Story highlights

Falls are the second leading cause of death by injury, after car accidents

Nearly three times as many people die in the US after falling as are murdered by firearms

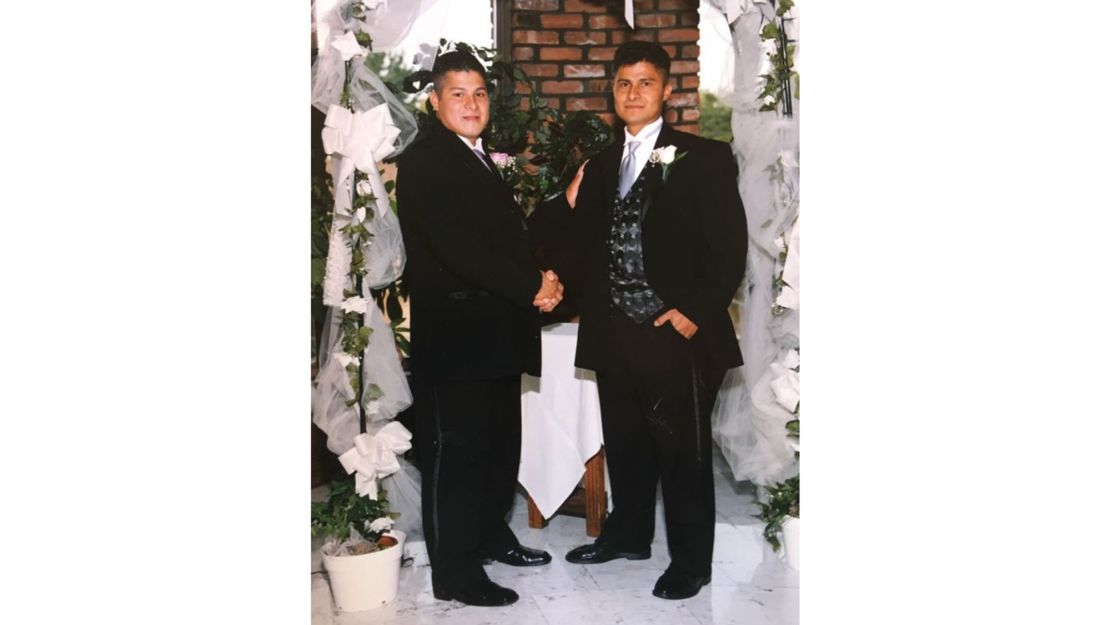

Alcides Moreno and his brother Edgar were window washers in New York City. The two Ecuadorian immigrants worked for City Wide Window Cleaning, suspended high above the congested streets, dragging wet squeegees across the acres of glass that make up the skyline of Manhattan.

On 7 December 2007, the brothers took an elevator to the roof of Solow Tower, a 47-storey apartment building on the Upper East Side. They stepped onto the 16-foot-long, three-foot-wide aluminium scaffolding designed to slowly lower them down the black glass of the building.

But the anchors holding the 1250-pound platform instead gave way, plunging it and them 472 feet to the alley below. The fall lasted six seconds.

Edgar, at 30 the younger brother, tumbled off the scaffolding, hit the top of a wooden fence and was killed instantly. Part of his body was later discovered under the tangle of crushed aluminum in the alley next to the building.

But rescuers found Alcides alive, sitting up amid the wreckage, breathing and conscious when paramedics performed a “scoop and run” – a tactic used when a hospital is near and injuries so severe that any field treatment isn’t worth the time required to do it.

Moreno was rushed to New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, four blocks away.

A forgotten danger

Falls are one of life’s great overlooked perils. We fear terror attacks, shark bites, Ebola outbreaks and other minutely remote dangers, yet over 420,000 people die worldwide each year after falling.

Falls are the second leading cause of death by injury, after car accidents. In the United States, falls cause 32,000 fatalities a year (more than four times the number caused by drowning or fires combined). Nearly three times as many people die in the US after falling as are murdered by firearms.

Falls are even more significant as a cause of injury. More patients go to emergency rooms in the US after falling than from any other form of mishap, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly triple the number injured by car accidents.

The cost is enormous.

As well as taking up more than a third of ER budgets, fall-related injuries often lead to expensive personal injury claims. In one case in an Irish supermarket, a woman was awarded 1.4 million euros compensation when she slipped on grapes inside the store.

