Some of the victims can't speak. They rely on walkers and wheelchairs to leave their beds. They have been robbed of their memories. They come to nursing homes to be cared for.

Instead, they are sexually assaulted.

A CNN Investigation

Six women. Three nursing homes. And the man accused of rape and abuse

Luis Gomez appeared to many to be the perfect nursing aide. He loved his job and went the distance for residents in his care. But now a different image has emerged: Gomez, who insists he is innocent, is accused of being a serial abuser -- moving from facility to facility despite a history of allegations against him. CNN documents his trail.

Opinion

My mother was raped at 88

A daughter describes the resilience that helped her family not only heal but fight for reform.

The unthinkable is happening at facilities throughout the country: Vulnerable seniors are being raped and sexually abused by the very people paid to care for them.

It's impossible to know just how many victims are out there. But through an exclusive analysis of state and federal data and interviews with experts, regulators and the families of victims, CNN has found that this little-discussed issue is more widespread than anyone would imagine.

Even more disturbing: In many cases, nursing homes and the government officials who oversee them are doing little -- or nothing -- to stop it.

Sometimes pure -- and even willful -- negligence is at work. In other instances, nursing home employees and administrators are hamstrung in their efforts to protect victims who can't remember exactly what happened to them or even identify their perpetrators.

In cases reviewed by CNN, victims and their families were failed at every stage. Nursing homes were slow to investigate and report allegations because of a reluctance to believe the accusations -- or a desire to hide them. Police viewed the claims as unlikely at the outset, dismissing potential victims because of failing memories or jumbled allegations. And because of the high bar set for substantiating abuse, state regulators failed to flag patterns of repeated allegations against a single caregiver.

It's these systemic failures that make it especially hard for victims to get justice -- and even easier for perpetrators to get away with their crimes.

"At 83 years old, unable to speak, unable to fight back, she was even more vulnerable than she was as a little girl fleeing her homeland. In fact, she was as vulnerable as an infant when she was raped. The dignity which she always displayed during her life, which was already being assaulted so unrelentingly by Alzheimer's disease, was dealt a final devastating blow by this man. The horrific irony is not lost upon me ... that the very thing she feared most as a young girl fleeing her homeland happened to her in the final, most vulnerable days of her life."

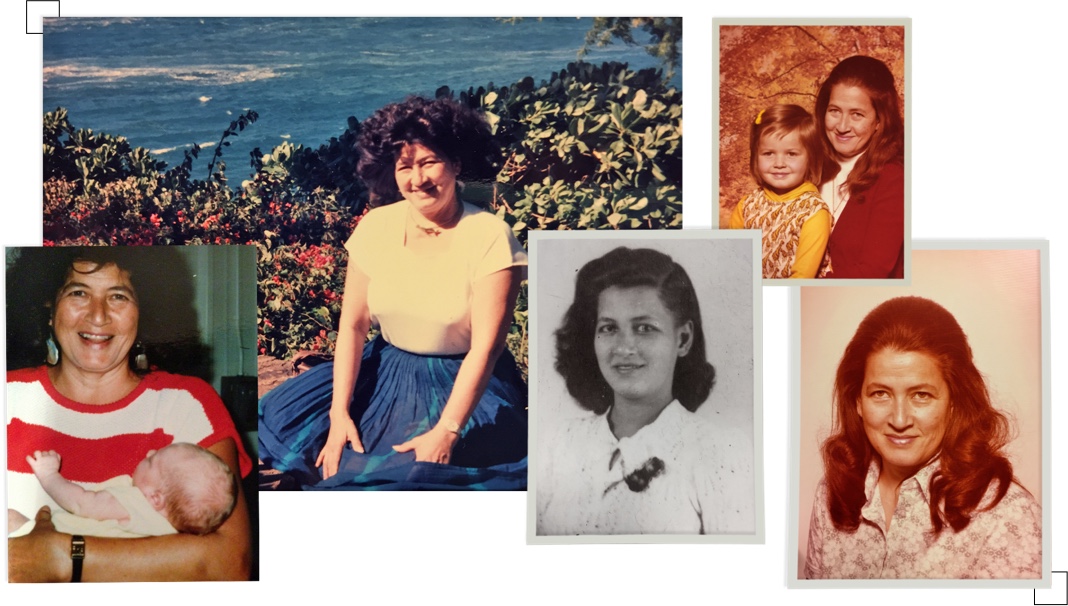

Sonja Fischer is shown here in earlier days. She is pictured at top of this story during the last years of her life, with her daughter Maya's haunting quote.

