Story highlights

Extralegal shuanggui system facilitates abuse and torture, Human Rights Watch says

System is main method by which Communist Party investigates corruption

The gray, concrete building looms over the street in central Beijing.

Completely unmarked aside from a street number, its entrance is buttressed by barriers and fencing.

Inside lies an organization that strikes terror into the hearts of some of China’s most powerful people, and oversees a sprawling network of secret prisons where experts say torture and abuse are common.

The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) is the body tasked with investigating all 88 million members of the Chinese Communist Party for corruption.

China's corruption crackdown: The biggest victims so far

Witch hunt?

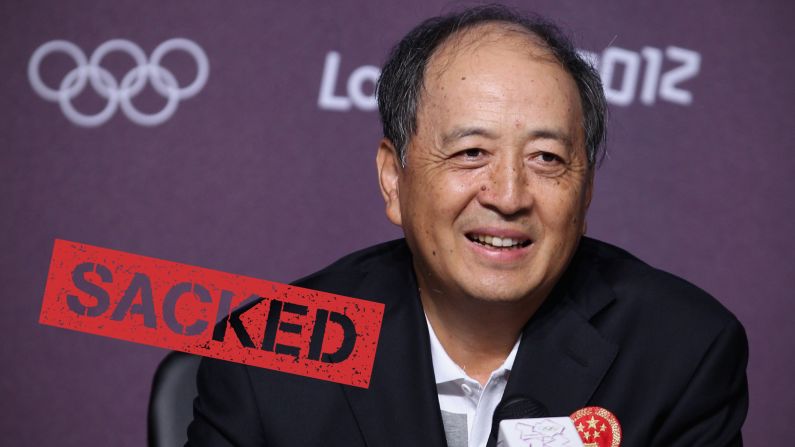

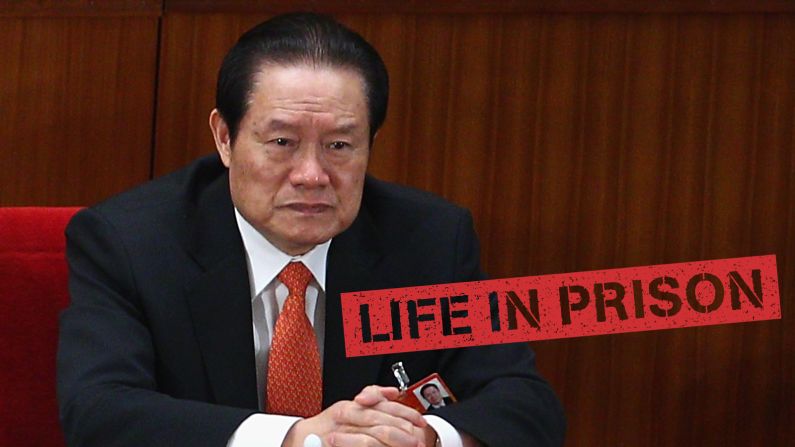

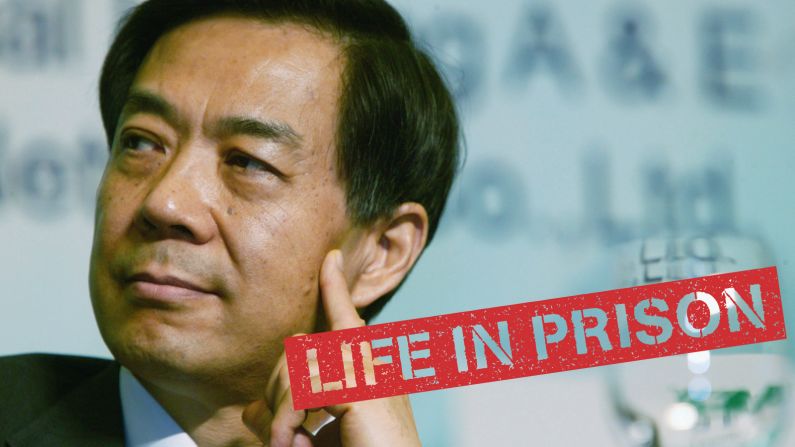

Cracking down on corruption has been a key goal of Chinese President Xi Jinping since he came to power in 2012, and his tenure has seen the downfall of several of China’s highest-ranking politicians, including former security tsar Zhou Yongkang and former top People’s Liberation Army general Guo Boxiong.

