You’ve probably heard of Mahatma Gandhi, the loincloth-clad man who fronted India’s fight for independence from the British. But right beside him and other male leaders, was an army of women whose trials and tribulations were every bit as compelling.

Their fight began as early as the late 19th century, when some took to the battlefields and one queen even led an armed rebellion against the British.

They also fought a domestic battle against oppressive traditions, such as sati (the burning of a wife on her husband’s funeral pyre) and child marriage. Sadly, the latter still exists today.

These women did not have it easy – they were some of the worst victims of the traumatic events that took place in south Asia in the mid-20th century. It’s reported that 75,000 women were abducted and raped during partition, the division that separated Pakistan from India, which took place at the same time as independence in August 1947.

From setting up a secret radio station to running for president when it was perceived to be a man’s role, these are some of the empowering stories that are often left untold.

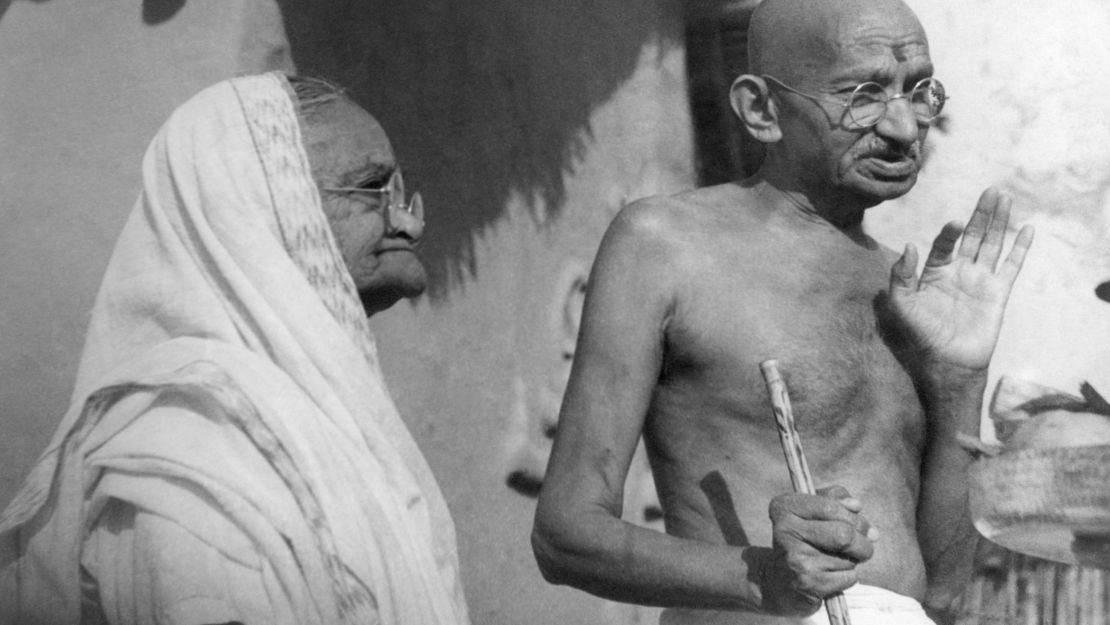

Kasturba Gandhi (1869 - 1944)

“I learned the lesson of non-violence from my wife,” Mohandas Gandhi, better known as Mahatma Gandhi, once said. Kasturba Gandhi’s passive disobedience of her husband is said to have influenced the father of the nation’s renowned peaceful movement.

Married when they were both just 13 years old and schooled by her husband, she became a social activist in her thirties in South Africa, and was imprisoned there for three months for protesting against the treatment of Indian immigrants in the country.

Although she was plagued with health problems, she continued her activism work when she returned to India, where she was also arrested and jailed a few more times. In 1942, she was imprisoned along with her freedom-fighting husband and other pro-independence leaders for taking part in Gandhi’s Quit India movement – an effort to encourage the British to allow India to rule itself. Her health deteriorated and she died in prison in 1944.