Maya Fischer made this statement in court at the 2015 sentencing of a nursing assistant convicted of raping her mother. Choking back tears, Fischer detailed her mother's story -- recounting how she had fled Indonesia as a youth with her family to escape the rape and killing of young girls by Japanese soldiers, only to fall victim decades later to a man whose job was to care for her.

A fellow caregiver saw male nursing assistant George Kpingbah in 83-year-old Sonja Fischer's room at 4:30 a.m. on December 18, 2014, at the Walker Methodist Health Center in Minneapolis. A bare leg was on each side of his hips, and her adult diaper lay open on the bed. When the witness noticed the 76-year-old aide thrusting back and forth, she said she knew a sexual assault was occurring.

Kpingbah ultimately pleaded guilty to third-degree criminal sexual conduct with a mentally impaired or helpless victim and was sentenced to eight years in prison. In an emotional statement directed at Kpingbah during sentencing, the judge told him he had done more than ravage the lives of his victim and her family. He had betrayed the public trust granted to caregivers who have such intimate access to the sick and elderly.

"You violated (a) position of authority, a position of trust," Judge Elizabeth Cutter said at the sentencing hearing. "The ramifications of what you did are so far-reaching. ... It also affected everyone in that facility. Everyone who stays in that facility. Everyone who works at that facility. It affects everyone who has to place a loved one in a facility."

Kpingbah apologized at the hearing and said he planned to take his Bible with him to prison. His attorney asked for leniency. Kpingbah had endured his own personal struggles as a refugee, the attorney said, fleeing Liberia after many of his family members were killed. Kpingbah's one "unspeakable act," he told the judge, was completely out of character.

Yet in court documents uncovered by CNN, prosecutors revealed it wasn't the first time Kpingbah had been investigated over sexual assault allegations. Personnel records obtained by prosecutors during the investigation and reviewed by CNN show Kpingbah was suspended three times as Walker Methodist officials investigated repeated accusations of sexual abuse at the facility, including at least two where he was the main suspect.

The earliest complaint was in 2008, when police investigated allegations he had engaged in sexual intercourse with a 65-year-old who suffered from multiple sclerosis. In another case, an 83-year-old blind and deaf woman who lived on the same wing as Fischer's mother said she was raped multiple times -- always at midnight. Police investigated her report just seven months before Fischer's mother was assaulted. While the woman could not identify her assailant, Kpingbah was suspended by the facility along with several other male staffers who were on duty during the nights of the alleged assaults.

None of these allegations were found to be substantiated by the facility or the state. For years, Walker Methodist kept Kpingbah working on the overnight shift. Until that early morning in December 2014, when someone caught him in the act.

In that instance, the Minnesota Department of Health found that the facility acted immediately to ensure the resident's safety and promptly removed Kpingbah. The state also noted that the facility had previously provided Kpingbah with required abuse training. As a result, the facility was not cited for any wrongdoing; only Kpingbah was held accountable for the assault.

Maya Fischer had no way of knowing about the previous allegations against Kpingbah uncovered by CNN. But she sued Kpingbah, who agreed to an unusual arrangement in which he is on the hook for a massive $15 million judgment only if he abuses again.

Walker Methodist refused to comment on the previous allegations against Kpingbah, who worked at the facility for nearly eight years, but said in a statement that it fully cooperated with authorities and that "the care and well-being of all of our residents and patients is our primary focus."

CNN reached out to family members of other residents who earlier reported they were sexually assaulted at Walker Methodist during the time Kpingbah worked there (though he was not deemed a suspect in every case). They said the officials there were quick to dismiss the residents' claims as hallucinations or fantasies.

What should we investigate next? Email us.

"Walker Methodist certainly failed to handle this appropriately with my mother and other residents, and there should be consequences," said the son of the first alleged victim after learning of Kpingbah's rape conviction from CNN.

