Story highlights

Sadiq Khan plans vehicle free areas of central London

Almost 10,000 people killed by air pollution each year in the city

Cities across the world now going vehicle free

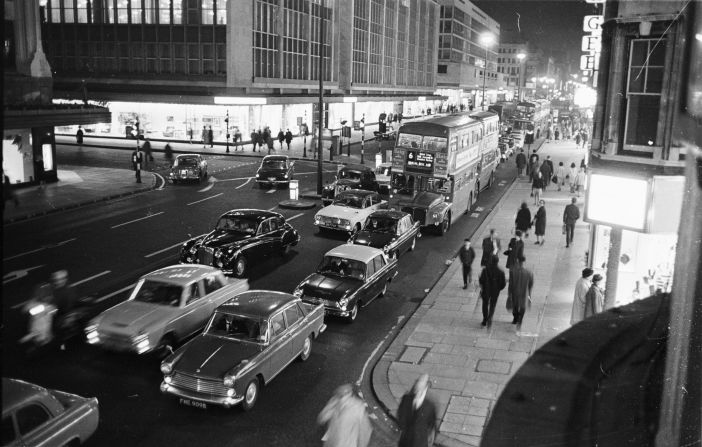

During peak hours, Oxford Street barely moves. The road becomes a red wall of steel as buses grind to a halt, and the pavement overflows with squashed shoppers and tourists.

But new Mayor of London Sadiq Khan has a plan to transform the capital’s busiest street into an urban oasis. From 2020, vehicles will be banished from the 1.2-mile highway.

“The vision is for there to be a street lined with trees and pedestrian squares, and change the whole experience,” Khan told CNN.

Around four million people visit Oxford Street each week, London’s retail heartland, which generates over £5 billion ($6.6bn) a year.

But in addition to being London’s busiest street, it is among the dirtiest. Oxford Street has served as a thoroughfare for buses and taxis since the 19th century, with up to 300 double-deckers crawling along it during rush hour, often using high-polluting diesel engines.

In 2014, a leading air quality expert found the world’s highest concentrations of Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) on Oxford Street, a pollutant generated by diesel fumes that causes lung disease and respiratory problems.

Such conditions are illegal, Khan notes, with the British government currently facing a lawsuit over breaching EU air quality limits.

“If you look at legal requirements on levels of Nitrogen Dioxide in particular, Oxford Street gets in the first week of January what it should in an entire year,” he says. “That’s one of the reason why there’s an urgency to air quality plans.”

Londoners pay a high price for the filthy air, which kills almost 10,000 citizens a year. In the worst hotspots, children grow up with stunted lungs, and cases of asthma and heart disease increase.

The plan

Khan is himself a victim of London’s modern plague, having been diagnosed with adult-onset asthma. He was elected in June on the promise of a “greener, cleaner” London, and the vehicle ban on Oxford Street is a cornerstone of this vision.

The idea has been considered since the 1970s, when heavy restrictions were introduced on private cars, but further advances have been thwarted, often by local businesses concerned about deterring consumers.

Circumstances now appear more favorable, with the powerful New West End Company retail group offering guarded support for a “vehicle free” zone, and Khan believes he can please all stakeholders.

“We are working closely with the retailers, the council, the residents, and we want to phase the project in a number of stages to reduce disruption,” he says.

The plan is to initially cut 40% of buses on Oxford Street, ahead of opening a new tube network - the Elizabeth Line - in 2018, which will include stations at either end of the street. City Hall will then embark on an overhaul of bus routes across London to divert the remaining buses.

The ban will be implemented in two parts, initially covering half of the street from Tottenham Court Road to Oxford Circus, and then up to Marble Arch. New taxi ranks will be installed on side streets to support disabled access.

The traffic jams would then be replaced with a tree-lined boulevard, offering a blank slate for new possibilities from new pop-up stores and markets to “oasis spaces” for weary shoppers.

Instant impact

If the vehicle ban can be implemented, there is reason to believe it can have a swift and powerful health impact.

