Story highlights

Catalonia is home to world's largest concentration of millenary olive trees

The 1,700-year-old Farga de l'Arión might be the world's oldest olive tree

It’s a sight that’s been greeting travelers for thousands of years.

On the Montsià plains of southern Catalonia, about a two-hour drive south of Barcelona, lies the Mar de Olivas, or Sea of Olives. Here, shielded between two small mountain ranges, in a broad dry valley near the mouth of the Ebro River, olive groves stretch as far as the eye can see.

And not just any olive trees: This area hosts the largest concentration of millenary olive trees not just in Spain but anywhere in the world.

To qualify as one of these ancient olive trees, the diameter of the trunk has to be more than 3.5 meters, measured at a height of 1.3 meters from the ground. More than 4,400 trees thought to be 1,000 years or older have already been located and cataloged, while many more may be waiting to be discovered.

With most of these trees still producing oil, customers worldwide are developing a new taste for this ancient flavor.

The oldest olive tree in the world

Near the small town of Ulldecona, is a unique piece of natural heritage: a 1,700-year old tree which might be the oldest, scientifically dated, olive tree anywhere in the world.

Researchers at the Technical University of Madrid used advanced laser-based techniques to conclusively date the Farga de l’Arión, as this monumental tree is called, to the early fourth century.

This was during the reign of Roman emperor Constantine the Great, who ruled over Britain, Gaul and Spain. Most of the ancient trees here are of the Farga variety, a heirloom olive that is endemic to the area.

“It is difficult to find a Farga olive tree that is younger than 200 years old,” explains Jaume Antich, former mayor of Ulldecona and now an adviser at Taula del Senia, which works to preserve the trees’ heritage and promote tourism.

“They tend to be less productive than other varieties, therefore they went out of favor for a really long time.”

Valuable asset

Until very recently, Antich explains, Farga olive trees were felled and replaced with higher-yielding varieties, or simply uprooted and resold elsewhere as garden decor.

However, most millenary trees are still productive. The growing popularity of the Mediterranean diet and increasing consumer interest in food provenance have opened up new opportunities for olive oil entrepreneurs.

“It is only recently that we realized that we had a valuable asset in these trees, that people are ready to pay for the experience of tasting an olive oil with such a unique origin,” says Antich.

Amador Peset used to work as a carpenter, but when Spain’s construction boom ended a few years ago, the 37-year-old switched to making olive oil.

Recognizing the potential of ancient olive trees, he launched his own brand of millenary oil: Thiarjulia, named after the Roman name of his hometown of Traiguera.

The tree-finder

Having begun with his own small plot of millenary trees, Peset now drives around the region finding other ancient trees that are being neglected by the landowners.

He then will usually make an arrangement with the owners so he can harvest specific trees for his Thiarjulia brand.

“It has become like an obsession,” he says. “I love to find these trees and bring them back into production.”

His annual yield of millenary olive oil is around 800 liters, harvested from more than a hundred scattered trees.

That’s a tiny drop in the ocean of Spanish olive oil production, which in 2015/16 stood at 1.4 million metric tons, or close to half the total global olive oil production.

However, Peset has still found a lucrative market for his oil in China and other Asian countries. His 100ml bottles of saffron-infused millenary oil are not only consumed at the table, but sold for cosmetic use too.

Another nine local producers are also in the millenary olive oil business, each with their own brand. A certification scheme has also been created in order to guarantee the provenance of millenary olive oils and underpin its image in consumer markets.

Olive grove tours

A walk through the Arión estate’s open-air museum, where the alleged world’s oldest olive tree is located, gives you an idea why these groves are drawing a still rather small, but growing, crowd.

The centuries have left their mark on these monumental trees, turning their wide, robust and contorted trunks into proper living sculptures.

Every one of them is unique in its own way, while contributing to a harmonious whole.

A tour of the olive groves can be easily complemented by visiting the remains of one of the nearby cliff-top Iberian settlements dating back to around 600 BC.

