Editor’s Note: David M. Drucker is a senior political correspondent for the Washington Examiner and a CNN political analyst. The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

The 1970s and 1980s, the formative years of my upbringing in suburban Los Angeles, were a golden age for the network television situation comedy.

In sitcom world, family disputes–by which I mean kids behaving badly,–were rationally discussed and lovingly resolved, as if the fathers were trained child shrinks. I’m looking at you, Mr. Keaton.

It wasn’t like that in my house.

My father, a first generation American, born in 1933 in Chicago and who later served in the US Army during the Korean War, yelled.

He yelled a lot.

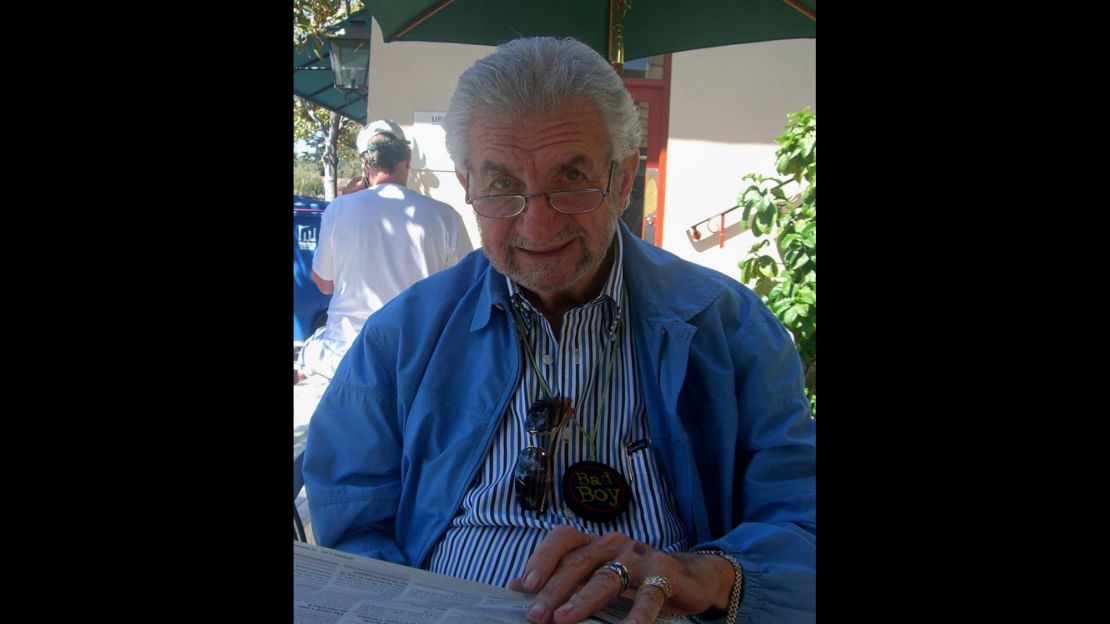

Ron Drucker was a passionate, emotional man. Even when he didn’t yell, his booming baritone voice spoke with such definitive authority that he might as well have been yelling, as far as I was concerned.

