Story highlights

The Trump administration rolled back an Obama-era attempt to curtail private prisons

The private prison industry saw stock prices soar for months after the 2016 election

The private prison industry – one of the most controversial pieces of the US carceral state – has essentially recovered a year after the Obama administration sent a chill down its spine.

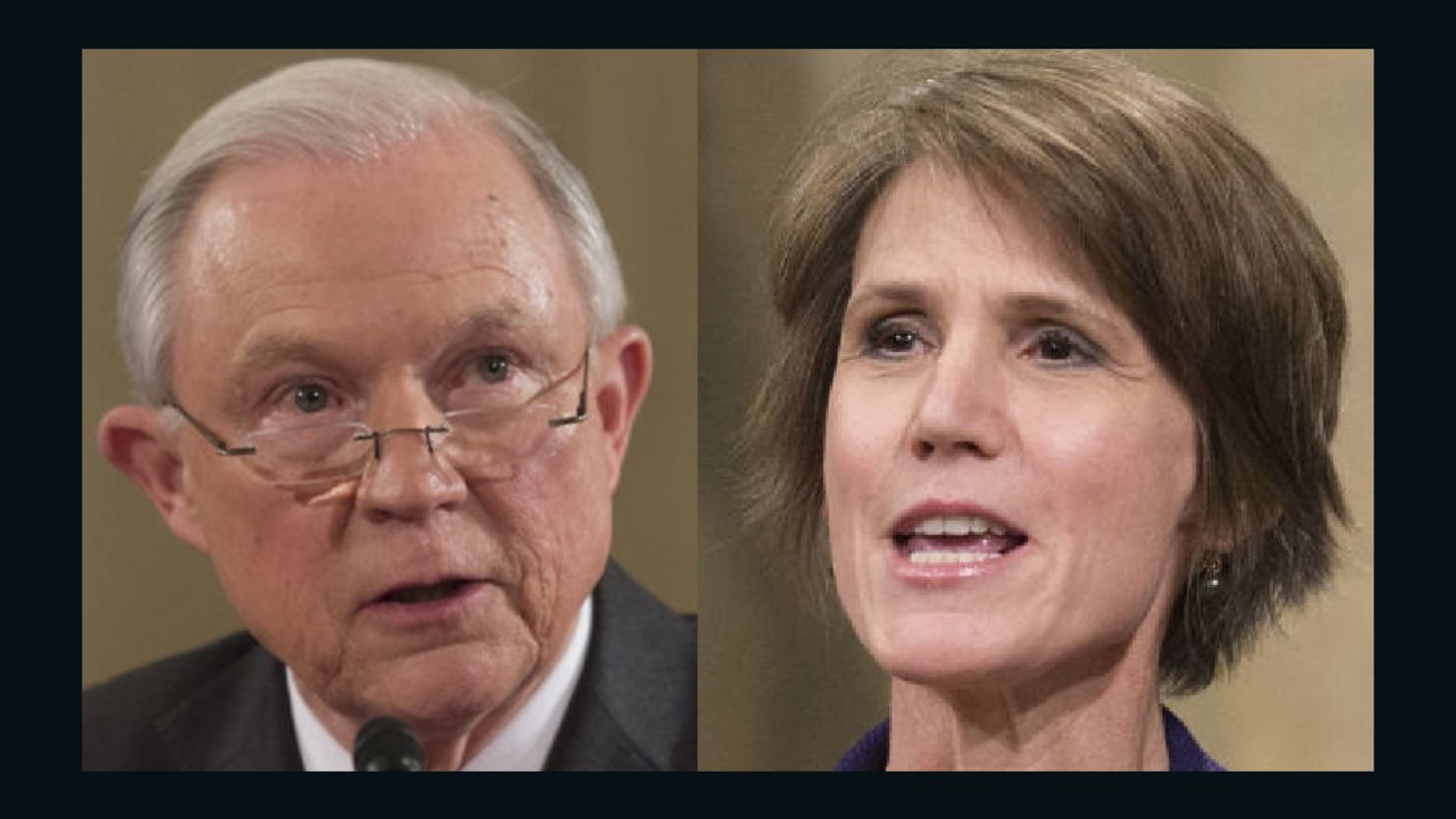

Last August, then-Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates issued a memo calling on the Department of Justice to begin curtailing its use of private prisons – incarceration run by for-profit companies.

Stocks for one of the two major publicly traded prison companies nosedived, and with a presidential victory for Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton widely expected, the Yates memo seemed to indicate the heyday for the private prison industry had passed.

But the impact of the decision was not lasting.