Moleta del Remei

At the most well preserved of these, the archaeological site at Moleta del Remei, it’s possible to imagine how life was for the inhabitants of those lands 2,600 years ago.

This was well before the arrival of Romans and Carthaginians made this region a battleground in their struggle for Mediterranean hegemony.

The navies of these two superpowers of antiquity clashed within sight of the village in the decisive Battle of Ebro River in 217 BC.

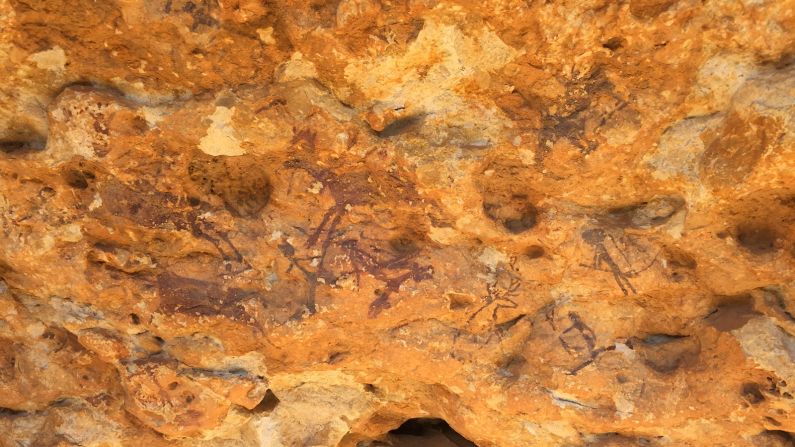

Those looking for even older artifacts can’t miss the cave paintings at nearby Serra de Godall.

Here, some 8,000 years ago, groups of huntsmen left their pictorial mark in a series of open rock shelters. The amazing hunting scenes, one of the few sites in Mediterranean cave art to feature women, are clearly visible to the naked eye and accessible for close-up inspection.

As you can see, even the oldest of the trees can look young next to some of the heritage surrounding them.

By claiming back their ancient olive trees, though, the inhabitants of this little-visited corner of the Mediterranean are not only tapping a sustainable economic resource, but re-establishing a direct link with this remote past.

How to get there

Ulldecona

Although it’s possible to reach Ulldecona by train, we recommend traveling by car. The local train service is infrequent and the various sites of interest are scattered around a a radius of several kilometers from the town center.

From the AP-7 motorway (Barcelona-Valencia), follow exit 42, then road T-332 for around five kilometers.

Guided tours of millenary olive trees can be booked at Ulldecona Tourist Information Office.

The standard package costs 10 euroes (around $11) per person and includes a guided visit to the Airón Estate millenary olives open-air museum (accessible only as part of a guided tour), Ulldecona’s medieval castle and the Serra de Godall cave paintings.

Local millenary oils are also for sale at the Tourist Office.

Turisme Ulldecona; Passeig de l’Estació, s/n, 43550 Ulldecona, Catalonia, Spain; +34977573394

The oils can also be tried at the Michelin-starred Les Moles and L’Antic Molí restaurants in Ulldecona.

Les Moles; Carretera de La Sènia km 2, 43550 Ulldecona; +34977573224

L’Antic Molí; Barri Castell, 43559 El Castell, Ulldecona; +34977570893

Serra de Godall and Moleta del Remei

To visit the cave paintings, head to Centre d’interpretació d’Art Rupestre, next to Ermita de la Pietat. Follow the road from Ulldecona to Tortosa for around four kilometers.

It’s advisable to book in advance, either by calling +34653937204 or through Ulldecona Tourist Office.

Centre d’interpretació d’Art Rupestre; C. de la Pedrera, Ulldecona, Tarragona

To reach the archaeological settlement of Moleta del Remei, follow the road from Ulldecona to Alcanar for about two kilometers. Guided tours can be booked through Ulldecona Tourist Office.

Moleta del Remei; 43530 Alcanar, Catalonia, Spain; +34977737639