Freedom and separation: Memories of the independence generation

Seventy years ago, the Indian subcontinent won independence from the British Empire. The result was the birth of two countries. Hindus and Sikhs left the newly-formed Pakistan and headed for India, while many Muslims made the reverse journey. It was a hard migration, with around one million people estimated to have lost their lives in the exodus. Here are the stories of some of the people who lived through that pivotal moment in South Asia's history.

Nasreen Rehan

Sara Farid/CNN

Nasreen Rehan

“I remember hearing Lord Mountbatten, Jinnah and Nehru on the radio.”

Rehan shares a birthday with both India and Pakistan, turning six on the day of independence. As her parents returned to India to arrange their finances, Rehan was sent to Rawalpindi to be with her grandmother.

“I remember hearing Lord Mountbatten, Jinnah and Nehru on the radio as the new country was announced,” she says. “But there was an air of anxiety in our home, as there had been no word from my parents. Even though I was just a child, I knew something was wrong.”

After four months, Rehan’s parents returned -- just in time for Pakistan’s first Eid. But they had witnessed violent bloodshed on their return to India.

“I remember running to them, my mother crying. My father, who used to be so plump was now thin. They had been stranded in the riots and had been unable to retrieve much (from our home). My mother had seen our Muslim neighbors being shot dead in front of her. Since there was a curfew, the sons on an old lady next door had to bury her in a shallow grave in front of their house.”

But Rehan’s parents were home – and that was the most important thing.

“We were safe, they were safe and this country was safe for us. I was only a child, but I remember that for years after partition, a lot of the beggars in the streets of Rawalpindi were young girls. They’d gone mad, or had been raped and abandoned. They roamed the streets, lost -- no longer Sikh, Muslim or Hindu."

Pervez Khan

Sara Farid/CNN

Pervez Khan

“I can’t explain the passion and the relief.”

Born in the British hill station of Shimla, Khan lived in a refugee camp outside the city as his family waited to relocate to Lahore. His father, a Muslim doctor, helped in the camp using donated medical supplies.

“My father made a tent with white sheets and painted a red cross to indicate that this was the Doctor’s tent,” Khan recalls. “Dysentery and typhoid was widespread. A padre in a church close to the field allowed my father to operate there in secret at night.”

Aged just 7, Khan then fell victim to an attack as he prepared to leave the camp. He recalls the sky lighting up before he was struck by bullets.

“My knees felt hot and I could smell blood. My father was shouting. I was wounded, my mother had been shot in the ribs, my sister had been shot and one of our servant’s feet had been blown off. My father spent the whole night tending to the injured in the church.

“I had three bullets lodged in my legs, but my father put me on the train and told me not to be scared. While peeking out of the window, I saw dead bodies. They were like cartoons with vultures eating them. And then suddenly we were in Pakistan. People screamed with joy -- the passion, I can’t explain the passion and the relief. We yelled ‘Pakistan zindabad’ (long live Pakistan) as people brought candy to the train.”

Anwar Kemal

Sara Farid/CNN

Anwar Kemal

“I didn’t realize what a momentous thing was happening.”

Kemal was born before partition in 1943 in the city of Bhopal and arrived in Pakistan in October 1947.

“We took a chartered flight out of Bhopal, we left everything, we only had a change of clothes and I was very young. I remember a green football that I had been allowed to bring back with me, it was the only toy from my old home. We were part of the royal family of Bhopal. I don’t have many memories of the flight. I didn’t realize what a momentous thing was happening, in commercial flights we would get served omelets and on this flight, we got nothing, I was very upset about that.

After the trip, everything changed, including his family situation, with his parents separating.

“If they (my parents) had stayed back in India, my mother would not have been as free from society’s constraints. Pakistan was a new land of opportunity and she was a very strong beautiful woman. She had a modern outlook for our future and us in this new country.”

Kemal continues to believe in the great possibility of Pakistan and the opportunities life there affords.

“There was deep concern and hardship but opportunities arose. I’ve spent my life serving this country and I’m still very proud to have done so “

Amanullah Khan

Sara Farid/CNN

Amanullah Khan

“It’s high time that we learn to live together as better neighbors.”

Khan, who was born in December 1939, was just a child when he was forced to flee his family’s village in the mountainous region of Jammu in Kashmir to escape the outbreak of violence.

“The villages around us were being set on fire and every day we would get news of something horrible that had been done by the Hindu extremists. My older brother was already in Lahore, and we got news that convoys were deporting from Jammu to Sialkot, just across the new border.

The convoys were only taking women and children and the men and the elderly were left behind. It was a cold day, and I remember sitting in the back of the truck with my mother holding me and passing a canal. There were Hindu extremists hiding in the bushes, suddenly I could hear bullets and they came with knives, I clung to my mother and she was pulled out and I fell out with her.

