the last few days, the suggestion that those obstacles are sufficient, or inviolable to Trump, is – even in these quite serious times – laughable.