How ISIS changed Iraqi schools

Iraq’s education system has been devastated by ISIS, but there’s still hope of avoiding a ‘lost generation’ Photographs by Diego Ibarra Sánchez

Story by Kyle Almond, CNN

Iraq’s education system has been devastated by ISIS, but there’s still hope of avoiding a ‘lost generation’ Photographs by Diego Ibarra Sánchez

Story by Kyle Almond, CNN

After two years in the darkness, living in the shadow of ISIS, children in northern Iraq are finally getting a chance to learn again.

Schools are starting to reopen as Iraqi forces push back the terror group, and more might be opening soon after Iraq claimed victory this week in Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city and ISIS’ last major stronghold in the country.

“But war is not finished with the last bullet or when they are raising the flag,” warns Diego Ibarra Sanchez, a Spanish photographer who has been documenting the country’s educational crisis.

Much work remains to rebuild and restore what has been lost.

Asaf Ahmed, a young Iraqi refugee, dropped out of school when ISIS came to his town in northern Iraq.

Pictures of students lie on the floor of an abandoned school in Hajj Ali, Iraq.

“ISIS, in a couple of years, wiped out years and years of investment,” Ibarra Sanchez said.

His photos show the devastation. Schools abandoned and heavily damaged. Libraries destroyed. Thousands of books and manuscripts burnt.

ISIS used many schools as headquarters for their fighters, but in others they continued to teach young children -- albeit with a much different curriculum.

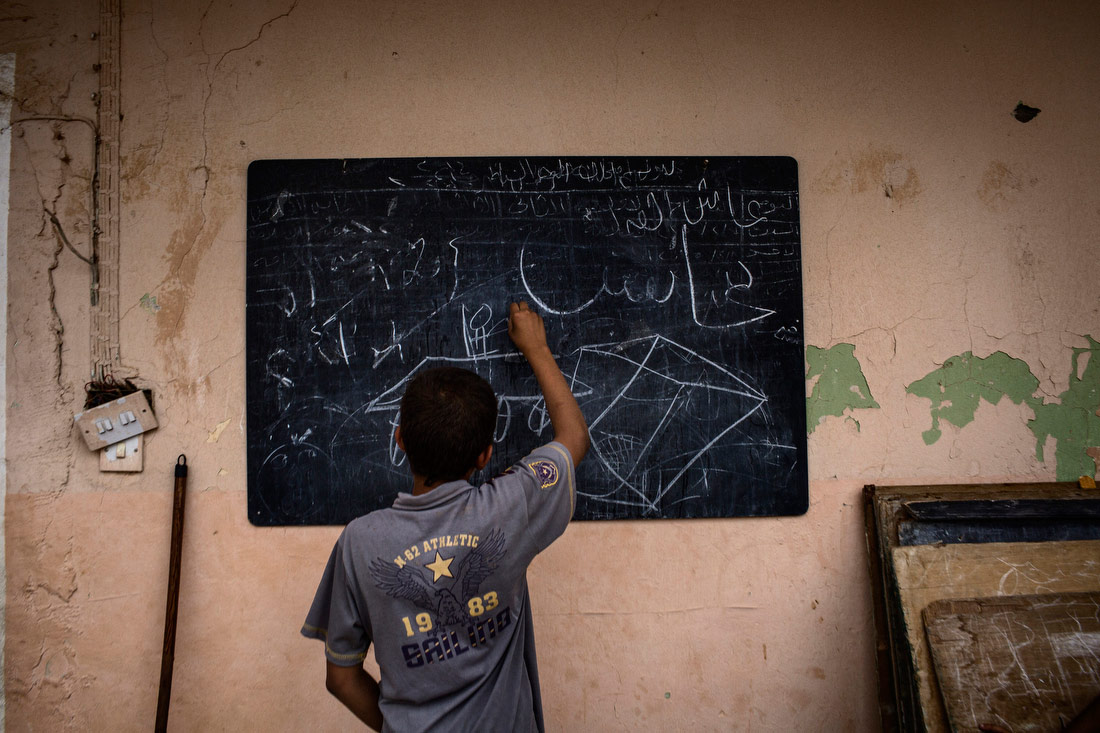

A young refugee draws on a blackboard inside Hajj Ali High School, which was converted into a shelter after ISIS moved into the region.

Damage from an airstrike is seen at an abandoned school in northern Iraq.

Instead of subjects such as history and geography, students were taught religious extremism and violence. A math textbook, for example, asked students in one exercise to calculate the number of “unbelievers” who could be killed by a car bomber. Another referenced how many explosives a factory could produce. All plus signs were removed because they resemble the Christian cross.

“Parents were quite afraid of sending their kids to the (ISIS) schools,” Ibarra Sanchez said. “Sometimes they were forced to.”

A 15-year-old, part of a militia that opposes ISIS, takes a position outside Qayyara, Iraq.

Pictures are defaced outside a school in the Old City of Mosul. ISIS fighters deface anything they deem to be religious or Western idolatry, said photographer Diego Ibarra Sanchez.

And it wasn’t just the children.

“I met one teacher, 51 years old. She was forced to impart the lessons during the regime because ISIS was telling her, ‘If you are not giving the lessons, we are going to kill you,’ ” he said. “So she was forced to go to the school and to teach. Now she's quite happy because she's in east Mosul in a school that is open again.”

UNICEF and other nongovernmental organizations are helping to rebuild schools and make sure children have whatever they need to succeed. Earlier this year, UNICEF estimated that one of every five schools in the country were out of use.

Civilians flee in Mosul as Iraqi forces advance on ISIS in July.

The library of the University of Mosul was destroyed in battle and turned into an ISIS facility.

One big problem, Ibarra Sanchez said, is that many of the buildings are full of booby traps set by ISIS. The schools have to be carefully cleared by specialists before lessons can resume.

Even when schools restart, students still face an uphill climb. Many are now two years behind on their studies, and there’s a lot of ground to make up.

Ibarra Sanchez fears that this could become “a lost generation,” but he was impressed by the children’s resilience and their eagerness to learn.

A young student attends school in east Mosul in April.

A ray of light hits a pile of desks inside an abandoned school in east Mosul.

“They don’t deserve to grow up without a childhood as we understand childhood,” he said. “That right to play, that right to learn, that right to share without being afraid that someone is coming to your house or you cannot go to school.”

Although he has seen many improvements since an August visit last year, more equipment and more teachers are still needed for the schools, Ibarra Sanchez said. And the ISIS threat continues to loom in some areas.

“Life is starting again,” he said, “but there is a long way, a long path after a bloody war.”

Diego Ibarra Sanchez is a Spanish photographer based in Lebanon. He is a co-founding member of the MeMo photo collective. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

Photo editor: Brett Roegiers