I remember them coming to get me, she covered me and they hit her instead, her forehead was bleeding, a gash had been opened. I was clinging to her and she kept saying run Amman, run but I couldn’t leave her, I was covered in her blood, it was very, very, very cold, there was blood and people dying all around me.

I didn’t want to leave her; I was refusing to leave her when suddenly a lady dragged me into the canal to take me to safety and to the other side, I remember seeing her lose consciousness.”

Khan lost 17 members of his family that day, including sisters, cousins, and most tragically of all, his mother.

“We didn’t have a body of hers to bury. I have no photograph of her, just memories, the breakfast she used to make me, the smell of chai, sometimes she comes in my dreams. Her name was Begum Jaan.”

Khan spent the next 17 days in a refugee camp until his father found him. The two of them then crossed the border into Pakistan to meet Khan’s older brother in Lahore.

“I will never forget that nightmare, I can never forget the details of that day. Every sixth of November my brother would ask me to narrate what happened and I would for that was his way of remembering her. It was hard in the new country and we were not rich but we worked hard and my older brother made sure I went to the best schools.”

Despite what Khan was forced to endure, he sees no reason to be bitter.

“I have no hate in me, who would I hate, who could I blame? I don’t blame India for the loss of my mother, it’s just the atmosphere that existed at that time. It’s high time that we learn to live together as better neighbors.”

Riffat Shaukhat

Sara Farid/CNN

Riffat Shaukhat

“My aunt walked over the border with her baby in her arms.”

Shaukhat, who was born in 1940, remembers only fragments of her family’s journey by train from Jullundur in India to Pakistan.

“I can still see the porcelain, I can still see the bay windows and the cushions, the colorful glass windows, the way the light streamed through.”

Shaukhat’s father worked for the railways and was tasked with the responsibility of bringing people safely from India to the new Pakistan. Because of his job, her father had a bounty placed on his head by Indian extremists. Yet, despite the dangers faced by Shaukhat’s family, she maintains that they were among the lucky ones.

“My aunt walked over the border with her baby in her arms. There was no water and (when) the rain came, she would squeeze her clothes for water to drip out to give to her baby. Refugees would come to our courtyard with horror stories, we heard a story of a pregnant Muslim woman who was killed, her dead baby ripped from her womb and her killers holding the fetus aloft yelling ‘this is Pakistan!”

Parveen Haq

Sara Farid/CNN

Parveen Haq

“I don’t recognize this city that I grew up in.”

Haq was born in 1923 in Murree, a Pakistani hill station. Her father was in the army and the family had many Hindu neighbors and friends.

“There was a Mrs Kapoor who lived close by and she would take care of me all day. I had a Sikh friend, Kulwandd Kaur, who would learn Urdu because she said it was my language and I was her best friend. The tragedy is that during the riots they went to Dehradun which became India and we could never trace them. The Kapoor family shifted to Delhi and over the years we couldn’t keep in touch.”

Haq, who vividly remembers burning lamps and celebrating Diwali as a child, says life in Pakistan is now very different.

“I don’t recognize this city that I grew up in. Once during the riots my father got a phone call from a police office about a Hindu man who was being persecuted, he was scared for his life so my uncle shut him up in our bathroom to save him and help him escape.”

Anayat Massi

Sara Farid/CNN

Anayat Massi

“This independence was for the Muslims and Hindus... What changed for us (Christians)?”

Massi is 101 years old and lives in the Christian slums of Islamabad, where he worked as a tailor.

“I used to work on the fields of a Hindu landlord, I had Hindu friends, one of them was Viroo, he left with the rest of them. Nobody was happy. I am a Christian, we were told by the Hindus to stay with the Muslims. Before partition I used to get paid in wheat for my labor, we’ve seen good and bad times but this independence was for the Muslims and Hindus... What changed for us? Nothing.”

Abdur Rehman

Sara Farid/CNN

Abdur Rehman

“Our young boys went off to fight in the big world war across the water for the English.”

Rehman was born in 1928 and lives in Colingernath, an old village that is now a part of Islamabad.

“I remember when the English would come here, the Muslims were poorer than the Hindus. Our young boys went off to fight in the big world war across the water for the English. Three of them died, it was a big thing for the village.”

Rehman says his life has not changed much, despite the great geopolitical shifts of the last century.

“The British never made a hospital or pharmacy for us… 70 years later we still don’t have those facilities here. First the Muslims were killed and now look at us. Muslims are killing each other here in this country.”

Malik Mohammad Iqbal

Sara Farid/CNN

Malik Mohammad Iqbal

“We welcomed them (Muslims) and now their children and their children’s children are part of this land.”

Iqbal, who was born in 1931 in the village of Saidpur, has fond memories of pre-partition life.