It makes sense that falls dwarf most other hazards. To be shot or get in a car accident, you first need to be in the vicinity of a gun or a car. But falls can happen anywhere at any time to anyone.

Spectacular falls from great heights outdoors like the plunge of the Moreno brothers are extremely rare. The most dangerous spots for falls are not rooftops or cliffs, but the low-level, interior settings of everyday life: shower stalls, supermarket aisles and stairways.

Despite illusions otherwise, we have become an overwhelmingly indoor species: Americans spend less than 7% of the day outside but 87% inside buildings (the other 6% is spent sitting in cars and other vehicles).

Any fall, even a tumble out of bed, can change life profoundly, taking someone from robust health to grave disability in less than one second.

Falling can cause bone fractures and, occasionally, injuries to internal organs, the brain and spinal cord. “Anybody can fall,” says Elliot J Roth, medical director of the patient recovery unit at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in Chicago. “And most of the traumatic brain injury patients and spinal cord injury patients we see had no previous disability.”

Scientists are now encouraging people to learn how to fall to minimize injury – to view falling not so much as an unexpected hazard to be avoided as an inevitability to be prepared for.

How we fall

You can trip or slip when walking, but someone standing stock still can fall too – because of a loss of consciousness, vertigo or, as the Moreno brothers remind us, something supposedly solid giving way.

However it happens, gravity takes hold and a brief, violent drama begins. And like any drama, every fall has a beginning, middle and end.

“We can think of falls as having three stages: initiation, descent and impact,” says Stephen Robinovitch, a professor in the School of Engineering Science and the Department of Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada.

“Most research in the area of falls relates to ‘balance maintenance’ – how we perform activities such as standing, walking and transferring without losing balance,” he said.

By “transferring”, he means changing from one state to another: from walking to stopping, from lying in a bed to standing, or from standing to sitting in a chair. “We have found that falls among older adults in long-term care are just as likely to occur during standing and transferring as during walking,” says Robinovitch, who installed cameras in a pair of Canadian nursing homes and closely analyzed 227 falls over three years.

Only 3% were due to slips and 21% due to trips, compared to 41% caused by incorrect weigh shifting – excessive sway during standing, or missteps during walking. For instance, an elderly woman with a walker turns her upper body and it moves forward while her feet remain planted. She topples over, due to “freezing”, a common symptom of Parkinson’s, experienced regularly by about half of those with the disease.

In general, elderly people are particularly prone to falls because they are more likely to have illnesses that affect their cognition, coordination, agility and strength.

“Almost anything that goes wrong with your brain or your muscles or joints is going to affect your balance,” says Fay Horak, professor of neurology at Oregon Health & Science University.

Fall injuries are the leading cause of death in people over 60, says Horak.

Every year, about 30% of those 65 and older living in senior residences have a fall, and when they get older than 80, that number rises to 50%. A third of those falls lead to injury, according to the CDC, with 5% resulting in serious injury.

It gets expensive. In 2012, the average hospitalization cost after a fall was $34,000.

How you prepare for the possibility of falling – what you do when falling, what you hit after falling – all determine whether and how severely you are hurt. And what condition you are in is key.

A Yale School of Medicine study of 754 over-70s, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2013, found that the more serious a disability you have beforehand, the more likely you will be severely hurt by a fall.

Even what you eat is a factor: a study of 6,000 elderly French people in 2015 found a connection between poor nutrition, falling and being hurt in falls.

Training to stay upright

Christine Bowers is 18. She hails from upstate New York, and is a student at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. One day she hopes to teach English abroad.

In January 2016 she had a cavernous malformation – a tangle of blood vessels deep within her brain – removed.

“It paralysed my left side,” she says, as her physical therapist straps her into a complex harness in a large room filled with equipment at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. “I’m working on preventing a fall.”

Under the supervision of Ashley Bobick, the therapist, Bowers is walking on the KineAssist MX, a computerized treadmill with a robotic arm and harness device at the back. The metal arm allows patients freedom of motion but catches them if they fall. Bowers has fallen several times, and those falls made her very skittish about walking, a serious problem in the rehabilitation of those who have fallen. “It’s huge,” says Bobick. “Fear of falling puts you at risk for falling.”

“We’ve been doing what’s called ‘pertubation training’, where I pick a change in the treadmill speed,” says Bobick. “She’s walking along, I hit the button, and the treadmill speeds up on her and she has to react… Her biggest fear was slipping on ice, so I said, ‘You know what? I have a really great way for us to train that.’”