A son of a different alleged victim, who had accused an unknown perpetrator, said he was irate he was never told that a pattern of complaints had emerged against a single caregiver. Had he known of this pattern, the son said, he would have taken his mother's report of abuse more seriously. Instead, he trusted Walker Methodist.

The Minnesota Department of Health told CNN it is barred by state law from releasing the identity of anyone investigated over an allegation that has not been substantiated, regardless of the number of allegations.

But both family members of these two alleged sexual assault victims also questioned the state health department. How effective is its oversight if it was aware of the multiple reports of abuse at Walker Methodist and still could not intervene?

When pressed by CNN, the agency said that the reports occurred during a time when a paper system was used and that it has been working to modernize this system in the hopes of "flagging such patterns."

A daughter's heartbreaking story

Abuse after abuse

Some accounts of alleged sexual abuse come from civil and criminal court documents filed against nursing homes, assisted living facilities and individuals who work there. Other incidents are buried in detailed reports filed by state health investigators.

A 76-pound North Carolina nursing home resident who was so cognitively impaired she required assistance with even the simplest daily tasks reported that a nursing aide, behind closed doors, pushed her head toward him and forced her to give him oral sex.

The third time a resident of a Texas nursing home was raped by a nurse, the assailant ejaculated in the victim's mouth and on her breasts. When he left, desperate to hold on to whatever evidence she could, she spit the semen from her mouth into her bra and kept the unwashed bra for three weeks. "That's all I have," she later told state investigators.

In Iowa, a woman who depended on a walker to move around and couldn't bathe herself reported that a nursing aide sexually assaulted her in the shower. But the facility never flagged this accusation to authorities because the aide had left the country.

An 88-year-old California woman who'd only had sex with one man her entire life -- her husband of nearly 70 years -- said she awoke in her nursing home bed with her catheter removed and her bed wet. The next thing she remembered was seeing an unknown male nursing assistant staring at her naked body. "This is why I love my job," she remembered him saying, according to what she told police. Weeks later, the woman complained of severe vaginal pain and "oozing blisters," and she was eventually diagnosed with incurable genital herpes. To this day, the identity of the alleged perpetrator hasn't been determined.

And finally, in a small town in North Carolina, a nursing assistant continued working for years despite multiple reports of alleged abuse. Only after a defiant nurse reported the abuse to police was he fired and arrested. Luis Gomez, 58, is in jail awaiting trial and maintains his innocence.

Most of the cases examined by CNN involved lone actors. But in some cases, a mob mentality fueled the abuse. And it's not just women who have been victimized.

CNN found more than 1,000 nursing homes have been cited for mishandling suspected cases of sex abuse.

For months, a group of male nursing aides at a California facility abused and humiliated five male residents -- taking videos and photos to share with other staff members. One victim, a 56-year-old with cerebral palsy, was paraded around naked. Another, an elderly man with paralysis who struggled to speak was pinched on his nipples and penis and forced to eat feces out of his adult diapers. He was terrified his abusers would kill him. While the aides lost their certifications, an investigation by Disability Rights California found that many of them never faced charges.

Another group of nursing aides, teenagers in Albert Lea, Minnesota, tormented at least 15 male and female residents, many of whom suffered from Alzheimer's. The female aides struck, poked and rubbed the residents and touched their breasts. They inserted their fingers into one resident's rectum. They rubbed the residents' crotches and laughed. One aide pulled down her own pants and sat on a female resident's lap -- humping and groping her. "I was basically appalled by the callous disregard for human decency," a judge later said. Two of the abusers, who were 18 at the time and convicted of disorderly conduct by a caregiver, served 42 days in jail. The other teens were tried in juvenile court and faced no jail time at all.

An untracked issue

Despite the litany of abuses detailed in government reports, there is no comprehensive, national data on how many cases of sexual abuse have been reported in facilities housing the elderly.

State health investigators examine all types of abuse reported at nursing homes and assisted living facilities, whether reported by the facilities or flagged by complaints to the state from witnesses, family members or victims. In the case of nursing homes, state officials typically conduct these investigations, as well as routine inspections, on behalf of the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which regulates the more than 15,000 facilities that receive government reimbursements that pay for many residents' care. Both state health agencies and the federal government then use the information to rate facilities and issue financial penalties for the worst offenders.