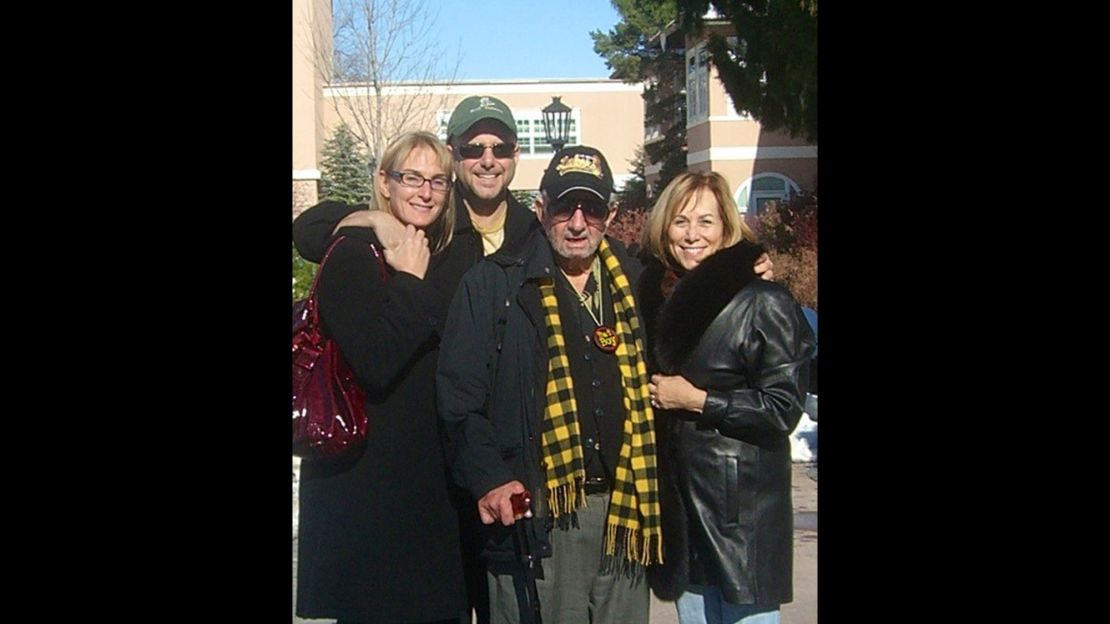

He wasn’t the easiest man to live with, to say the least. I didn’t agree with everything he did. I didn’t like everything he did, and our relationship could be contentious. As I grew into adulthood, that meant that when he yelled, I yelled right back.

But my father lived his life with integrity.

He taught me how to stand on my own two feet, taught me what self-respect was, taught me to never ever quit. He taught me how to love a woman and how to care for a family. He taught me how to be a father by loving me enough to not care whether I liked him, because he knew he was raising me to be a man.

Ron Drucker was the son of two poor Jewish immigrants – one, my grandmother, who fled the pogroms of Poland, the other, my grandfather (and namesake), who came to America from Montreal.

When my father was 13 months old, they traveled two days by train to Los Angeles, where they settled, raising my father in the poor, rough-and-tumble neighborhood of Boyle Heights, an enclave of working class Jews and later Hispanics, east of downtown.

My grandparents loved my father. They clothed him and fed him.

But they did not have the capacity to show him affection, to nurture him and tell him how much they loved him. In this way, my father was self-taught, because in our house there was more than just yelling, as would become apparent to me later on.