The treadmill hums while Bobick speeds it up and slows it down, and Bowers, her right hand clasping her paralyzed left, struggles to maintain her balance.

“You’re getting better at this,” says Bobick. “You’re getting way better.”

The KineAssist is an example of how technology once used to study ailments is now used to help patients. Advanced brain scanning, having identified the regions responsible for balance, now diagnoses damage that affects them.

Accelerometers attached to people’s ankles and wrists have been used in experiments, plotting induced falls directly into a computer for study, and are now being used to diagnose balance problems – or to detect when someone living alone has fallen and summon help.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology took the “wearable” out of the equation by developing a radio wave system that detects when someone has fallen and automatically summons help. The Emerald system was shown off at the White House in 2015 but is still finding its way to a market chock-full of devices that detect falls, invariably pendants.

Not that a device needs to be high-tech to mitigate falls. Wrestlers use mats because they expect to fall; American football running backs wear pads. Given that a person over 70 is three times as likely to fall as someone younger, why don’t elderly people generally use either?

The potential benefit of cushioning is certainly there.

The CDC estimates that $31 billion a year is spent on medical care for over-65s injured in falls – $10 billion for hip fractures alone (90% of which are due to falls). Studies show that such pads reduce the harmful effects of falling.

But older people have all the vanity, inhibition, forgetfulness, wishful thinking and lack of caution that younger people have, and won’t wear pads.

Padded floors would seem ideal, since they require none of the diligence of body pads or canes. But padding environments is both expensive and a technical challenge.

There are materials designed to reduce injuries from falls. Kradal is a thin honeycombed flooring from New Zealand that transmits the energy of a fall away from whatever strikes it, reducing the force.

A study of the flooring in Swedish nursing homes found that while it did reduce the number of injuries when residents fell on it, they fell more frequently when walking on it, leading to a dilemma: the flooring might be causing some falls even as it reduced the severity of resulting injuries.

One unexpected piece of anti-fall technology is the hearing aid. While the inner ear’s vestibular system is maintaining balance, sound itself also seems to have a role.

“We definitely found that individuals with hearing loss had more difficulty with balance and gait, and showed significant improvement when they had a hearing aid,” says Linda Thibodeau, a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas’s Advanced Hearing Research Center, summarizing a recent pilot study. “Most people don’t know about this.”

Alcides’ recovery

After Alcides Moreno arrived in hospital after his fall, doctors at New York-Presbyterian did not want to risk moving from the emergency room into a surgical theater for fear that the slightest additional bump might kill him. They started surgery in the ER.

He had two broken legs, a broken arm, a broken foot, several broken ribs, and a crushed vertebra that could have paralyzed him, as well as two collapsed lungs, a swollen brain, plus several other ruptured organs. Alcides was given 24 pints of blood and 19 pints of plasma before the bleeding could be stopped.

Doctors marveled that he was alive at all, reaching for an explanation not often used in medical literature: “miracle”.

He underwent 15 more surgeries and was in a coma for weeks. He was visited by his three children: Michael, 14, Moriah, 8, and Andrew, 6. His wife, Rosario, stayed at his bedside, talking to him. She repeatedly took his hand and guided it to stroke her face and hair, hoping that the touch of her skin would help bring him around.

Join the conversation

Then, on Christmas Day, Alcides reached out and stroked not his wife’s face but the face of one of his nurses.

“You’re not supposed to do that,” Rosario chided him. “I’m your wife. You touch your wife.”

“What did I do?” he asked. It was the first time he had spoken since the accident, 18 days earlier.

His doctors predicted he might walk again, after lengthy rehabilitation, though the challenges proved to be not only physical but also mental. People who fall suffer the expected physical injuries, but accidental falling also carries a heavy psychological burden that can make recovery more difficult and can, counter-intuitively, set the stage for future falls.

Alcides Moreno is unable to return to work but received a multimillion-dollar settlement in his lawsuit against the scaffolding company, Tractel, after a Manhattan court found that it had installed the platform negligently. The sum wasn’t revealed, but a source said it was more than the $2.5 million that Edgar’s family received.

This is an edited extract from an article first published by Wellcome on Mosaic. It is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Copyright 2015 The Wellcome Trust. Some rights reserved.