How safe are your elderly loved ones?

There’s no way to know about abuse that goes unreported. But you can look up the name of a nursing home in federal inspection data and see whether it has been cited for sexual abuse or other issues in the past three years. Here's how:

- Go to the federal Nursing Home Compare website to look up facilities by name or location.

- On the first page of results, you will see a star rating for the facility based on factors such as staffing levels. A history of abuse or other inspection problems will typically be reflected in the "health inspection" rating.

- Click on the health inspection rating to see a summary of the facility's most recent inspection.

- From here, click on "View all health inspections." For details, go to a specific date and click "View full report."

- From the main profile page for the facility, click on "Penalties" to see if an inspection resulted in fines or payment denials.

- To view older citations, download archived reports here or file a public records request here. Some states may also offer detailed information. A list of state websites is here.

CNN surveyed the health departments and other agencies that oversee long-term care facilities in all 50 states. Of the states that could provide at least some data, the responses varied widely.

Illinois, for example, said 386 allegations of sexual abuse of nursing home residents had been recorded since 2013, 201 of which involved a caretaker. Hawaii said eight allegations of sexual abuse were investigated between 2011 and 2015 -- five of which involved a caregiver. And when states provided a further breakdown of how many allegations had been substantiated, the results demonstrate just how few accusations end up being proven -- whether it's because of the extreme hurdles posed by aging victims, the destruction of evidence or half-hearted investigations by facilities and regulators.

Of the 386 cases in Illinois, 59 were considered substantiated. And in Texas, 11 of 251 sexual complaints in the 2015 fiscal year were substantiated. Wisconsin said it didn't have a single substantiated report of abuse in the last five years.

But most states could not say how frequently abuse investigations involved sexual allegations, often stating that sex abuse allegations are not categorized separately from other forms of abuse.

The federal government doesn't specifically track all sexual allegations either.

More than 16,000 complaints of sexual abuse have been reported since 2000 in long-term care facilities (which include both nursing homes and assisted living facilities), according to federal data housed by the Administration for Community Living. But agency officials warned that this figure doesn't capture everything -- only those cases in which state long-term care ombudsmen (who act as advocates for facility residents) were somehow involved in resolving the complaints.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services lumps sexual allegations into a category that includes all kinds of abuse, such as physical or financial. The agency said this is because it takes all forms of abuse seriously. When asked by CNN, the agency conducted a specialized search using sex-related keywords. But because not every case was sexual in nature, CNN had to review each case individually to filter out any irrelevant citations.

The reports show that 226 nursing homes have been cited for failing to protect residents from instances in which sexual abuse was substantiated between 2010 and 2015. Of these cases, around 60% resulted in fines, which totaled more than $9 million -- though only 16 facilities were permanently cut off from Medicare and Medicaid funding. (Because the federal government only regulates nursing homes, this analysis did not include assisted living facilities.)

But these statistics only tell a small part of the story because they fail to capture the many instances in which nursing homes have been cited for mishandling allegations of sexual abuse in other ways -- ranging from botched investigations to cover-ups.

Using inspection reports filed between 2013 and 2016 and a similar sex-related keyword search, CNN conducted its own detailed analysis.

The result: CNN exclusively found that the federal government has cited more than 1,000 nursing homes for mishandling or failing to prevent alleged cases of rape, sexual assault and sexual abuse at their facilities during this period. (This includes some of the cases provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.) And nearly 100 of these facilities have been cited multiple times during the same period.

Complaints and allegations that don't result in a citation, which the government calls a "deficiency," aren't included in these Medicare reports. In addition, national studies have found that a large percentage of rape victims typically never report their assaults. So these numbers likely represent only a fraction of the alleged sexual abuse incidents in nursing homes nationwide.

Want to know how we did this? Click here for information.

Our analysis

CNN began its in-depth analysis by obtaining federal inspection reports filed between 2013 and 2016. These reports are filed by state health inspectors working in conjunction with the federal government for the more than 15,000 nursing homes that receive Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements. They include complaints and allegations where state inspectors have cited a facility for failing to meet a wide variety of federal standards, whether it is storing food improperly or serious allegations of abuse or neglect.

