As the harsh North Dakota winter approaches and protests grow even more tense, the Standing Rock Sioux and their supporters are rising to crescendo in the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Now there’s a deadline: Authorities say they must leave the camps by December 5. Demonstrators say they aren’t budging.

Here’s a look at what they’re battling for and how it got to this point.

THE PIPELINE

The Dakota Access Pipeline is a $3.7 billion project that will transport 470,000 barrels of oil a day across four states. Specifically, it will pass through an oil-rich area in North Dakota where there’s an estimated 7.4 billion barrels of undiscovered oil. This oil would be shipped to markets and refineries in the Midwest, East Coast and Gulf Coast regions. This way, the project developer says, the United States could tap its own backyard for oil, rather than relying on imports from unstable regions of the world.

The pipeline would also be an economic boon, bringing an estimated $156 million in sales and income taxes to state and local governments as well as add 8,000 to 12,000 construction jobs, the developer says.

But this is the Dakota Access Pipeline on paper. When it comes to the real-world construction, things aren’t so clear-cut.

THE STANDING ROCK SIOUX

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe sued the US Army Corps of Engineers after the pipeline was granted final permits in July. The tribe says the project will not only threaten their environmental and economic well-being, but will also cut through land that is sacred. Construction of it, they say, will “destroy our burial sites, prayer sites and culturally significant artifacts.”

Faith Spotted Eagle, who lives on the Yankton Sioux Reservation of South Dakota, says it’s not up to researchers to determine what land is sacred.

“Archaeologists come in who are taught from a colonial structure, and they have the audacity to interpret how our people were buried,” she says. “How would they even know?”

She says 38 miles of the Dakota Access Pipeline cuts through territory that still belongs to Native Americans, based on a 1851 treaty signed at Fort Laramie in Wyoming.

THE PROTESTS

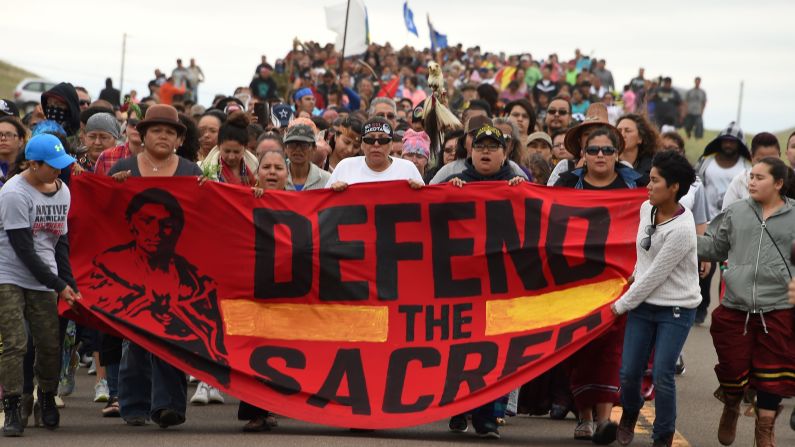

For months, hundreds of protesters from around the world have traveled to North Dakota to push back on the construction of this pipeline. The demonstrations have turned violent at times, as police dressed in riot gear tear gassed and pepper sprayed protesters during clashes.

Just before Thanksgiving, on an evening when temperatures dropped below freezing, police sprayed protesters with a water cannon.

THE CAMPS

A few makeshift camps in Cannon Ball, North Dakota, serve as temporary homes for many of the demonstrators. Tipis, tents and food trucks dot the snow-covered ground as flags from other tribes around the nation billow in the sky above.

Officials say they are shutting down the camps on December 5. They’ve also instituted a $1,000 fine for anyone taking supplies to protesters. But as that deadline looms, the people in the camps are digging in their heels, determined to stay.

Some residents of Cannon Ball, however, say the camps have been a nuisance. They also say you won’t see all Standing Rock Sioux there – many of the people residing in the shelters are from other parts of the country.

THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

It’s all about who you ask.

Dakota Access claims the pipeline would provide a safer, more environmentally friendly way of moving crude oil, compared to other modes of transportation, such as rail or trucks. Supporters cite the 2013 disaster in Quebec, where a train carrying crude oil destroyed downtown Lac-Megnatic when it derailed.

But one the Standing Rock Sioux’s arguments against it is that it doesn’t spur the country’s move away from crude oil. Americans should instead look for alternative and renewable sources of energy, Standing Rock Sioux Chairman David Archambault II said in September.

Opponents also worry about what the pipeline, which would go under the Missouri River, could do to the water supply if it ruptured.

North Dakota pipeline protests

Jessica Ravitz contributed to this report from Cannon Ball, North Dakota.