“We had orchards and orchards of the best fruit here, plums, apricots, oranges, It was so beautiful, The Hindu families had many business, there was a store that sold sweetmeats and another that sold fabric. I remember. They were our neighbors. My sister, Fatima, who is now dead, her best friend was Shanti, a Hindu girl. When Fatima got married, Shanti’s family spent so much money on her wedding and we did the same for Shanti’s wedding. Shanti was strong like an ox, she could lift big sacks of wheat and we would be amazed!”

That sense of harmony was forever lost, says Iqbal, with the news of partition.

“Our Hindu neighbors didn’t want to leave. We didn’t want them to leave but that’s the way of the world, they cried so much, I remember seeing them sitting on the trucks saying ‘we’ll come back. Keep our homes safe. We will come back home.’”

Shanti left with her family and Iqbal would never see those Hindu friends again.

“The Muslims who came from across the border were broken, they were poor, they had seen many horrors, we welcomed them and now their children and their children’s children are part of this land, this village is as much theirs as it is ours.”

Neelam and Devendra Nath Nanda

Omar Khan/CNN

Neelam and Devendra Nath Nanda

“From the newspapers, it was clear there would be two states, one Hindu and one Muslim.”

Devendra Nath Nanda was born in Jalandhar, India and went to high school in Lahore. He was 14 years old at the time of partition.

“From the newspapers, it was clear there would be two states, one Hindu and one Muslim. We made up our mind to go to our grandfather’s place, which was going to be in India. We tried to convince our father, and he said, “What are you doing? My father, my great grandfather lived here. The rulers were Muslims, and then English, and it was very peaceful, so we will live here peacefully.” When the separation came, he opted for Pakistan. But later he changed it to India because we were asked again just before independence.”

Nanda left Lahore with his mother and siblings on August 13 and made the journey to India by train. His father, a civil servant, decided to stay back to collect his last paycheck. But he ran into trouble when he was ready to leave.

“He was caught in riots. He lived in a refugee camp without his family, without proper clothing and proper food for 21 days.”

Nanda’s father finally made his way to the family in Mussoorie, a hilly town in northern India. They went on to move to Shimla, the former summer capital of British India, while Nanda moved to Jalandhar to study engineering.

Like countless others, Nanda and his family forged ahead to rebuild their lives.

Nanda’s wife Neelam, who he married in 1960, has a similar story to tell. Like her father-in-law, her own father was also intent on staying back, but reality dictated otherwise.

“I was eight years old at the time of the partition. My father thought that he would stay on but later said, ‘No, I’ll go.’ On the night of August 27, we left in a convoy.”

While they did witness violence along the way, for Nanda’s wife, the naiveté of childhood shielded them from the trauma.

“Now we know how we came to India but at the time, we were so little. Eight years old. My brother was just a year old. It was not difficult.”

As time moved on, the legacy of partition became but a memory and Nanda is pragmatic about his past.

“I still dream of Pakistan. But I have built this house, I love this house. You can’t stop loving this, start loving this. You can’t do that. That is too far past.”

Sat Pal Rawal

Omar Khan/CNN

Sat Pal Rawal

“The whole train was butchered. That’s what we were told later.”

Born in 1940 in Montgomery district, known today as Sahiwal in Pakistan, Rawal was born into a life of privilege.

Rawal’s father was a wealthy landlord who at one point owned half the town of Okara, where the family of 11 lived. Bathing in milk, going to school in a horse drawn carriage, there was little to worry about for Rawal and his family.

This all changed during the partition.

“Everyone knew it was coming. Those days, trains were flying from Pakistan to India but there was no certainty how many trains would come in a day. I remember there were seven or eight families who were dependent on my father. We all went to the station, we were waiting for the train.”

The train finally arrived in the evening and as the families climbed onboard, his older sister suddenly had a change of heart.

“She came out and told my mom she wasn’t going because her husband was still expected from the village. My mother and sister were on the platform, everyone else was inside. My father then asked everyone to get down. He said we were not going this way.”

His sister’s last minute decision saved the entire family.

“The whole train was butchered. That’s what we were told later.”

It was not unusual for trains to arrive with all passengers maimed to death. These were known as “ghost trains”.

Rawal and his family finally crossed the border in a caravan. It took them three days to reach India.

“The journey was not simple. There were around a 100 bullock carts and only two Gorkhas on horse. At one stage, people felt tired and we decided to rest. People were also feeling thirsty and we walked up to the village pond. It had been divided into half, people would use it for drinking, another portion for washing. What we saw was a buffalo. It had been cut and there was blood oozing. We couldn’t drink the water.”

Once in India, Rawal and his family made their way to a refugee camp in Kurukshetra.

With no money, they had to learn how to survive. Countless shops and houses had been left empty as people fled across the border. Rawal’s father decided to rent a grocery store.