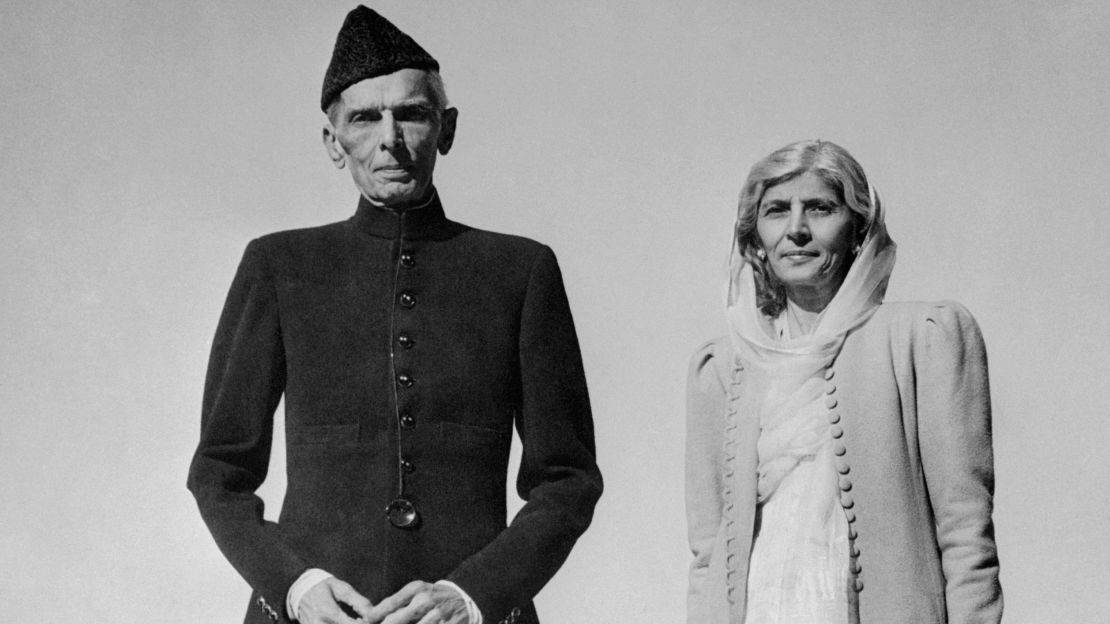

Fatima Jinnah (1893 - 1967)

Standing firmly alongside Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, was his sister. Fatima Jinnah is fondly remembered as Madar-i Millat, the mother of the nation.

Taking an early interest in politics and playing an active part in women’s rights, she represented an advance in the status of women even before Pakistan was born, wrote author M. Reza Pirbhai. “She was English educated, a professional dentist and an unveiled social worker even before the word Pakistan was coined in the 1930s.”

In 1964-5, when she was in her seventies, she even ran for president – a role widely viewed as unacceptable for women. Although she lost, her bold move was praised by Pakistanis, wrote Pirbhai.

After India and Pakistan’s independence, Jinnah also took part in refugee relief work and formed the Women’s Relief Committee during the transfer of power, which evolved into the All Pakistan Women’s Association.

