Australian far right agitator Neil Erikson’s latest move might be his most cunning.

The self-proclaimed former neo-Nazi – found guilty this month of inciting serious contempt for Muslims in an offensive online video – is launching a new nationalist group called “Patriot Blue.”

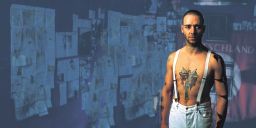

Patriot Blue is also the name of the fictional far right, anti-Muslim group in the upcoming Romper Stomper TV series, which reunites the director and several cast members from the iconic 1992 film by the same name, and is set to air over the Australian summer. In the movie, neo-Nazis targeted Asian immigrants.

The original film, starring Russell Crowe, created a storm of controversy in Australia and Britain for glorifying Nazi violence, and the sequel has already come under fire for giving a platform to extremists. Erikson hopes that appropriating the name will help him recruit the country’s next generation of far right followers.

“People who watch that show will look for something, so they’ll google ‘Patriot Blue’ and there we will be,” says Erikson, who has bought two “Patriot Blue” domain names and is already selling T-shirts online.

“The youth follow popular culture so if there’s a show that can symbolize some sort of counterculture, whether it’s skinheads or patriots, they’ll jump on board,” Erikson tells CNN.

Stan, the Netflix-style streaming service behind the new series, and the filmakers have declined CNN’s request for comment.

Even, if they legally prevented him from using the “Patriot Blue” name and the domains, Erikson’s hoping to generate enough controversy and attention from the stunt to help grow and keep his new movement alive.

‘How do I weasel my way into the conversation?’

The 32-year-old forklift driver pleaded guilty in 2014 to charges stemming from making threatening phone calls to a rabbi. He says he turned away from neo-Nazism after his fellow skinhead gang members beat up a 21-year-old Vietnamese student in Moonee Ponds in 2012.

Today, Erikson says he focuses his energy on supporting nationalistic ideas and strict immigration laws. He believes there’s a direct link between the two.

“If we get more Islamic immigration we are going to get higher terrorism,” he said.

Erikson, United Patriots Front (UPF) leader Blair Cottrell and Chris Shortis, who also says he’s since dropped out of the group, made headlines in early September when they were found guilty of inciting serious contempt for Muslims. Two years earlier, a video posted on UPF’s Facebook page showed the trio beheading a dummy while chanting “Allahu Akbar,” Arabic for “God is great.” Cottrell and Erikson are appealing the conviction.

Erikson, who claims he left the UPF in late 2015, conceived the mock beheading to publicize a rally against a proposed mosque in Bendigo, north of Melbourne. He says he was well aware at the time that criminal charges could be laid. “As soon as we got charged with this we actually high-fived each other because it gave us a lot of publicity,” Erikson says. “I think it’s helped the patriot movement as a whole.”

The attention helped attract followers to the UPF on social media: by the time Facebook suspended their page and personal accounts in May, Erikson says the UPF had amassed 120,000 followers. CNN has been unable to verify that number.

These stunts highlight how the media is being used by extremists to fuel the rise of the Australian far right.

Journalist and author John Safran says it’s a movement with hundreds of thousands of followers that taps into ordinary people’s fears around Islam, gay marriage and the culture wars.

“I think they’ve worked out how to really latch on to what will get them in the press,” says Safran, who spent 18 months investigating Australia’s far-right subculture for his book “Depends What You Mean By Extremist.” He says some far right agitators appear to be asking themselves: “What are the issues the wider public is worried about and how do I weasel my way into the conversation?”

Renaissance began with a siege

The far right renaissance began with nationwide Reclaim Australia rallies in 2015, co-founded by Sydney mother Catherine Brennan who says she narrowly avoided being caught up in a 16-hour siege at a Sydney Cafe in December 2014. Known as the Lindt cafe siege, two people were killed and 18 others were held hostage by an Iranian-born gunman who demanded an ISIS flag.

Brennan, who was going to go to the café that day but didn’t due to a family emergency, soon began organizing rallies on Facebook to call for tougher immigration laws. The rallies generated enormous media attention.

“Without social media we wouldn’t exist, it’s that simple,” she says. “We would never have grown to almost 90,000 people in two years.” A number of far right groups, including the UPF, have followed.

The UPF considers itself a group of “nationalists” and “patriots,” without overt links to neo-Nazis, though in the past its leader Cottrell has backed giving Hitler’s Mein Kampf to every school student.