While it helped the family to make ends meet, it was a far cry from their life in Pakistan.

“My father had never worked in his life. My elder brother was 14. This was not what anybody had been exposed to, we had a different life. But you have to live, no?”

Raj Suneja

Omar Khan/CNN

Raj Suneja

“If we had opened the (train) doors, we would’ve been finished.”

“It has been 70 years. My heart is saddened when I start remembering the memories.”

Suneja was 16 when she left her home in Lahore for India.

Life was comfortable for the family of nine. Her father was a well-respected lawyer who had defended the socialist revolutionary Bhagat Singh.

“We lived on Train Road, a very important lawyers’ street. There was no tension. There was a lot of unity between the Hindus and the Muslims. Just like one family.”

“When partition came, so did the hassle. There was a Muslim neighborhood next to us and at night the tensions started. We just couldn’t sleep. We were all terrified. For the whole of the night, the mobs would shout ‘Allahu Akbar’ (God is great).”

Suneja’s father decided it wasn’t safe for the women to remain in Lahore and arranged for them to live with relatives in Delhi.

“We arrived at the station in June of July. During those times, your names were listed on the outside of the train compartment. Throughout the train, the doors were being banged from every side and they were chanting ‘Allahu Akbar.’ We didn’t open our doors, we only heard. If we had opened the doors, we would’ve been finished.”

Carriages with Hindu passengers were targeted in the violence.

“People were shouting ‘Open the door!’ Some people were killed in the third compartment. At one station, I remember a loud chanting of ‘Jai Hind’ (Victory to India). We’d reached India. Earlier you could only hear ‘Allahu Akbar’ or ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ (Long Live Pakistan). After 12 hours, we understood that we were safe and that we were in India.”

Suneja’s older brother K.K. Kapur worked in the film industry. Through colleagues in Mumbai, who were Muslim, he was able to exchange his office in Lahore for three rooms in Delhi.

The family may have had a roof over their head but the transition was still tough.

“We didn’t know what to do. We sat on the ground with our luggage but no money, nothing. Such a drastic change was brought to our lives. Terrible moments. We had no utensils to serve so my brother got leaves and we ate on those. People just ran for their lives, leaving all of their luxuries. The only thing mattered was to save their lives.”

The rest of Suneja’s family arrived in Delhi just before August 15 and the family set out to rebuild their lives.

“When my father left Lahore, he heard that our house was going to be attacked, so he called one of his Muslim lawyer friends to occupy our house. The man was very nice, after a few months, he sent our belongings to us. The main thing our father’s library of legal books. Without that he couldn’t have worked.”

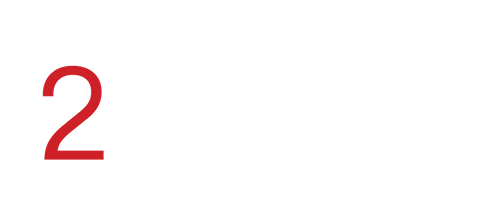

Masroor Ahmed Khan

Omar Khan/CNN

Masroor Ahmed Khan

“We decided to stay back. This is where we were born, where we have lived, where our ancestors are buried.”

Born in 1945, Khan is the descendent of Ajmal Khan, an Indian freedom fighter. He was also a doctor, known as a “hakim,” who practiced Unani, an ancient form of Islamic medicine.

“We have a history of hakims since the time of the Mughal King Akbar. Until my father, it was an unbreakable chain of hakims.”

The hakims came to India from Egypt during the reign of Babur, who founded the Mughal dynasty in 1526. His empire went on to rule for 300 years.

Sitting in the living room of Sharif Manzil, the family mansion that was built in 1740, Khan charts the legacy of his family tree and its subsequent downfall following the creation of India and Pakistan.

Before partition, Sharif Manzil was like a public hospital. It was run by the family and for the good of the public. In the morning, it was crowded by patients from all over India and it worked on a first come first serve basis. No matter who you were, be it a nobleman or a rickshaw puller, Hindus or Muslims. Whoever wanted consultation was treated equally.”

The hakims never charged for their services. Their philanthropy was supported by royal patronage.

For decades, the family’s name continued to prosper and garner the respect of their community.

“Then 1947 happened. From being the richest, we became the poorest because all the property we had was confiscated as evacuee property. People started migrating to Pakistan and the main income from the practice shrunk. In fact, the legacy of Muslims was targeted because Urdu became the official language of Pakistan and India had to oppose it.”

Most of Khan’s family also moved to Pakistan.

“We decided to stay back. This is where we were born, where we have lived, where our ancestors are buried, this is our motherland. Muslims are one of the most fervent believers that this is our motherland. No one has the power to show us. People say go back to Pakistan but we were born here, this is our country. We could’ve gone to Pakistan, we were given an option but we decided to stay back.”