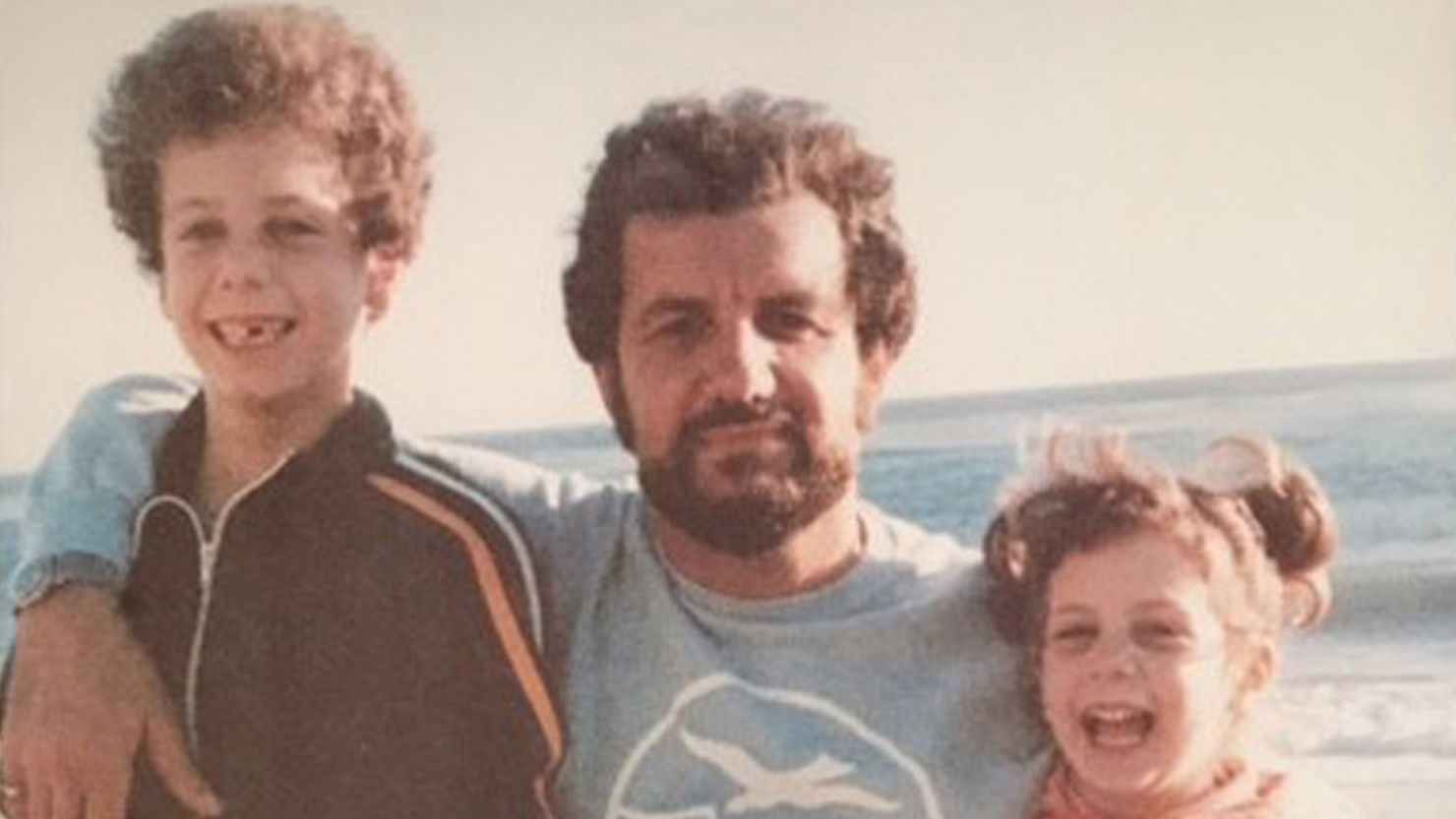

My father married my mother, Sari, in 1970 at the age of 36 (she was 20). I was born one year later; my sister, Pamela, came along four years after that. He was older than most first-time husbands and fathers of that era.

Over the next two decades, as divorce and split families grew in acceptance and frequency, my sister and I were raised in an intact house full of love.

Our father told us that he loved us every single day, flooding us with the kind of attention I suspect he wanted but didn’t receive from his own parents.

Of course, what sounded like love to him could sound like a broken record of virulent criticism to me: You’re not working hard enough. You’re not trying hard enough. You’re not studying hard enough. What the hell’s wrong with you? (That last one is my favorite).

My father came from nothing. He dreamed of the life he wanted, and he worked incredibly hard to achieve it.

For him, that meant a nice home on the beach in Malibu, season tickets to UCLA basketball and football games, and plenty of cash in his pocket. He used credit cards, but the old man wouldn’t leave the house without a wad of $100 bills befitting a mobster.

My father made a lot of money in the home furnishings industry.

He was an innovative sales and marketing executive, entrepreneurial and self-employed for much of my life. Most of the time, he simply referred to himself as a “salesman.”

The consummate businessman, he worried I was taking a vow of poverty by choosing to write for a living, and would’ve been proud that I was using a story about him to make a couple of bucks.

Amid the success my father enjoyed, there was failure. But he persevered.

I remember years ago that my father was trying to chart a path back to prosperity after the collapse of a business he owned and ran with my mother, and the personal financial implosion that accompanied it.

He told me about a job offer. It would have paid reasonably well, it would have been secure and it was something he could have done in his sleep. He was in his late 50s and had a family to think about, and he needed money. He turned it down.

My father had a vision, and that wasn’t the life he wanted to lead. He simply wouldn’t give up on his dream. My dad once told me that he never judged his life by who was on the rung of the ladder below him, but who was on the rung above him.

That’s how he lived.

All the while, he was teaching me how to be a man, a husband, a father.

Sometimes I wonder if we really understood each other.

I started out wanting to be him. These days, some people like to point to my clothes or my beard, all of the superficial things that might remind family and friends of him. And I do take pleasure in that.

But I strive to emulate the essence of the man: A true American success story who excelled in his chosen profession and who raised a family with all the love one man could muster.

He passed away in March 2013 after a battle with Alzheimer’s. This will be my fifth Father’s Day as a dad, and my fourth without mine. I loved my father and will miss him dearly for as long as I live.