The Champs Elysee in Paris saw a 30% reduction in NO2 after a one-day partial car ban in the city.

“If the traffic is stopped the pollution falls immediately,” says Frank Kelly, professor of environmental health at King’s College London. “In years to come the health benefits will be considerable.”

Clearing the street should also bring economic rewards. The new tube stations are expected to bring in millions more visitors than existing transport services, and generate a further £1 billion ($1.33bn) a year.

Complete package

The plans for Oxford Street are part of a wider package of air quality reforms.

Khan also hopes to apply a vehicle ban around Parliament Square in Westminster, building on the success of similar schemes in Trafalgar Square and South Kensington.

He has bought forward plans for an Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) to 2019, and will extend it beyond the city center. The ULEZ will impose new emission limits on vehicles in line with EU standards, and a charge for non-compliant vehicles.

The citywide overhaul of buses will see the fleet transitioned to low emission engines from 2018, including a new fleet of electric vehicles, with new taxis required to adopt zero emission systems.

The mayor also intends to spur innovation among business leaders, and will host a conference with bus manufacturers.

“I will say ‘if you can design buses that are electric, hydrogen, or hybrid cell…we are the biggest purchasers around,’” says Khan.

Activate citizens

The population of London will soon reach 10 million, and the mayor says it is necessary to “re-engineer” the city to prioritize active travel to protect the environment.

“If we don’t recognize that air quality is the biggest challenge of the 21st century we will keep designing a city that’s not fit for purpose,” he says.

“Planning for growth means a major shift in getting people out of their cars and on to cycling or public transport.”

He intends to encourage that shift by creating new, safe and attractive routes for cycling and walking.

His team are also installing air quality meters around the capital to give pollution readings, and advise walking, cycling or public transport accordingly.

Exhausting diesel

Khan’s proposals have been welcomed by activists as an improvement on the policies of former mayor Boris Johnson, but there are also concerns that a key issue is not being resolved.

“Oxford Street is very important – it is the highest level of pollution combined with huge exposure,” says Simon Birkett, founder and director of Clean Air London. “But the only solution to tackling London’s air pollution problems is to ban diesel…Diesel is responsible for 90-95% of NO2 exhaust emissions and there is no other way to (reach) the legal limit.”

The UK is currently three times over EU limits for NO2 and has committed to closing the gap by 2025, which Birkett argues cannot be achieved without a total diesel ban.

He points to opinion polls that show public support for such a step, and bans in other cities such as Berlin, as proof that the mayor must take action.

Khan is sympathetic but points out difficulties such as the personal circumstances of car owners, who would need to be compensated.

“Ten years ago many people bought diesel cars because they were told to as the concern then was carbon,” he says. “Now the concern has moved on to NO2 and I’ve said to the government ‘we need help on a national diesel scrappage scheme.’”

Global alliance

Khan admires the Mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo, who has implemented bold measures such as car-free days and a pedestrian zone along the River Seine.

He regularly consults with mayors of other major cities and sees opportunities for fruitful collaboration, from sharing ideas to bringing collective pressure to bear on vehicle manufacturers.

The mayor is happy to borrow from foreign counterparts – he hopes to install a cycle bridge inspired by Copenhagen - but also wishes to set the pace.

“I will pinch the best ideas from other cities but at some stage in near future I want us to be world leaders again,” he says.

Competition is heating up when it comes to car reduction. Oslo intends to ban cars from its city center, and Milan has similar plans. Madrid and Brussels are pedestrianizing swathes of their cities, and New York is experimenting with car free days.

New era

Urban car use may be in permanent decline, according to David Metz, professor of transport studies at University College London.

“The 20th century was the great age of the motor car,” says Metz. “But in the 21st century we see increased prosperity associated with decreasing car use in cities like London.”

According to Metz’s research, the proportion of journeys made by car in London declined from 50% in 1990 to 36% today. He expects that proportion to keep falling and for pedestrian-only spaces to spread.

With far-sighted leadership, the congested, dirty and dangerous streets of today could be the urban havens of tomorrow.