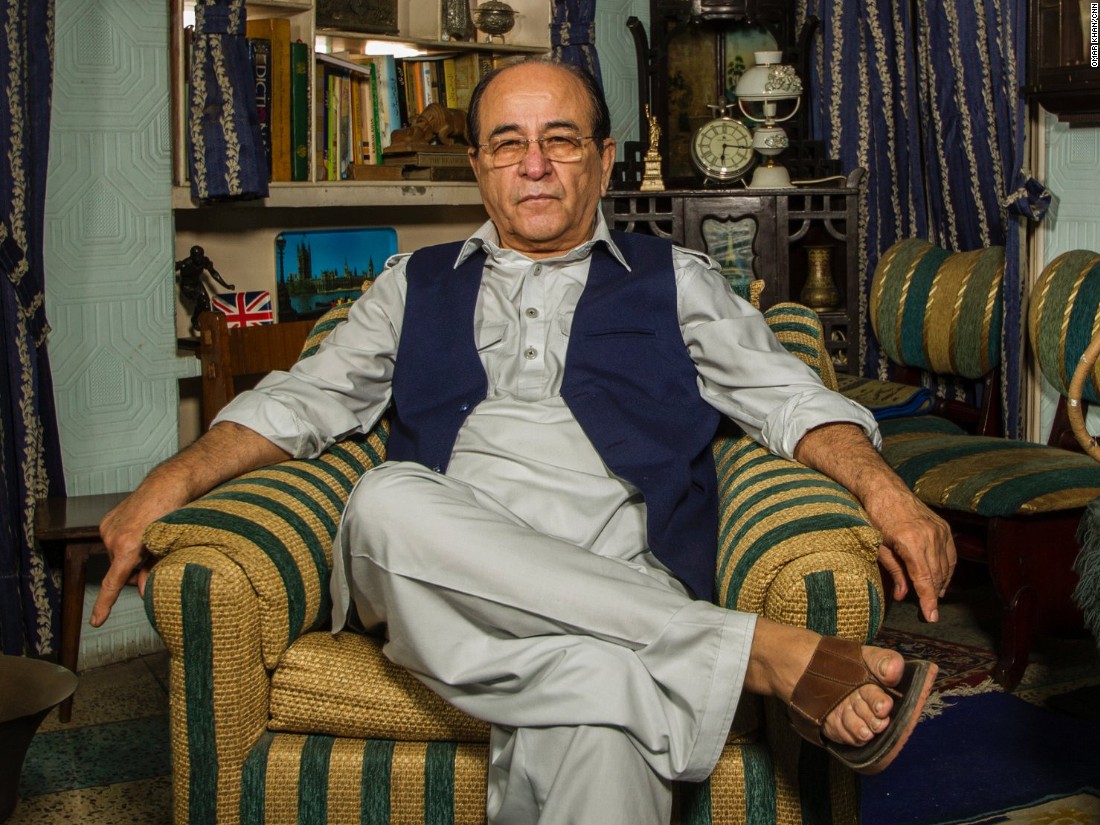

Santosh Kumar Sharma

Omar Khan/CNN

Santosh Kumar Sharma

“There were riots all around. I witnessed everything.”

Sharma was born in 1929 in Gujarat. He grew up in Sialkot district, which is now in Pakistan.

After finishing school, he joined the army as a clerk during the Second World War.

Once the war was over, he got a job as a customs officer, a job that brought him respect and posted him in various cities and towns.

Sharma was 17 during the partition of the Indian subcontinent and lived in Pakistan’s Narowal district at the time. He remembers a great deal of violence in the months leading to independence.

“There were agitations from the Muslim community. The majority of Muslims there wanted Pakistan. There were riots all around. I witnessed everything. In those days, I used to go the daily meetings of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (Hindu youth organization) and one morning, a Muslim friend of mine came to me and said, ‘Santosh, it is not proper for you to stay here. You are living here alone with no family members, you are a guest of ours so you better go to your own native place because they are naming you as an active worker of the RSS.’”

The journey to India was long and arduous. After a failed attempt to go to Jammu and Kashmir, still an independent state, Sharma reached a refugee camp in Amritsar.

It was in Amritsar where he was reunited with his uncle.

“He told me they had had no communication with my parents and that me being there was of no use. Since all my relations were in Pakistan, I had opted to serve in Pakistan but our headquarters were in Delhi. So, I thought I should go to Delhi. There was a goods train going from Amritsar to Delhi. I jumped on and travelled on the rooftop to Delhi. When I reached (the city), I went to the office and they found my old records. At that time, I still wanted to work in Pakistan but when I found out I would not be able to reach there, they allowed me to work in Delhi.”