Xi has called for the Party’s investigators to tackle both “tigers and flies,” high-ranking officials and ordinary cadres.

Almost 300,000 people were charged with graft offenses last year, according to CCDI deputy secretary Wu Yuliang.

However, doubt has been raised over both the effectiveness of Xi’s push, and whether there are other motivations behind it.

“That’s the big question about the campaign: is it an anti-corruption effort or a political witch hunt?” said Andrew Wedeman, head of Georgia State University’s China Studies Initiative. “It’s part of both.”

The CCDI did not respond to a written request for comment.

Shuanggui

Party corruption fighters have powerful tools at their disposal, chief among which is the ability to summon any party member to an “appointed time and place,” or shuanggui, for investigation.

Shuanggui detainees are held in secret, for indefinite periods of time, during which they are brutally interrogated, sometimes fatally, according to a new Human Rights Watch report.

“Xi has built his anti-corruption campaign on an abusive and illegal detention system,” Sophie Richardson, HRW China director, said in a statement. “Torturing subjects to confess won’t bring an end to corruption, but will end any confidence in China’s judicial system.”

Wedeman said that the prospect of being hauled into shuanggui is “pretty terrifying” for ordinary Party members.

“There are tales of people basically falsely confessing just in hopes of getting out of the clutches of Party investigators and into the hands of regular law enforcement,” he said.

The system operates in secret, with many detainees held in hotel rooms and impromptu jails, usually with padded walls and never above the first story, in order to prevent suicides, said Jackie Sheehan, a China expert at University College Cork’s School of Asian Studies.

“If you hear there’s a separate system for Party members, it sounds like a perk, but it’s definitely not,” she said.

Torture

“The very nature of shuanggui itself is abusive,” said HRW researcher Maya Wang, pointing to the use of solitary confinement and cutting off detainees from their family and lawyers.

HRW estimates there were up to 66,000 shuanggui cases in 2015. The system operates outside China’s legal system, with detainees subsequently handed over to prosecutors, often with signed documents confessing their guilt in hand.

Investigations are conducted outside the regular legal system in order to “protect the Party’s reputation” and keep discussion behind closed doors, according to Wang.

“It’s a way to deal with their dirty laundry in private,” Sheehan said.

There are no laws or published rules governing the performance of shuanggui investigations, according to researchers Li Fenfei and Deng Jingting.

Detainees are kept in small cells and subjected to “various forms of physical and psychological abuse,” the HRW report said.

“I was not allowed to sleep; I had no food or drink, I was beaten … I was subjected to everything,” former official and shuanggui detainee Bao Ruizhi told HRW.

Lawyer Zhou Lifeng told researchers that “being subjected to cold and hunger is quite normal … there are also (other forms of) torture, like being strapped to chairs, beaten, insulted, deprived of sleep … there are varying degrees of torture in the cases I have handled.”

Does it work?

Shuanggui has been in use for around two decades, and while it is a terrifying prospect for many Party members, corruption has been endemic throughout that time, pointing to the system’s ultimate failure as a deterrent, Wedeman said.

“The assumption for these kind of systems is if you’re tough with crime you’ll get results,” said Wang. “The reality is that the use of torture and arbitrary detention often lead to quite contrary results.”

Detainees in shuanggui told HRW they would confess to almost anything to escape the system, making it effectively useless as an investigatory tool.

It also suffers from the same problem as many of Beijing’s attempted reforms, Wedeman said, “China is a huge, difficult to control state.”

While there are ongoing attempts to centralize the system, Party investigators are often loyal to local officials, making it unlikely they’ll go after their bosses and opening the possibility for politically motivated crackdowns.

“A lot of what Beijing wants, Beijing doesn’t get,” Wedeman said.

“They’re struggling with the very apparatus they created to fight corruption, which risks becoming an apparatus of corruption.”