For CNN's analysis, these reports were narrowed down using a specific set of sex-related keywords. But because many citations included information about intimate medical care and not abuse, CNN reporters read more than 6,000 citations to identify only those related to allegations of sexual assault or abuse. During this analysis, the reporters also categorized allegations based on the severity of abuse and the kind of perpetrator (whether a caregiver, resident or visitor), among other data points. At the end of this weeks-long analysis, CNN concluded that more than 1,000 nursing homes across the country have been cited for somehow mishandling or failing to prevent alleged cases of sexual assault at their facilities in recent years.

Of the instances examined, at least a quarter were allegedly perpetrated by aides, nurses and other staff members, while a small portion involved facility visitors (including family members) or unknown assailants. And while most citations dealt with cases of residents abusing other residents, accusations made about caregivers and other workers tended to be far more serious, involving allegations of forced intercourse, oral sex, digital penetration and other forms of sexual assault.

The stories found in these reports range from sad to sickening.

An aide admitted to urinating in the shower while a female resident was inside it, showing her his erect penis and kissing her -- then warning her not to tell anyone. A nurse overheard two aides talking about how a resident had been given a lap dance that made him ejaculate. A woman was found gagging and trying to fight off a male resident who had his penis in her mouth. Family members viewed video footage of an aide repeatedly raping their loved one, who was on feeding tubes, after hiding a camera in a stuffed animal in the room.

CNN's analysis found that the nursing homes themselves are a large part of the problem. More than 500 facilities had been cited for failing to investigate and report allegations of sexual abuse thoroughly to authorities or for not properly screening employees for potentially abusive pasts. One nursing director told a state inspector that "if the facility reported all allegations it would be numerous and the State Agency wouldn't want that either."

Because of this lack of investigation or reporting, it's hard to determine how many of the alleged cases of abuse were substantiated or resulted in criminal proceedings. But at least several hundred were confessed to by the perpetrators or observed by witnesses.

Amid the reports of sexual abuse were hundreds of stories that painted scenes of chaos:

Residents climbing into other residents' beds and eating their food. Running wildly up and down halls. Pulling out knives and other weapons. Hallucinating about snakes coming out of heads and little boys hiding in the curtains. Urinating in wastebaskets. Drinking and doing drugs. Falling asleep in the bathtub. Stealing walkers. Choking and hitting people with fists and wheelchair parts. Escaping out windows. Drinking lotion and oven cleaner.

Such a challenging environment provides some context for how serious allegations of sexual assault could be overlooked.

An unchecked 'epidemic'

It's rarely talked about, but sexual assault in the very facilities tasked with caring for the elderly is hardly a new problem, with cases dating back decades.

It's happening all over the country. In cities, the suburbs and the countryside. In nursing homes housing low-income residents on Medicaid. And in centers where people pay thousands of dollars out of their own savings to be there. They're owned by huge corporations and regional chains but also by nonprofits and mom-and-pop small business owners.

And the issue is only becoming more pressing as the elderly population booms, with the number of Americans over age 65 projected to more than double between 2010 and 2050.

Sign up to receive updates on this and other CNN investigations

Yet the facilities that currently house more than 1 million senior citizens typically pay low wages to nursing assistants (about $11 or $12 an hour), making it difficult to attract and keep quality workers. And during the most vulnerable hours, the night shift, there are often few supervisors.

The abuse is "an epidemic," said Mark Kosieradzki, a Minnesota attorney who has represented a number of victims and their families, including Fischer, the woman who recounted her mother's rape in court. "Predators find elderly patients to be easy prey. Those patients often have dementia. They can't say what happened, or are not believed because many people find it inconceivable that a 28-year-old caregiver would want to rape someone's grandmother."

Kosieradzki and other experts who advocate on behalf of the elderly say strong federal and state laws are in place that require abuses to be reported and investigated. The problem, they say, is that these laws are not always followed by the nursing homes. And while federal and state officials told CNN that regulators aggressively investigate complaints and hold facilities accountable, critics say their enforcement isn't tough enough. And investigations by facility and state officials are often cursory at best, rarely going deep enough to meet a difficult burden of proof.

Many nursing home employees promptly report abusers to authorities as required by federal law and assist in the investigations. But in numerous examples of abuse uncovered by CNN, the facilities themselves have made it possible for violent rapes and sexual assaults to go unchecked.

