Story highlights

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 had four beacons, or emergency locator transmitters

One was designed to activate on impact, but satellites did not receive a distress signal

The lack of a distress signal boosts hopes of passengers' families

It is one of the most enduring mysteries of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, and for the families, it’s a reason for hope.

Why didn’t Flight 370’s emergency beacon work?

Why didn’t the beacon send a distress signal to satellites overhead?

And the clincher: Why, if the beacon is designed to activate on impact, should we believe there was an impact? Could the plane have landed intact? Could the 239 passengers and crew still be alive?

The issue resonates with some family members looking for hope where little exists. Of the 26 questions families recently presented to the Malaysian government, 12 addressed the beacon.

Adding to the mystery: Hijackers or renegade pilots cannot disable some of the emergency beacons, namely, the ones attached to the plane’s airframe. They are powered by batteries and inaccessible to the crew. So by all accounts, the attached beacon on Flight 370 should have activated if the plane crashed.

But experts consulted by CNN say there are numerous reasons why a beacon could fail in an ocean crash.

The beacon itself could be damaged by the impact, or its antenna could be sheared from the fuselage, rendering it inoperable.

And there’s one other possibility considered even more likely by some: The crash impact may have actually activated the beacon, but the damaged plane sank in less than 50 seconds, the time necessary for it to transmit its first emergency signal. The beacons do not work underwater.

On Friday, 49 days after Flight 370 disappeared, no one can say with certainty what happened with the plane’s beacons.

That has left some family members with a faint glimmer of hope, but others believing that the beacon system just failed.

What are beacons?

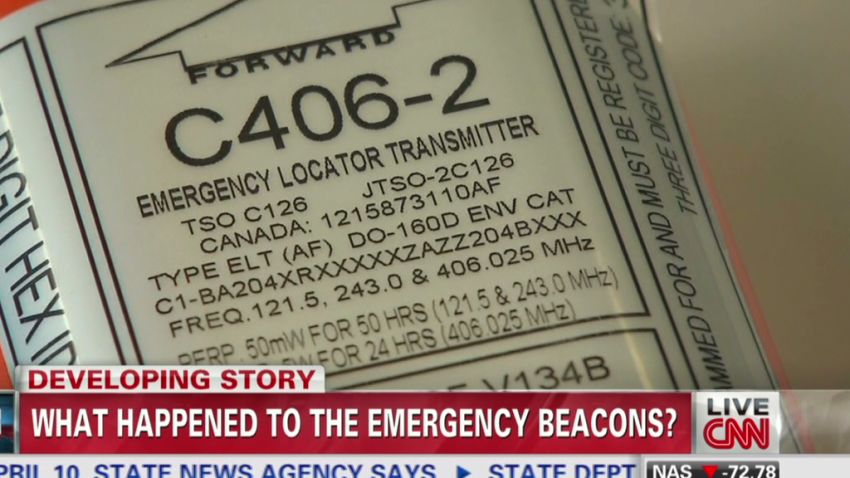

Beacons – more formally called emergency locator transmitters, or ELTs – are devices that transmit an electronic distress signal in the event of a crash.

Unlike the so-called “pingers,” which help investigators zero in on a plane’s black boxes, ELTs are intended to help rescuers locate the plane itself. And, unlike the pingers, they do not operate when submerged under water, owing to the natural laws that govern radio waves.

Malaysia Flight 370 had four of them, Malaysian officials told CNN.

Two of the ELTs were stored with the airplane’s life raft, to be activated by hand or by contact with the water, if the life boats were deployed.

The third ELT was stowed in the cabin.

But the ELT of greatest interest is the remaining “fixed” ELT, mounted to the aircraft frame. The fixed ELT – a Honeywell RESCU 406 AFN – was positioned near the rear door and connected to an antenna on top of the aircraft. It could be activated, either manually by a pilot in the cockpit, or automatically upon impact, by an inertial “G-switch.”

The RESCU 406 AFN was designed “to provide emergency transmission for aircraft flying over land,” according to Honeywell’s published specifications.

“They are not mandated or designed to work under water,” a Honeywell spokesman told CNN.

But experts say any impact – whether on land or at sea – likely would have activated the transmitter.

Once activated, the device simultaneously transmits “bursts” – short, digitally coded signals – on three frequencies. Two of the frequencies – 243 MHz and 121.5 MHz – are VHF frequencies and can help search planes hone in on a target. The third frequency is 406 MHz.

That’s where satellites come in.

Help from above

In 1979, the United States, Canada, France and the former Soviet Union teamed up to provide a global, satellite-based system to detect emergency beacons activated by planes, ships and backcountry hikers and to distribute those alerts to rescuers.

