Editor’s Note: Tim Naftali, a CNN presidential historian and clinical associate professor of history and public service at New York University, is writing a new biography of President John F. Kennedy. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Tim Naftali: For years CIA shielded from public view all its daily briefings for the president

It released this week 28,000 pages prepared for Nixon and Gerald Ford, Naftali says

In the last few weeks the two presidential nominees have received their initial intelligence briefings. Although the experience must have been different for each – it was Donald Trump’s first, whereas Hillary Clinton is an experienced intelligence consumer – they were both recipients of a product authorized by President Barack Obama, the intelligence community’s most important customer and the official who more than anyone else controls how intelligence is shared inside and outside the US government.

For years the CIA shielded from public view every single one of the briefings that it produces daily for the president’s eyes only, arguing that even letting go one 50-year old briefing could harm national security.

Only in recent years did the CIA revise its traditional stance, releasing in September all of the daily, classified newsletters it had produced for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. And on Wednesday, the releases continued, with the posting on the Web of the 28,000 pages prepared for Richard Nixon and his successor, Gerald Ford.

While a considerable amount remains edited out for national security reasons there are some historical gems, which not only hint at how well our intelligence community did in the Cold War but give us decades later a sense of the awesome responsibilities that come with being president.

Whoever occupies the White House in January will receive a similar product, tailored to his or her interests and designed not only to keep the White House informed but to lower the probability that the president will be surprised. And in this era of international terrorism, the cost of surprise is potentially as high as it was in the worst moments of the Cold War.

The President’s Daily Brief, as these daily classified newspapers came to be called – Obama apparently reads his on an iPad – emerged out of Kennedy’s anger at how the CIA had bamboozled him into authorizing an attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro that came to be known as the Bay of Pigs fiasco.

Since June 1961, the CIA has prepared for 10 presidents a special digest of information on subjects it believes the chief executive wants and needs to know about. It includes data collected across all intelligence platforms – from spies to spy satellites to Alan Turingesque code breaking. As far as the intelligence community is concerned it is its Tesla or Breitling.

Kennedy may not have read every one of his reports, but when he did, he often reacted energetically, sending questions back to the CIA for clarification. Indeed one of the last things he did before leaving for Texas in November 1963 was to send a request for more information on something he had read in his daily intelligence briefing.

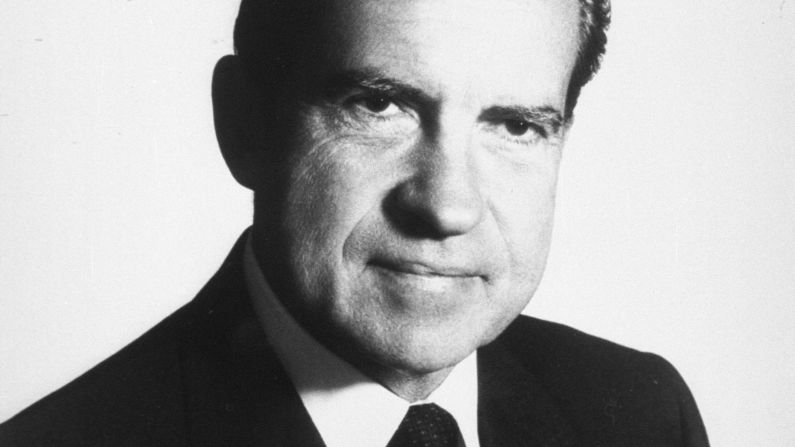

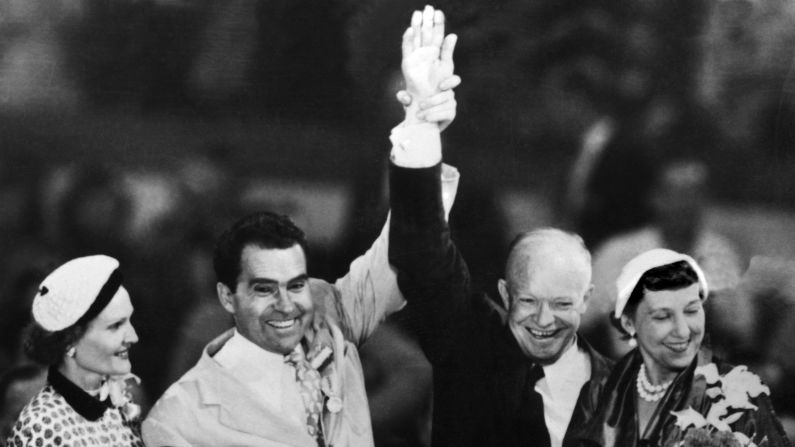

The two presidencies covered in Wednesday’s release involved leaders who had diametrically opposed views on this source of highly sensitive knowledge. Nixon, it seems, hardly read his. Nixon who did not like to be around people outside his inner circle, insisted that the briefings go to him indirectly, through Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser.