In these facilities, allegations are routinely questioned or dismissed because victims have cognitive conditions such as Alzheimer's. Workers often lack the specific training needed to spot sexual abuse -- keeping reports of abuse from ever reaching authorities. And the reputation and safety of the facility may take priority: There's often a fear that bringing investigators into a cash-strapped facility may expose other issues, threaten a nursing home with closure or open the door to costly lawsuits.

Most sinister of all are administrators and employees who actively impede investigations.

"There are some situations where they don't realize it's happened, and they don't want to believe it. They just don't understand it," said Ann Burgess, a well-known nurse and Boston College nursing professor who specializes in the assessment and treatment of elderly sexual abuse victims. "There are other cases where they try to cover it up. ... They blame the victim."

At one Colorado facility, nursing aide Antonio Nieto had already been accused of raping one female resident in her bed at Broomfield Skilled Nursing & Rehabilitation Center when an allegation emerged from another woman. Prosecutors say the facility allowed Nieto to return to work after the first alleged assault because the facility had found the woman's claims to be "unfounded." The facility, which has come under new management since the assaults, said it allowed Nieto to return to work only after being told the police investigation had stalled and no criminal charges were expected.

He was fired after the other victim came forward. Nieto was ultimately sentenced to 24 years to life in prison. Broomfield paid a $51,837 fine, a paltry sum in comparison with the millions it received in annual government reimbursements for patient care.

Nursing assistants Andrew Merzwski, from left, Antonio Nieto and George Kpingbah were all convicted of raping elderly residents.

When the chef at an assisted living facility, was arrested in Louisiana last year in the alleged rape of a 78-year-old resident, a director at the facility, Julie Henry, was quick to issue an emotional statement to local media -- claiming the company was "shocked and disheartened." But not long after, Henry was arrested, accused of orchestrating an elaborate cover-up of the abuse. According to police, she had tried to prevent an investigation by instructing staff not to report the incident. She asked employees at the assisted living facility, Beau Provence Memory Care, to hand over all evidence to her, which she then allegedly destroyed. The chef, Jerry Kan, was indicted on a first first-degree rape charge and has pleaded not guilty. The case is ongoing and his attorney declined to comment.

Henry has not been indicted, and her case is under review. Henry's attorney said he is confident the continued investigation will result in her exoneration. "The resident and the cook, Mr. Kan, initially denied anything had occurred, creating confusion as to whether this was a reportable incident. When it was learned that an incident had occurred, Ms. Henry cooperated fully with the police and continues to do so," he said in an email. Beau Provence said it was working with police and the state health department to "verify the facts behind these allegations," but said it could not comment further on an ongoing investigation.

Even in facilities where there were no allegations of an orchestrated cover-up, documents examined by CNN showed a failure to preserve evidence. A resident who alleged abuse would be given a shower, for instance, or the crime scene might be disturbed by the washing of bedsheets. As a result, possible DNA evidence was lost.

In Minnesota, officials transferred an 89-year-old resident at the Edgewood Vista assisted living facility to the psychiatric ward of a local hospital after she reported being raped. A certified nursing assistant, Andrew Merzwski, 28, admitted to having sex with the resident but claimed it was consensual. A director at the facility believed him and blamed the victim -- who suffered from dementia -- telling the sexual assault nurse who examined the victim that the resident was a "flirt."

"She (had) come forward and spoken out against her facility and she was locked in a room," the nurse examiner, Theresa Flesvig, told CNN. "She felt like she was in prison. She felt like she was being punished." Her rape examination didn't occur until almost a week after the alleged assault. Flesvig said she discovered clear physical evidence of assault, one of the largest vaginal tears she had ever seen. Merzwski pleaded guilty to criminal sexual conduct and was sentenced in 2014 to 53 months in prison, while the state disciplined the official who had sided with him. Merzwski's attorney declined to comment.

The facility said it couldn't comment on details of the specific case, citing privacy reasons, but did acknowledge that officials had learned from the incident. "What we learned was we weren't prepared for anything of this nature," said Michael Johnson, chief nursing officer for Edgewood Management Group. "We had to do better."