Known as the International Cospas-Sarsat Programme, the enterprise claimed it made its first rescue in September 1982, saving three people involved in the crash of a light aircraft in Canada.

“Cospas-Sarsat has done an enormous amount of good in the world, but almost nobody has ever heard of us,” said Steven Lett, an American diplomat and head of the Cospas-Sarsat Secretariat in Montreal.

Cospas-Sarsat relies on six low-altitude, Earth-orbiting satellites and six high-altitude geostationary satellites, each with advantages and disadvantages.

The six low-altitude satellites, whose main function is to provide meteorological information, orbit the poles and give complete but non-continuous coverage of the Earth’s surface. Because they can only view a portion of the Earth at any given time, the satellite may need to store geographic information from an emergency beacon and rebroadcast it when it comes within view of a ground facility.

The six geostationary satellites, parked in spots more than 22,000 miles above the equator, cover most of the Earth’s surface but cannot determine the location of the beacon unless the location is encoded in the signal.

All of the satellites listen for a beacon’s 406 MHz signals and together can identify a beacon’s location to within approximately 3 kilometers, or just under 2 miles.

If Flight 370’s ELT had transmitted a 406 MHz signal, it “almost certainly would have been picked up by one of the geostationary satellites,” Lett said. Two satellites, India’s Insat-3A and Russia’s Electro-L1, are both parked over the Indian Ocean. It perhaps would have also been picked up by an orbiting low-altitude satellite.

Australia, Singapore, Indonesia and China all have antennas that monitor the satellites’ emergency transmitter. Some or all of them likely would have received the distress call.

But authorities say no satellite signals were sent. No rescue was launched.

Other rescues

Cospas-Sarsat said about five people are rescued every day with the assistance of the satellite system.

But the disappearance of large commercial jetliners is very rare, and consequently, so is the discovery of them.

Cospas-Sarsat said it was instrumental in finding a Varig Airlines B-737 that wandered off course and crashed in the Brazilian jungle in September 1989. And when a Turkish Airlines B-737 dropped off radar near Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands in 2009, an ELT alert was the first confirmation to controllers that the aircraft had crashed.

The organization also said it was the primary or sole source of location information in about 25 other cases involving aircraft with 10 or more passengers.

Somewhere in the Indian Ocean

What can explain the lack of a signal in the Flight 370 case?

Assuming that the device was working correctly, the crash could have broken the antenna or cut the connection with the ELT, rendering it useless.

Another possibility, experts say, is that the aircraft could have sunk before the ELT began transmitting. It takes 50 seconds for the ELT to establish the necessary connection. It only takes one half-second data “burst” to indicate there is an emergency. But it can take a half-dozen bursts – at the rate of one every 50 seconds – to provide information that will allow Cospas-Sarsat to triangulate the beacon’s position.

“In this case, there wasn’t even one burst, according to the reports that we received,” Lett said.

If the plane crashed in the southern Indian Ocean, as Malaysia Airline officials believe, the lack of a distress call could indicate that the plane plunged into the water, or sank quickly, because once underwater, the beacon is ineffective.

Likewise, the water-triggered ELTs in the life rafts would be ineffective if they became submerged, according to published Honeywell manuals for the devices.

Cospas-Sarsat also notes that beacons must have a relatively unobstructed view of the sky to work properly.

“A submerged beacon, or one with its antenna blocked by the body of an aircraft or vessel, is unlikely to be received by the satellites,” the organization said.

Said Honeywell Aerospace spokesman Steven Brecken: “Until the recorders are recovered, we don’t want to speculate what could or could not have happened. We ask the same thing you do, why didn’t the ELT operate? We don’t have the answer.”

Family questions

In a recent letter to Malaysian authorities, a family group showered them with questions about the ELTs.

How many ELTs are on the plane, they asked, adding that they had gotten conflicting numbers.

Did Malaysia Airlines conduct maintenance checks? When was the latest check for MH370’s ELT?

They asked to see the results of those checks.

Was the 406 MHz beacon certified? Was it possible to break the ELT in a crash? Where exactly was it located?

Would the ELT signal be weakened if it was surrounded by metal? Was the cable and blade antenna 9G certified? How much impact is needed to activate the ELT? Had the crew been trained in the use of ELTs? Can a beacon unlock “and bounce [float] to the surface of the water?”

Many of the questions remain unanswered.

But Cospas-Sarsat officials said that previous accidents have exposed shortcomings with the system and that they are working to improve it.

Among other things, they are testing a new constellation of mid-altitude satellites that can better determine the location of an ELT.

And government and industry officials are working on a new generation of ELTs that can monitor a plane conditions, identify problems and send a distress signal before the plane ever reaches the ground.

Or the sea.