The two years that followed would see Sharma continue to search for his family while being posted to various other towns. In 1949, in Palampur in the state of Himachal Pradesh, he finally learned that his family had moved to Ludhiana in India’s Punjab state and were safe.

“I told my uncle they had migrated to Ludhiana so I went there where I finally met my mother and one brother.”

Sharma’s tale of searching for family members is not unusual. Families were split apart during the mass upheaval often learning of their relatives’ whereabouts years later. Others never found out.

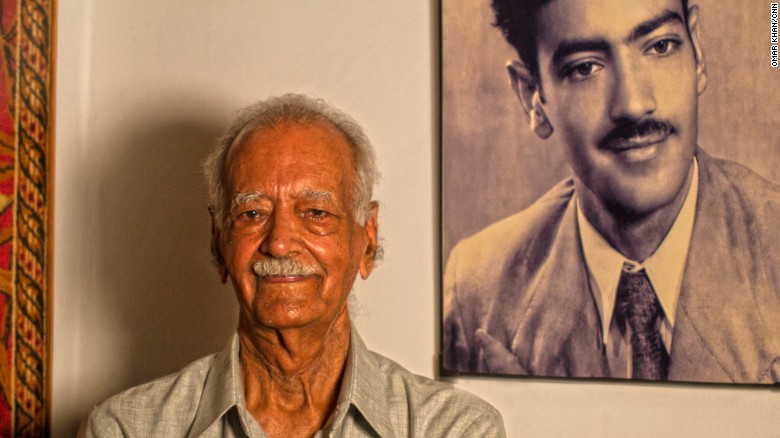

Aanchal Malhotra

Omar Khan/CNN

Aanchal Malhotra

“...we will go so further into the future and the past will recede so much that the divide between the two will become enormous.”

Writer and oral historian Malhotra’s forthcoming book looks at the stories behind the objects that people brought with them as they crossed between India and Pakistan during the partition.

Some are ordinary, others are items of value, sentiment and promises of new futures.

The idea for the book came after a photographer friend asked for help on a piece on old houses in New Delhi.

“While they were talking, my grandfather’s eldest brother came back with all these old things and said: “You know if you must talk about the past, you must talk about it in its entirety. And these things here are older than the family members that live in this house.”

Out of those things, two happened to be from Lahore that his parents had brought just before partition. One was a ghada, which is a vessel in which his mother churned lassi (yoghurt drink) and one was a guz, which is a yardstick used to measure fabric.

He said those things were the oldest things that he owned and while he was talking about them, I had never seen a visceral, tactile transportation of somebody into the past because of an object. I didn’t know objects had the ability to do that.”

This “surreal” experience sparked a flurry of questions within Malhotra’s mind.

“What about things that had come during partition? What did they bring? Because they always said we didn’t bring anything. Why had I never read anything about it? I started doing research at home and it turns out my family, both my grandparents brought tons of stuff through incredible circumstances. There were a variety of things depending on the circumstance that you migrated and somethings were small enough to hide in your clothes, others were brought if you had time.”

Like others documenting partition, Malhotra is aware that those who witnessed this turbulent period of history may soon not be around to share their experiences.

“What is going to happen very soon is that we will go so further into the future and the past will recede so much that the divide between the two will become enormous, without any knowledge to fill it. It’s weird for me to know that something I’m reading in a book is something that someone I know lived. That’s very strange for me and makes it that much important to know orally what we can of it.”

Malhotra began working on her book in 2013. In that time, she has spoken to 50 people in both India and Pakistan.

“If you knew that partition was going to happen, and you had the means, then you sent things in a goods train. If you knew that partition was going to happen but didn’t have the means, you took things that were of value that you could sell, that you could restart your life with. There were some obvious things that people brought like valuables, jewelry, things they could sell. Many people carried, that I was surprised by, utensils. If you didn’t know that partition was going to happen, what do you take then? You fumble, you stumble, you take things literally in front of your eyes.”

Malhotra does admit that the process has been demanding though crucial for future generations.

“I have this sense that I have to take things that are given to me. So, when we are in conversation, it really feels like this person is like, ‘Let me just reach inside and get something very precious and okay, now it belongs to you.’ So, when somebody does that, you must take care of it. You must do justice to this memory and you must take care of it.”

“What I’m trying to do is I’m trying to eradicate any violence around partition. There is a lot of hush hush around it that doesn’t need to be there. I hope that at some point in the future, we will be educated carriers of our history but for that conversation is imperative.”

‘Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory’ is published by HarperCollins. Find out more about Malhotra’s work and the objects documented.

Mallika Ahluwalia

Omar Khan/CNN

Mallika Ahluwalia

“...because the generation is quite old they want, before they move on, for their stories to be heard.”

Ahluwalia heads the Partition Museum, the world’s first museum devoted to the brutal 1947 split of the Indian Empire into two countries.

