Havana’s bustling nightlife went dark and silent as Cuba embarked on the post-Fidel Castro era.

The sale of alcohol was prohibited. Police and state security agents stood guard at street corners. During a long mourning period after Castro’s late November death, state-run television ran nonstop footage of his interminable speeches.

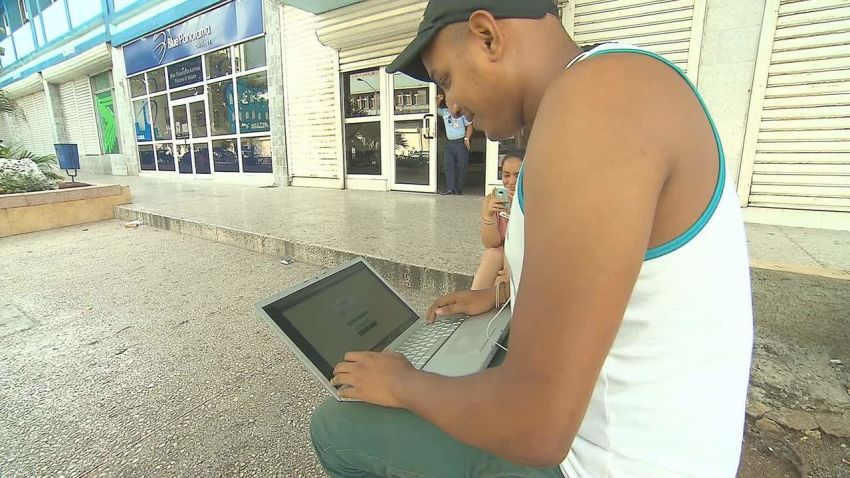

But outside of the Ambos Mundos Hotel in Old Havana – and at other Wi-Fi spots throughout the city – clusters of Cubans gathered to surf the Web.

Their faces illuminated by the screens on their devices, Cubans talked with family members and friends abroad. They laughed. Some cried. Others scrolled Facebook timelines – “liking” or commenting on photos and posts, catching up on news and gossip.

In a country in transition, such gatherings have become everyday occurrences. Similar scenes routinely play out at more than 100 Wi-Fi spots and parks set up by the government throughout the island, beginning in July 2015.

“We can’t drink rum, so we come here,” Raul Rossell, an engineer in his 50s, joked outside the Ambos Mundos, referring to the state-imposed alcohol ban.

For all its strides in health care and education, communist Cuba’s level of Internet connectivity is among the lowest in the world.

The island’s poor, outdated communications infrastructure has long conspired with the government’s deliberate decision to keep the majority of its more than 11 million citizens from surfing freely across the World Wide Web.

But Rossell and other Cubans believe that the longtime leader’s death – along with baby steps taken by brother and successor Raul to improve the information flow – will eventually free Cuba from its isolated corner of cyberspace.

Family Internet gatherings

Rosell’s son, Aniel, a 30-year-old teacher, said even five and six-year-olds at his school are becoming tech-savvy.

“They walk around with tablets and cellphones,” he said. “They take photos and shoot video with ease.”

Members of the Rossell clan, eight of them, stood outside the Ambos Mundos on a muggy night in what has become an almost weekly ritual.

Kevin Rossell, 10, chatted with his godmother in Spain. Later, he took a virtual tour of his aunt’s Miami home.

Another family member used the online time to preview clothing that would later be delivered to her by courier.

“We were laughing and looking at clothing and shoes,” Aniel Rossell said of the conversations.

“They were making fun of us, asking why was it so dark. They couldn’t see us. We’re in Cuba. There are no lights. We’re in the middle of the street.”

Critics have long complained that Cuban officials want to keep technology – and the open flow of information – out of their citizens’ hands.

The government has blamed the US trade embargo for the Internet drought.

Internet access is prohibitively expensive for most citizens, who survive on an average salary of about $20 a month. Many Internet users at state-run Wi-Fi parks buy access cards with money they receive from relatives abroad.

Cuba has made the Internet more accessible as part of the December 2014 agreement to begin normalizing relations with the US after a more than a half century of estrangement.