On November 8, Trump won the presidency, and just days into the job, Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded Yates’ guidance.

The private prison industry saw stock prices soar for months after the election even relative to the already robust stock market.

And one year ago Friday, from that now-rescinded memo, the situation for these prisons looks largely like what it was before the Obama-era Justice Department sought to change the status quo.

The controversy

Critics of private prisons contend they are inefficient and inhumane.

When she issued her memo, Yates cited a government watchdog report that said private prisons were generally more expensive and offered worse results. Groups such as the ACLU lauded the report and Yates’ decision while the private prison industry reeled. It called the report imbalanced and challenged its comparison of private and public facilities.

Alexander “Sasha” Volokh, an Emory University law professor and supporter of private prisons, told CNN the report was faulty.

“It’s hard to do a good study that really compares them well,” Volokh said, citing the differences in prison populations and lack of reliable performance measures.

The other major strain of criticism comes from the profit motive, the argument that a for-profit carceral facility will necessarily seek to cut corners and increase the number of people behind bars.

Volokh said issues with performance in private prisons could be corrected with stronger contracts and that the government could use the profit motive to its advantage by making companies compete for results. He also pointed out political efforts by labor unions for public-sector prison guards, arguing those had a much stronger impact on mass incarceration than for-profit companies.

Critics have contended otherwise, pointing to overcrowding among many other reported abuses and political efforts by the companies to back tough-on-crime candidates.

“Profit should not play a role in the criminal justice system,” said Udi Ofer, deputy national political director for the ACLU.

Ofer also said profit found its way into other corners of the criminal justice system besides prison privatization, like the multibillion-dollar bail industry, which has in some places found bipartisan opposition.

Meanwhile, Sessions, in his memo rolling back the Obama-era policy, said curtailing the use of private prisons “impaired the bureau’s ability to meet the future needs of the federal correctional system.”

Following years of relatively low crime rates and the more recent dip in the prison population, Sessions has pushed for a crackdown on drug and gun offenses and offered a wholesale endorsement of Trump’s “law-and-order” campaign.

The companies

When it comes to private prisons in the US, the two biggest names are CoreCivic – the new name for the Corrections Corporation of America – and GEO Group. Management & Training Corporation, another company with prison operations, is not publicly traded.

While CoreCivic and GEO Group have, for the time being, seen a halt to their massive surges since the election, both in their second quarter earnings calls said they expected more federal contracts as the departments of Justice and Homeland Security detain more people.

Both companies welcomed the Trump era with large donations.

In January, GEO Group’s Pablo Paez, the company’s vice president of corporate relations, told USA Today it donated $250,000 to Trump’s inaugural committee. OpenSecrets’ list of inauguration donors noted the GEO Group donation, as well as CoreCivic’s $250,000 contribution.

The month before the election, GEO Group hired two former Sessions aides as lobbyists: David Stewart and Ryan Robichaux, according to Politico.

The Bureau of Prisons renewed two large contracts for GEO Group in May, and CoreCivic said in its second quarter earnings call it expected the Trump administration would mean more contracts for the company.

Private prisons and immigration

Private prison companies overall make up a small share of the incarceration pie, both on the federal and state levels, Justice Department data show. This means while private prisons are significant, they don’t account for most of mass incarceration facilities.

A large share of people locked up in federal private facilities are criminal undocumented immigrants, and populations at the local level vary wildly depending on the state. Many states have no private institutions while others contract with these companies for a sizable share of their prisoners.

So when it comes to the Trump administration, these prison contractors are eyeing both criminal law enforcement and immigration. But on both counts, the people going to private prisons paid for by the federal government are largely immigrants.

From Day One of Trump’s campaign, he pushed heavily for a crackdown on undocumented immigration, and once in office, Trump ordered Immigration and Customs Enforcement to ramp up its enforcement efforts.

For years, ICE has outsourced the bulk of its detention operations to the private sector.

Last year, then-Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson followed the Justice Department’s footsteps by asking his department to look at its own use of private prisons. What resulted was a sweeping assessment of their use and an accounting that showed some 65% of people ICE detained were kept in for-profit facilities.

Despite the standing outcry from civil liberties groups like the ACLU, DHS said its use of private prisons was necessary and voted to continue its existing policies.

ACLU National Prison Project Director David Fathi argued that both the DHS report and Yates’ now-rescinded memo were tempered wins for the opponents of private prisons. DHS’ vote, he noted, was not unanimous and came with a dissent. And Yates’ memo at least showed the ability of a Justice Department – albeit one with different ideological leadership – to phase out private prisons.

“Once the bell is rung, it can never be unrung,” Fathi said.