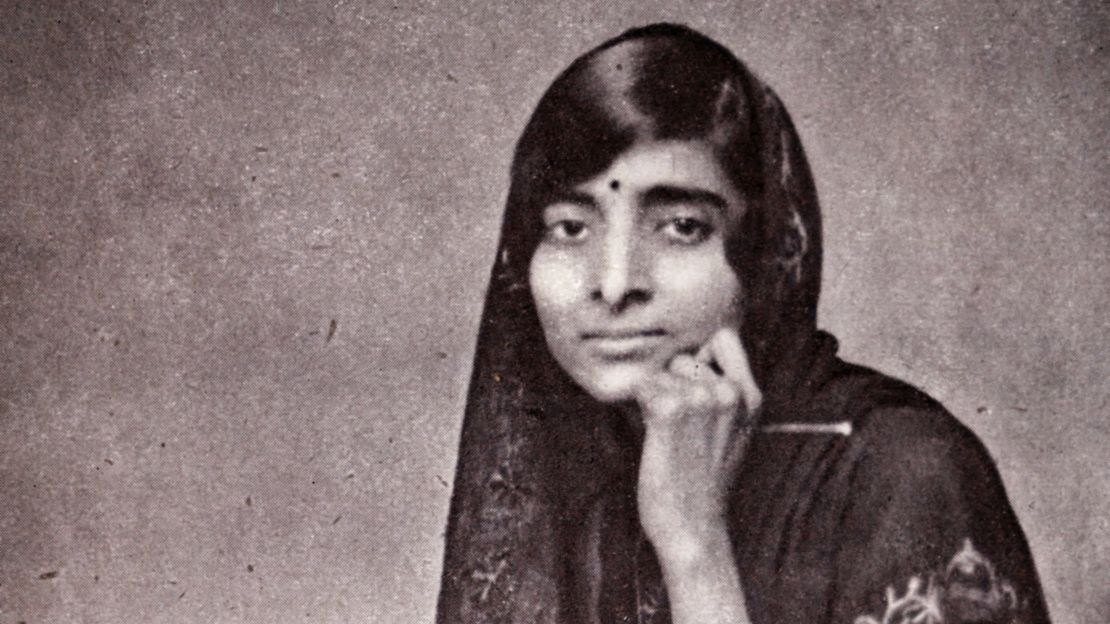

Kamala Nehru (1899 - 1936)

Speaking to a gathering of women in Allahabad, a city in the north of India, the wife of the country’s first prime minister said: “Ours is a peaceful fight. It does not need the use of swords or lathis (sticks).” She was encouraging them to join Gandhi’s Civil Disobedience Movement – passively disobeying British rules and law.

Nehru married Jawaharlal Nehru on February 8, 1916 at the age of 17, when he was 26. She supported him in his fight for independence and played a prominent part in political processions, setting up a dispensary in her house for wounded freedom fighters and advocating women’s education.

She was imprisoned on January 1, 1931 for her role in the Civil Disobedience Movement. As she was arrested, she told a reporter: “…I hope the people will keep the flag flying.”

Nehru was mother to Indira Gandhi, who became the country’s first female prime minister in 1966. She passed away from tuberculosis in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1936.

Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan (1905 - 1990)

Born into an upper caste Hindu family, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan converted to Islam when she got married to Muslim lawyer Liaquat Ali Khan, who later became the first prime minister of Pakistan.

Khan and her husband met Muhammad Ali Jinnah, chief of the Muslim League, while on honeymoon in London. They convinced him to return to India and resume leadership of the movement and banded together in their fight to liberate India and form Pakistan.

Khan helped the refugees who fled India during partition and also organized the All Pakistan Women’s Association in 1949, two years after the creation of her country.

Noticing that there were not many nurses in Karachi, a coastal city in the south, Khan requested the army to train women to give injections and first aid. This resulted in the para-military forces for women. Nursing also became a career path for many girls.

She continued her mission, even after her husband was assassinated in 1951, and became the first Muslim woman delegate to the United Nations in 1952.

Usha Mehta (1920 - 2000)

Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi as a child, Usha Mehta ran a secret radio station with her friends during Gandhi’s Quit India movement in August 1942, despite disapproval from her father, who worked as a judge under British rule.

“When the press is gagged and all news banned, a transmitter certainly helps a good deal in furnishing the public with the facts of the happenings and in spreading the message of rebellion in the remotest corners of the country,” she said in an interview in 1969.

But in November of the same year, Mehta and her friends were arrested – an event she described as her “finest moment.”

Her staunch refusal to respond to months of police interrogation in 1942 led to her being locked up for four years in Yerwada jail in the west of India, where Gandhi was jailed twice, alongside 250 other female political prisoners.

After being released, she said: “I came back from jail a happy and, to an extent, a proud person, because I had the satisfaction of carrying out Bapu’s (Gandhi) message ‘do or die’ and of having contributed my humble might to the cause of freedom.”