Safran believes some in the Australian far right cynically latch onto mainstream issues to get media attention – from the controversial Safe Schools program that aims to educate children about homophobia to fears that money raised in Halal certification supports terror groups.

“They might not care about an issue, but think ‘this will get me into the media.’ There’s mainstream acceptability to being anti-Muslim in a way there’s not in having a go at Aboriginal people or Jewish bankers.”

‘We’re in dangerous times’

In the last few weeks, the far right has found a new subject of debate in which to insert themselves: a national survey on whether to legalize same-sex marriage.

Shortis, the former UPF member, says the Yes lobby is bullying the No camp and “at the same time these degenerates play victim.”

“They are bringing in immoral practices that are anti-family … I find it offensive, their grotesque efforts to redefine the marriage act.”

Shortis tells CNN that issues like gay marriage, free speech and the call to tear down statues of colonists are “trigger points to reactions, they really are, and I think we’re in dangerous times.”

“If the politics of this nation continues to be increasingly progressive or radically progressive you are going to incite an opposite reaction, it’s that simple. The more radically left Australia … shifts, the more radical, as you would call (them) right, groups will arise,” Shortis said.

Neo-Nazi group Antipodean Resistance emerged recently to launch a homophobic offensive with a poster campaign linking same-sex marriage to pedophilia. On its website the Antipodean Resistance makes no attempt to hide its agenda and claims its members are “the Hitlers you’ve been waiting for.”

In response, opposition Attorney General, Mark Dreyfus called on Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to condemn neo-Nazi groups who were spreading false statements in the lead up to the vote.

“It’s an extraordinary thing that he’s just remained silent in the face of ugly statements that have been made in relation to the marriage equality survey,” Dreyfus said. Turnbull has thrown his support behind the yes campaign, and says he trusts that Australians can have a respectful discussion on the issue.

Last week, the Australian government passed new temporary laws to ban hate speech for the duration of the same-sex marriage vote. The new law threatens a $12,600 ($10,000) fine for people who vilify, intimidate or threaten harm “on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status or religion.”

Changing the conversation

Last May, Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, and Google said they would do more to identify and remove racist content and hate speech from their platforms.

Efforts to censor “hate groups” on social media have had mixed success. The UPF is practically defunct since it went offline in May but, according to Erikson, there are plans to resurrect it on Facebook.

However, Shortis says counting Facebook followers doesn’t accurately reflect the far right’s support.

“Likes on Facebook are not a true reflection of what movement exists out there. I think the movement is a lot more substantial,” Shortis says.

Actual numbers are hard to ascertain, but a report from Griffith University in Queensland earlier this year found right-wing extremism was on the rise.

Anti-fascist blogger Andy Fleming says there’s a big difference between posting racist comments online and actually hitting the streets. “The UPF page had 120,000 followers which is large, relatively speaking, but … they weren’t able to translate that to real life,” he says, pointing out their support peaked with 1,000 people attending the October 2015 rally against the Bendigo mosque.

A final appeal against the Bendigo Islamic Community Centre was thrown out of court last year, and construction of the $5.5 million (US$4.3 million) is set to begin.

Arguably the far right’s biggest success to date can be seen in the re-election of Pauline Hanson and three other One Nation party members to Australia’s Parliament. The far right politician, who held a seat in the House of Representatives in the 1990s, had garnered support for her anti-Asian views. Nearly two decades after leaving office, Hanson rode a wave of anti-Islam sentiment back into parliament in 2016.

Polling with around 15% of Queensland voters this year, One Nation could be a decisive factor in the upcoming state election. Another senator known for anti-Islamic views and support for US President Donald Trump, Cory Bernardi, defected from the ruling Liberal Party earlier this year to set up the Australian Conservatives.

The party opposes same-sex marriage, supports withdrawing from the UN Refugee Convention and wants to abolish the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Safran says by pushing itself into the mainstream media the far right is changing the national conversation.

“They get to put things up the flagpole and test out things that are more unsayable in the mainstream,” he says. “And they say it so much, these things become more normalized and less radical when Pauline Hanson or Cory Bernardi say it.”

Case in point: last month Hanson donned a burqa in parliament in a stunt calling for a ban on the Islamic garment in public. A week later a Sky News/ReachTEL poll was released showing 56.3% of Australians polled agree with her.

“This is just the beginning,” says Erikson. “The whole point of us doing this is to change the culture. Ten years ago you would never have had Pauline Hanson wear a burqa into Parliament, it would have been unheard of but … it seems normal now.”