Sometimes police and state investigators also fail to take complaints seriously. In one instance, a police report reviewed by CNN cited an administrator's statement that the victim was an "avid viewer of the television show 'Law and Order'" as a reason to dismiss her allegation. "Hallucinations seem to revolve around episodes of the series," the officer wrote. As a result, there were no arrests, the rape kit was not tested and the case was closed.

Inside the mind of a nursing home rapist

"The 'victim' of this investigation has made similar allegations regarding suspects that do not exist, are physically unable to have committed the act she accuses, etc.," the police department told CNN in a written statement. "The 'victim' suffers from mental illness and hallucinations, her statements are inconsistent and unfounded."

In the Minnesota case involving nursing aide Kpingbah, the state investigator wrote that the first alleged victim had a "lengthy history of falsely accusing male caregivers of sexual inappropriateness" and "sexual promiscuity and inappropriate boundaries." When CNN showed this victim's son the state's report, he said the characterizations were false.

Asked about this by CNN, the Minnesota Department of Health said the claims had been taken seriously and investigated. "In hindsight and according to current report writing practices, MDH regrets the wording of this statement and apologizes to the family for this insensitive statement," the agency said.

While assailants such as Kpingbah have ended up behind bars as a result of their crimes, many never face charges.

The older the victim, the less likely an offender will be convicted of sexual abuse, according to a study of the elderly sponsored by the National Institute of Justice. And victims who lived in facilities were even less likely to see their assailants face charges and guilty verdicts.

In fact, victims with dementia and other diseases are often considered such unreliable witnesses that even cases in which an assailant confesses to the crime can end up being thrown out or result in little punishment for the defendant. That was true in the case of Walter Martinez, a St. Louis nursing aide who faced felony rape charges and years in prison after confessing in a resignation letter to abusing two elderly residents sexually. Martinez ended up receiving two years of probation after the alleged victims died or suffered from such severe dementia that they weren't able to testify.

His attorney told CNN that despite the resignation letter, Martinez had never pleaded guilty to the conduct he was charged with and was prepared to defend himself in court. "Mr. Martinez had gone to counseling and admitted that he had sexual thoughts while performing his regular job duties. He felt tremendous guilt for having these thoughts and that is when he used the term 'sexual abuse' in his resignation letter," he said in an email.

In the case of the Texas woman who saved her bra for weeks as evidence, a suspect was arrested and indicted in the alleged rape. But court records show that prosecutors couldn't secure the alleged victim's testimony. The case was dismissed last year despite the fact the DNA from the bra matched a sample taken from the accused. The lab said the chances of the DNA being from anyone else was less than 1 in 983 trillion.

Even those facilities that actively impede investigations or cover up abuse often get little more than a slap on the wrist. The vast majority of nursing homes with horror stories chronicled in the inspection reports are still in business, accepting new residents today.

"How hard is it to shut one down? It is almost impossible," said Tony Chicotel, a staff attorney at the nonprofit group California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. "The worst nightmare for the state regulators is a facility closing -- because the residents oftentimes have no place to go."

So instead, government regulators levy fines and withhold Medicare and Medicaid payments in the hope of getting facilities in line. But even when penalties are imposed, which the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services says are meant to push a facility to correct a given issue as soon as possible, the fines are often shockingly small.

When a facility in Texas failed to take proper action after an elderly man said he was raped and drugged, authorities punished the home with a $116,500 fine and by temporarily banning it from receiving government reimbursements for new patients. But the fine was ultimately cut almost in half, based on the facility's "financial hardship." And the ban lasted only 11 days.

A facility in California -- which allowed a licensed nurse to work for weeks despite reports he had sexually assaulted a female resident multiple times, kissing her and fondling her breasts -- was fined $22,000 by the state.

And then there is Walker Methodist in Minnesota, where 83-year-old Sonja Fischer became the victim of the same kind of violent assault she had fled so many years ago. There she was raped by an employee the facility knew had been the subject of abuse allegations for years.

"She was unable to speak, unable to move," her daughter Maya recounted just a few weeks after her mother passed away last year. "She couldn't even cry out when this was happening to her."

The facility where she was victimized received no penalty at all.

CNN's Ana Cabrera, Sara Weisfeldt, David Heath, Sergio Hernandez and Andrew Bloomenthal contributed to this report.

Published on February 22, 2017