‘Looking to the future’

Aniel Rossell said many Cubans “have been looking to the future” in the two years since relations with the US began to thaw.

“This was the moment many of us had been waiting for,” he said. “Now both sides need to improve on that.”

The state has installed Chinese-made routers at dozens of parks and other locations around the country.

Users have to purchase $2, scratch-off cards that are good for an hour of Wi-Fi service. At many hotspots, entrepreneurs resell the cards at a higher price.

During President Barack Obama’s landmark visit to Havana in March, he appealed for greater freedoms on the island – including more Internet access for ordinary citizens.

In a historic address, Obama said sustainable economic growth and prosperity require more than just strong education systems, health care and environmental protections.

“It also depends on the free and open exchange of ideas,” Obama said. “If you can’t access information online, if you cannot be exposed to different points of view, you will not reach your full potential, and over time, the youth will lose hope.”

‘Destroy the revolution’

In 2015, Jose Ramón Machado Ventura, the second secretary of the Cuban Communist Party and first vice president of the Council of State, told state-run media that the cost of the Internet was partly to blame for its scarcity.

“Some want to give us it for free, so the Cuban people can communicate, but their real purpose is to infiltrate us … to destroy the revolution,” he warned.

One year earlier, Cuba freed American contractor Alan Gross, who was serving a 15-year sentence for bringing satellite communications equipment into Cuba.

The US State Department maintained Gross was an aid worker trying to help Cuba’s small Jewish community get online. Cuban authorities countered that he was part of a plot to destabilize the island’s single-party government.

An estimated 150,000 Cubans now have daily access to the Internet, up from 75,000 in 2014, according to Freedom House, a US nonprofit that promotes democracy.

Still, Cuba remains one of the least connected nations in the Western Hemisphere. Until 2008, the ownership of computer and DVD equipment was banned in Cuba. About 5% of the island’s homes are connected today, according to Amnesty International.

‘Technology can’t be stopped’

At a Wi-Fi (pronounced wee-fee in Spanish) spot at Monaco Park in Havana’s La Vibora neighborhood, Osiris Aleman sat uncomfortably at the foot of a tree.

She fidgeted with a tablet propped on her lap, typing a user name and password gleaned from a $2-an-hour Internet access card. But she failed to connect.

“I feel illiterate,” said Aleman, 55, who works at a travel agency.

She was trying to connect with her daughter, Thaeme, a doctoral student in Mexico.

“I get anxious at times,” said Aleman, who occasionally visits the parque Wi-Fi to chat for up to an hour as afternoon traffic hums along the streets. “I want to speak with her, to see her.”

“We talk about trivial things, about family and what she’s been doing,” said Aleman, who uses the Imo messaging program. “It’s cheaper than a phone call.”

She wishes there was more privacy.

“I get emotional sometimes,” she said. “That’s common with mothers who come here to speak with their children. You hear about their achievements and feel proud.”

Aleman was unable to connect after several tries, even as others around her spoke with loved ones abroad. The network appeared to be overloaded. She went home, leaving her chat for another day.

“We slowly adapt to conditions,” she said. “This is what we have for now… Technology can’t be stopped.”

‘Far from our reality’

Outside the Ambos Mundos Hotel, meanwhile, dozens of Cubans gather every night, holding smartphones and tablets.

“The Internet is opening up the world to younger Cubans,” Aniel Rossell said.

“We can finally meet relatives we never knew. We can reconnect with friends. We can see their pictures and how they’re living.”

His father Raul interjected, “Our Internet experience is still in its infancy.”

“Everything moves more slowly here,” Aniel Rossell said.

Nearby, Jose Luis Rodriguez, 33, held the camera flash of his cell phone over his mother’s head as she chatted on a tablet with a sister in Miami.

Rodriguez made a joke about drinking aged rum during Castro’s mourning period. His mother talked about winning a local lottery, buying a Cristal beer and Wi-Fi card on the black market. She complained about the weak Internet signal and other scarcity on the island.

“We look into the tablet and what we see … is far from our reality,” Rodriguez said.