“The realization hit us that we’re approaching 70 years and the generation that experienced partition is leaving us. How is it that we don’t have a museum of memorial to partition? This remains the largest migration in human history. It was an event that impacted between 12 to 18 million people, and yet there is no museum or memorial.”

A small section of the museum opened to the public in October 2016 with around 40,000 people visiting since then. The full launch is slated for August 17 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Indian independence.

The museum is in Amritsar, in the Indian state of Punjab near the Pakistani border, which Ahluwalia says was a conscious decision.

“It felt important to us that the first museum on partition in the world should be in Punjab. And within that, Amritsar, because it witnessed so much. Before partition, nearly half of its population was Muslim. By the end, it had dropped to less than 1%. Beyond that, it’s a border city, a lot of refugees were transiting from one side to the other so in addition to its own population change, it was also this transit point.”

This is a museum for the people and by the people with all funding and artifacts donated by the public.

“Our idea was that this is not a museum on the macro-events of partition, it’s not trying to assign blame, it’s trying to say let’s acknowledge and remember that millions of people suffered at that time, so to make it a people's museum, to tell their stories, to make sure that their voices and experiences are memorialized through using their oral histories, their objects, their photographs, their letters.”

The memories and eyewitness accounts that fill the Partition Museum range from harrowing to humbling.

“There’s this beautiful love story of the phulkari (embroidered) coat and the briefcase. She was engaged to be married but in the chaos of partition she lost contact with her fiancé’s family.

When the violence started, a lot of families decided to send the children ahead to safety. Somehow, she managed to make her way to a refugee camp in Amritsar, and she had decided to bring with her this phulkari jacket. If you remember, it is the middle of the summer, it’s the monsoon, it’s a highly impractical thing to be carrying with you but it was just her favorite thing.

In the refugee camp, she ran into her fiancé in the line for food and they got married the following year. He was carrying a briefcase with him, in which he had his property papers and school certificates, and so we’ve placed those objects in the museum as a kind of a symbol of the life that they had lost and found together.”

Through sourcing stories for the museum, Ahluwalia has found most people want to share their experiences.

“For a long time, there was a silence around partition. In the immediate aftermath, it was so raw and overpowering that people didn’t want to talk about it, and there was also a sense that people needed to pick up their lives and restart. There was no space to breathe or pause and remember. But now, I think that because the generation is quite old they want, before they move on, for their stories to be heard.”

Ahluwalia hopes the Partition Museum will continue to educate visitors, some of whom have been impacted by the event on a personal level.

Their suggestion to the Punjab government to memorialize August 17th, also the day that the borders between India and Pakistan were officially announced, as Partition Remembrance Day has also been accepted.

“The same way that there is a day to remember the victims of the Holocaust or the people who were in World War II. We thought it was important that this event that impacted so many have a day. This year will be the first Partition Remembrance Day and it will continue annually after that. Hopefully, it will continue to be something that will be adopted globally.”

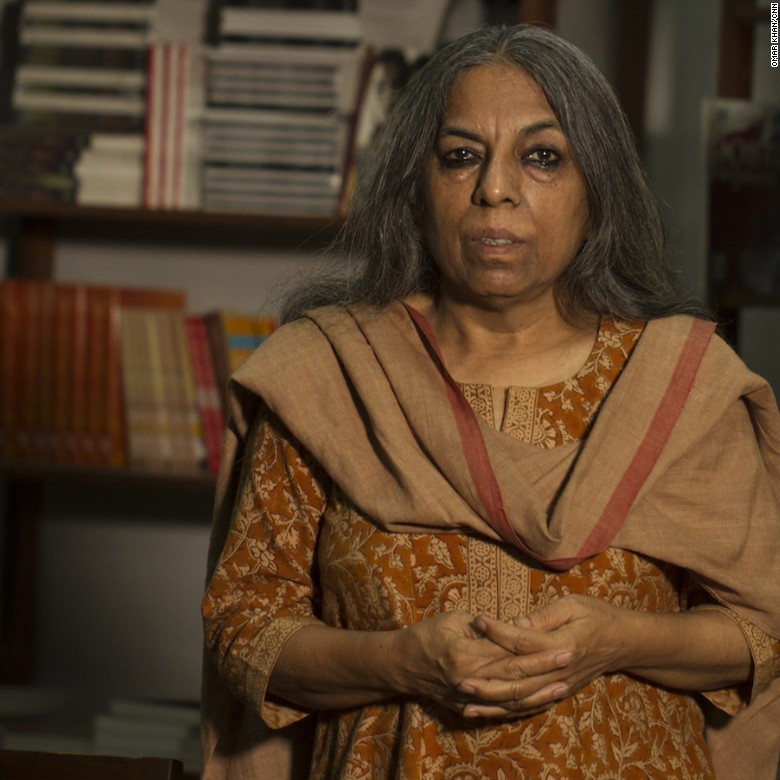

Urvashi Butalia

Omar Khan/CNN

Urvashi Butalia

“There was a long silence after partition, for many reasons.”