As a result, the agency was never quite sure what he thought of the product. Whatever presidential feedback there was came from Kissinger to the CIA, not from Nixon himself. (Although I was director of the Nixon Presidential Library when we processed Nixon’s personal copies of the briefings for eventual review and release, I did not look at any of them. The personal copies might have his marginalia, telling us more about how he absorbed or didn’t absorb this material. The CIA released only its copies of the reports prepared for Nixon.)

Ford, on the other hand, had far less self-confidence in foreign affairs and relished these documents as a source of tutoring not only about what mattered in the world but how those issues and areas were developing. Until late 1975, a CIA officer stood by him practically every day as he read the President’s Daily Brief, ready to answer any question Ford might have.

The complex and conspiratorial Nixon brought a prejudice against intelligence, especially the CIA, to the job. He was convinced the Ivy League leadership of the CIA had not only voted for Kennedy but had sabotaged him in the 1960 election. There is evidence that Nixon tended to let the briefings pile up, unread.

But Nixon’s issue with the President’s Daily Brief was not just social insecurity. In his chatty and absorbing memoir, Nixon’s first CIA director, Richard Helms, wrote that his boss “showed little interest in an independent intelligence service” and was “perpetually cranky in his relations with CIA.” Now that we can read most of these briefings, we see a major source of the crankiness. It must have annoyed Nixon that in a number of high-profile areas, the agency was routinely telling him things he certainly did not want to hear.

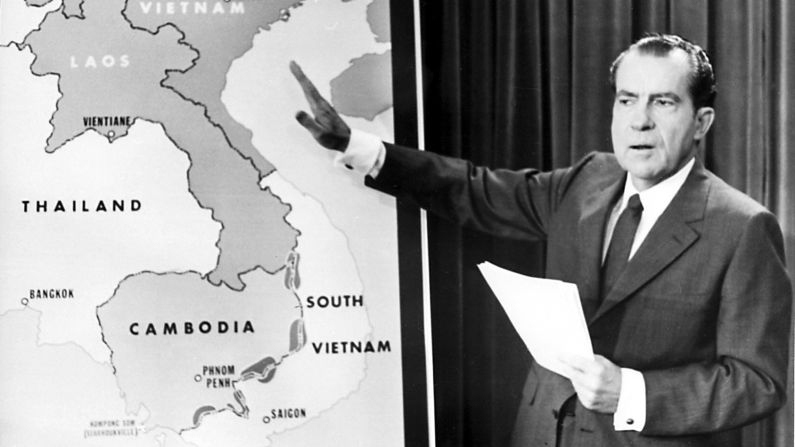

The bad news on the Vietnam War

Practically every morning, the President’s Daily Brief reminded Nixon that North Vietnam and its communist allies in Southeast Asia were winning and that US military strategy was failing.

US intelligence had broken enough North Vietnamese ciphers to be able to follow the infiltration along the Ho Chi Minh trail (via Laos and Cambodia) of North Vietnamese regular troops into South Vietnam. The number of troops was staggering and belied the Pentagon’s estimate that US bombing raids had a net effect of reducing the number of North Vietnamese soldiers fighting in the south.

After Nixon decided in April 1970 to send US troops 20 miles into Cambodia to clean out North Vietnamese bases along the border, the CIA reported that these operations were failures. The North Vietnamese just abandoned the bases and retreated farther into Cambodia, rather than pick a fight with the better-equipped US army. “Communications intelligence,” the CIA writers noted on June 4, “provides nearly a complete picture of these movements (11 regiments). … Most, but not all, of these relocations appear to have been in direct response to allied operations, reflecting the enemy’s anxiety to avoid contact while dropping back to more secure areas.”

Warning about Chile and Allende

Throughout 1970, the CIA warned Nixon and Kissinger that the Chile’s Salvador Allende might be the first Marxist to gain power through the ballot box.

On January 24, 1970, the President’s Daily Brief noted that “if the leftist parties can submerge their difficulties, (Allende) might be in a strong position to win the presidency.”

Six months later, on July 18, the agency added that though the conservative candidate appeared to be slightly ahead, “there were no reliable polls on which to base predictions” and Allende was running a strong campaign. It was a three-man race, and if no one won a majority of the vote, the selection of the president would go to the Chilean Congress. Allende was expected to strike a deal with the other leftist candidate if that happened.

One day before the election, September 3, the CIA predicted that no one would win a majority and that what the Congress would decide was “anybody’s guess.” Although Allende won with only 36.2% of the vote, the CIA told Nixon on September 7 that he was likely to become president.

Not only was it likely that the Congress would select him, the CIA cautioned that “there is no indication at this time that military leaders are planning to move to prevent Allende from becoming President.” When the head of the Chilean air force approached the US Embassy a few weeks later, saying that the military would only oppose Allende if this could be done constitutionally, the CIA poured cold water on any hopes the White House might have of a coup, saying that this man had not been successful in rallying the Chilean armed forces before.

