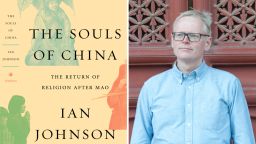

Editor’s Note: Ian Johnson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent based in Beijing. His new book, “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao,” will be published in April. The views expressed below are solely his own.

Story highlights

Freedom House report says religious oppression in China has "intensified"

Johnson: This analysis misses the huge spiritual revival ongoing in the country

How bad is religious persecution in China?

This is a question I’ve thought a lot about over the past few years. Since 2010 I’ve been working on a project documenting a religious revival in China, and seen new churches, temples, and mosques open each year, attracting millions of new worshipers.

But I’ve also seen how religion is tightly proscribed.

Only five religious groups are allowed to exist in China: Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Protestantism and Catholicism. The government controls the appointment of major religious figures, and decides where places of worship can be built. It tries to influence theology and limits contacts overseas. And it bans groups it doesn’t like, especially the spiritual practice Falun Gong, or groups it calls cults, like the charismatic Christian splinter sect Almighty God.

As atheist China warms to the Vatican, religious persecution ‘intensifies’

These problems are explained in a new and carefully researched study by Freedom House. The 142-page report, “The Battle for China’s Spirit,” points out that some religions face little persecution. Daoists and Buddhists are faring well, while Catholics could soon enjoy better times, with ties possibly warming between Beijing and the Vatican.

But overall, the message is glum. Almost all groups are said to face serious restrictions, with three groups –Uyghurs who practice Islam, Protestant Christians, and followers of the banned spiritual practice Falun Gong –facing “high” or “very high” levels of government interference.

Cross-removals

While most of the facts in the study are correct, the context feels more negative than the religious world I’ve experienced. Of course it is in the nature of such reports to be critical –this is what watchdogs like Freedom House are for– but it feeds into an overall assumption in western countries that the Chinese government is a major persecutor of religion.

According to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, for example, China is one of just 17 countries in the world listed as being of “particular concern.”

Let me highlight one area where I think Freedom House could have done better: Protestant Christianity. The Freedom House report focuses on a cross-removal campaign, which ran from 2014-2016 and saw over 1,000 crosses removed from the spires of churches, or the tops of buildings. In addition, a church was demolished.

On the face of it, this is horrific – so many churches shorn of the very symbol of their faith. What better example of a heavy-handed atheistic state persecuting belief?

And yet I think this is not typical of Protestantism in China. I’ve made several trips to the area where the crosses were removed and feel I know the region well.

I’d say that the most important point is that virtually none of these churches have been closed. All continue to have worshipers and services just like before. In addition, the campaign never spread beyond the one province. Some pessimists see it as a precursor for a campaign that might spread nationally, but so far that hasn’t happened and there is no indication it will.

What seems to have happened is a fairly special case. That region is at most 10% Protestant – above the national average of about 5%, but still a minority. But local Christians decided to put huge red crosses on the roofs of buildings and churches, so they dominated the skyline of every city, town, and village across the province. That gave the impression that Christianity was the dominant local religion and irked many non-Christians.

Self-critical Christians told me that their big red crosses were meant well. They were enthused by their faith and wanted to proclaim it. But they also sheepishly said it might also have been a sign of vanity; rather than putting their money into mission work or social engagement, they wanted to boast about their wealth and faith. I felt they were a bit hard on themselves – in a normal, healthy society an open expression of one’s faith should be normal – but it is true that it was also a potential provocation for a state that does not give religion much public space.

In short, this campaign was fairly specific and not representative of most Protestants’ religious experience in China. In his new book China’s Urban Christians, Brent Fulton of the Protestant think tank ChinaSource, writes that political oppression is a secondary concern, even for underground Protestants. Instead he says what keeps pastors of these churches up at night are problems that religious leaders around the world would recognize: materialism and the lures of secular society. The government is a hassle, but is not their main problem.

This mirrors what I’ve seen as well. Protestantism is booming and Chinese cities are full of unregistered (also called “underground” or “house”) churches. These are known to the government but still allowed to function. They attract some of the best-educated and successful people in China. And they are socially engaged, with outreach programs to the homeless, orphanages, and even families of political prisoners. To me, this is an amazing story and far outweighs the cross-removal campaign, which basically ended and seems to have had no lasting consequences.

Dark future?

Now, it’s true that all this could change. Last autumn, the government issued new regulations on religion. The most important point of the rules was to reemphasize a ban on religious groups’ ties to foreign groups – for example, sending people abroad to seminaries, or inviting foreigners to teach or train in China. This is clearly part of a broader trend in China that we see in other areas. Non-governmental organizations are also under pressure, and the surest way to get unwanted government attention is to have links abroad.

Given the predilections of the Xi administration, these new religious regulations could be harshly enforced. We could see unregistered churches forced to join government churches. And we could see outreach programs closed down.

If this happens, then I would say that Protestantism would be suffering from a “high” degree of persecution. And if it happens we’ll need hard-hitting reports condemning it in no uncertain terms. But until this crackdown really occurs, we might be missing the forest for the trees.

Ian Johnson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent based in Beijing. His new book, “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao,” will be published in April. The views expressed above are solely his own.