Writer and publisher Butalia’s book ‘The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India’ is based on the experiences of those who lived through the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent.

The book, considered a seminal piece of work on the period, came about by chance when she began to help friends research a film on partition.

“I traveled a bit around Punjab and Delhi and talked to some people for them, and suddenly started to hear and listen to their stories. Roughly around the same time, 1984 (anti-Sikh riots) happened, Indira Gandhi got assassinated. And suddenly the face of Delhi changed.

You could see violence everywhere. I started to work with a citizens group set up to help the victims of the violence. I kept hearing from them, ‘This is like partition. We had never thought that this would happen to us in our own country, we never thought that we would see this violence.’

Suddenly it hit me that if a few days of violence could shake people so deeply, what must have happened at the time of partition? And why was it that we, my generation of people, who were the first generation after partition, had never paid it any attention, never thought that it needed to be looked at. I began to feel that it was something that I should look at.”

Butalia’s first step was to go to Pakistan and meet relatives who chose to stay rather than journey across into India.

“My mother’s brother stayed behind in Lahore and had refused to come to what became India. He kept the family home, he kept my grandmother back and made her convert. So, my mother and her siblings never saw their mother or brother again after partition. But they always carried this memory of him, this kind of resentment.

They felt he had been very manipulative and the fact that he had kept the family home meant that they didn’t get any compensation on this side. So, all of them had to start afresh and there were a lot of complicated feelings. I pitched up at his house and told him ‘I’m your sister’s daughter from across the border.’ And then we started talking and it became clear to me how complicated the whole history was. Even in a family that had not faced any physical violence, how deep the cleavages were, how profound the hurt was.”

Published in 1998, Butalia collected stories and interviews for nearly a decade for the book.

“There was a long silence after partition, for many reasons. Part of it was that people did not want to talk because the focus was on remaking lives. Part of it was that people did not want to talk because people did not want to listen. For example, when I was interviewing one of the women in my book, her sister sat in on the interview. And that was the first time she was listening to her sister’s story and it was a story of so much trauma and hardship.”

Butalia adds that for many women who crossed between the two newly created nations, there were other reasons behind the silence.

“How could they speak? Many of them lived through violence, through rape and abduction. It’s very difficult to speak about that in times of peace. You speak about that moment and families who lost women to sexual violence just pretended as if these women didn’t exist, that they had disappeared into some dark hole. They never acknowledged the existence of those women. So, if you don’t have an existence, if no one is there to listen to you, if the subjects won’t speak about it, how do you speak about it?”

As a writer and publisher who dedicates much of her work to the cause of feminism, Butalia was especially keen to learn about the experiences of women who often find themselves at the fringes of society.

“There were a lot of families that killed their own women. There was a real fear in Hindu and Sikh families that the women would be abducted, kidnapped, raped, impregnated and there’s this value that Hinduism lays in purity and in pollution.

So, for a woman to be sexually assaulted by a man of another religion and to become pregnant, there could be no further insult in the religion. Islam is much more practical about that. Purity and pollution aren’t such major factors. How do you speak about this? Who will speak about it? The whole narrative is one of honor and honor killings, when it’s actually murder. So, the reason for not speaking is also that they were complicit in the violence.”

Nearly 20 years after her book was published, the stories shared with Butalia remain with her.

“The level of violence that people can sink to really made me think how much violence lies inside us. And what can make somebody turn someone who was a neighbor or a friend to someone who can kill with such cruelty. But I was also surprised by the fact that people who had lived through such terrible violence, who had been at the receiving end of it, came out with so much compassion and understanding. I was constantly surprised by that humanity.”

She also believes the legacy of partition is an intrinsic part of the tumultuous relations between India and Pakistan that followed.

“Partition is there in everything. The most obvious thing is the impossibility of crossing borders. You see it in the Indus Water Treaty, you see it in the fact that they are not able to trade with each other openly. You see it in the hatred of the Muslim in India and it’s there in every bit of violence that takes place between communities.

I don’t think traumatic histories disappear with such ease. Countries need a deep maturity to be able to confront them and our two countries don’t have that. This is the dark side of independence and in order to confront it, we will have to allow ourselves to admit that we were sort of complicit. It’s not like, they were the bad guys, we were the good guys.

You can say the Nazis were the aggressors, the Jews were the victims and the citizens were complicit in allowing this to happen. But here, the Hindus killed and maimed and raped as much as the Muslims did, and in that sense we have to look at our past and say how did we get to this point? Where did we go wrong? And there needs to be a genuine will to move out of that.”