Kissinger would later write that the White House’s reaction to Allende’s victory was “stunned surprise” and that Nixon was “beside himself.” We now know that had they been doing their daily reading, it should not have been a surprise at all.

Yom Kippur War and superpower confrontation

Wednesday’s release was not just about misconceptions and missed opportunities. There were also revelations from the 1973 Yom Kippur War showing how the White House can act on intelligence in a crisis. There was a moment, at the tail end of that war, when the two superpowers seemed to come close to a clash, possibly one involving nuclear weapons.

For some time we have known that in late October 1973 the United States feared the Soviets might be preparing to intervene to help the beleaguered Egyptian Third Army, which was surrounded by the Israelis near the city of Suez.

The Nixon administration, on the recommendation of Kissinger, decided to lift the worldwide US military alert late in the night of October 24-October 25 to DefCon III, its highest worldwide level since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

With Nixon mired in Watergate – this was the period of the Saturday Night Massacre when he decided to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox and the leadership of the Justice Department collapsed – Kissinger worried that the Soviets doubted US resolve and needed a reminder.

The declassified President’s Daily Briefs provide startling new evidence on what exactly US intelligence had discovered about Soviet activities and why the Nixon administration had reason to be concerned. In the second volume of his memoirs, Kissinger hinted that he made his alert recommendation because of “ominous reports in especially sensitive areas” but didn’t reveal more.

It turns out Kissinger and Nixon worried that the crisis might go nuclear. American intelligence had detected a Soviet ship headed for Egypt that it believed was carrying nuclear weapons. In addition, the United States detected two Soviet amphibious ships nearing Egypt. Ultimately, Soviet troops never landed in Egypt, and the Soviet flotilla 100 miles off the coast of Egypt dispersed within hours of the US alert. The full story of the ship thought to have nuclear weapons remains to be told. It arrived in Egypt on October 24. Its fate and that of its cargo may be in the still classified sections of what was released Wednesday.

The picture drawn by the CIA in Nixon’s briefings was not always accurate. The agency failed to predict the Egyptian and Syrian attack on Israel. On October 5, 1973, the day before attack, the White House was told, “Military exercises now going on in Egypt are larger and more realistic than previous ones, but the Israelis are not nervous.”

In Southeast Asia, the agency predicted that local communists, Khmer or Lao, would never be able to defeat America’s allies without the support of the North Vietnamese, who were an effective fighting force. This would prove to be a mistaken assumption once the United States withdrew militarily from the region.

And some potentially key gaps for us remain in the intelligence picture given to Nixon. There are many sections on the Middle East and some tantalizing items about Palestinian terrorism and presumably the Black September Organization – one called “Fedayeen-US” from just after the Munich massacre and another involving a foiled bomb plot in New York in March 1973 – that are still largely classified.

There are also sections on North Vietnam and quite a few on South Vietnam that remain closed, especially from the tragic period in the fall of 1972 when Saigon intervened politically to prevent Washington and Hanoi from ending the war. There are also some sections where even the name of the country involved is still not declassified.

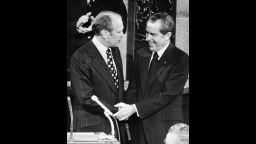

Ford’s different approach to CIA

When Ford became President in August 1974, the White House’s relationship with CIA improved dramatically. He choose to have these briefings in person, and their tone reflects the fact that US intelligence believed the President was listening.

Get our free weekly newsletter

When Ford headed to Indonesia in December 1975, the CIA warned him that Indonesian President Suharto would ask him about the US position on Indonesia’s plans to invade the former Portuguese colony of East Timor: “Suharto will undoubtedly raise the question of Timor during talks with you in an effort to determine US reaction to overt intervention.”

The agency made clear that though determined to use military force to incorporate the colony into Indonesia, Suharto was sensitive to US criticism and was even preparing to act without using US-supplied weapons to avoid later trouble with the US Congress. Jakarta needed continued American military assistance. The agency never felt close enough to Nixon, and was so often kept in the dark about his foreign policy initiatives, that it had rarely provided similar guidance in a President’s Daily Brief before his trips abroad.

In this case, Ford made up his mind not to stand in the way of Indonesia’s invasion – an event that would lead to a brutal 25-year occupation causing an estimated 200,000 deaths – a decision he would later tell historian Douglas Brinkley he understandably regretted.

“I mean I truly,” Brinkley quotes him as saying in his fine biography of Ford, “honestly feel for those families which suffered losses. I’m sorry for them. The whole thing was tragic but I only learned the extent to what happened there after I left Washington. Then it was too late.” Not only did Ford read his briefings, he also could admit his big mistakes.

The world of the President’s Daily Brief only got more complicated for a president after 9/11. Not only must you read about what adversarial countries with armies are planning and doing, you have to keep track of dozens of byzantine plots involving shadowy figures with often similar names. And you have to do that six days a week, for four or, if you are lucky, eight years. No wonder presidents seem to age fast.