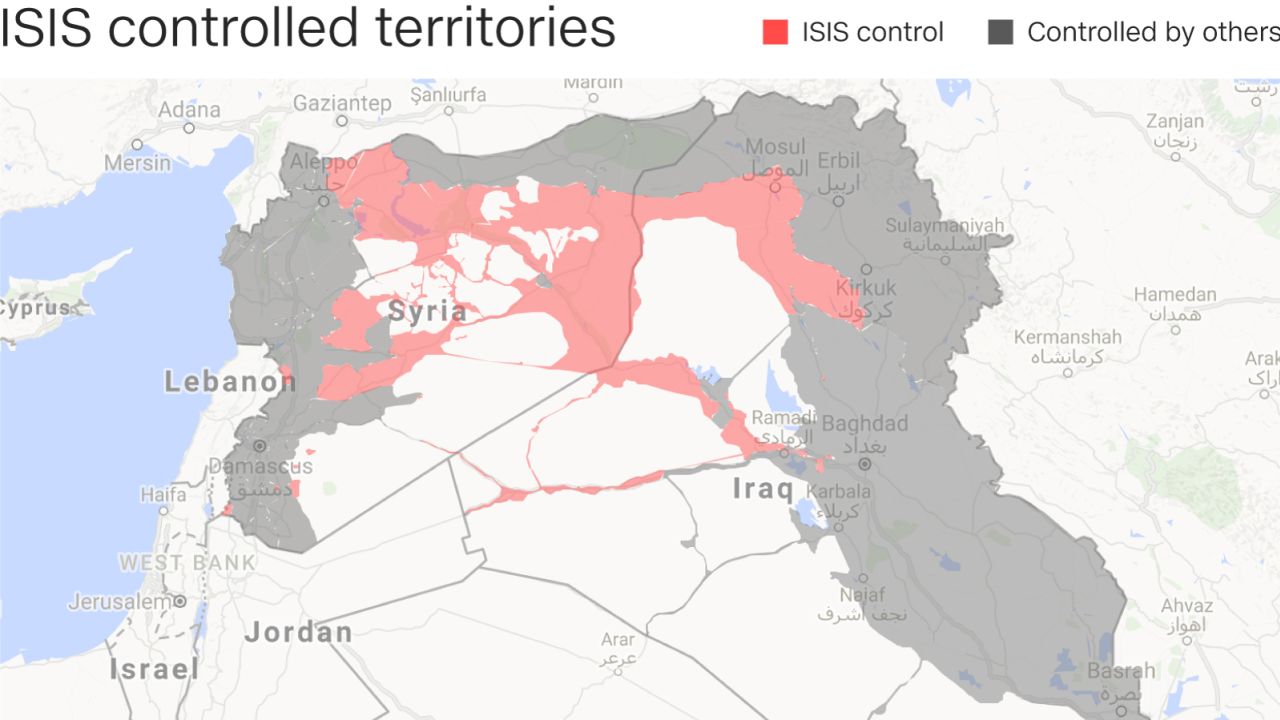

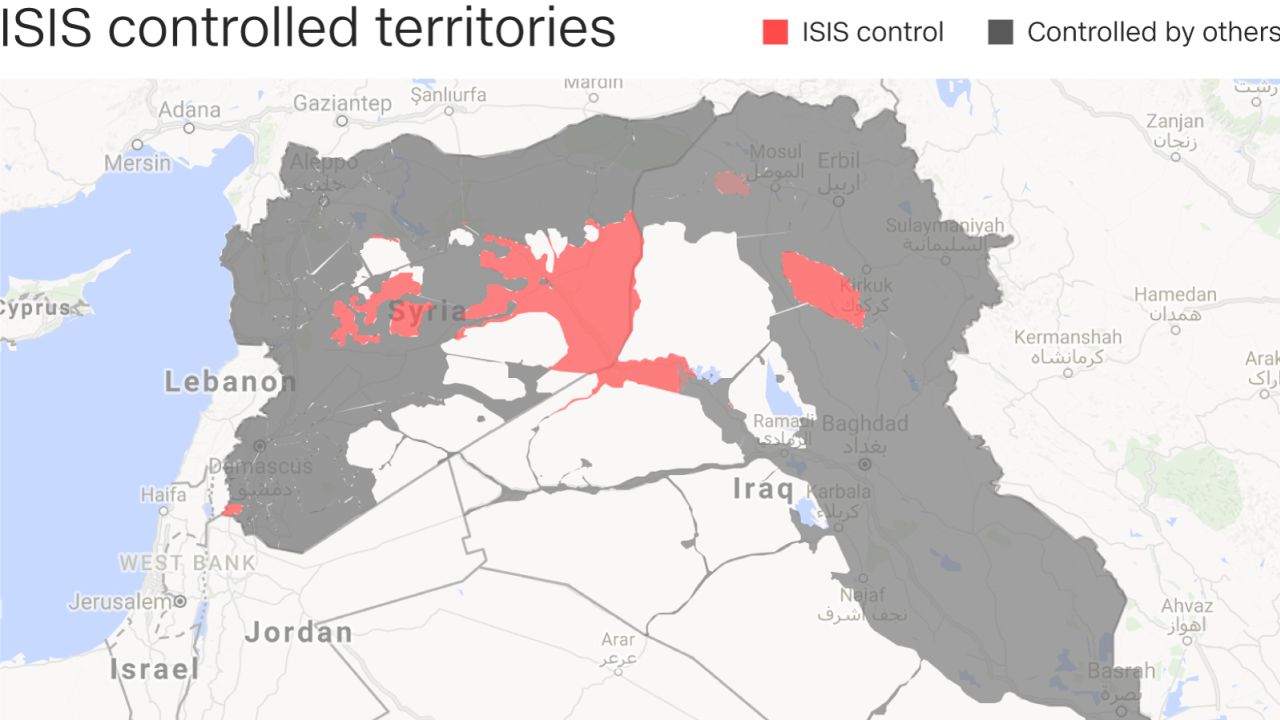

Syrian troops broke ISIS’ three-year siege of Deir Ezzor – a strategic city in the eastern part of the country – on Tuesday, marking the latest in a series of setbacks for the terror group.

In recent weeks, ISIS has been driven from one refuge to the next as its territory in Iraq and Syria continues to shrivel.

In late August, Iraqi security forces surrounded the town of Tal Afar, some 80 kilometers (50 miles) west of Mosul. Despite official predictions of a long, difficult slog, the town was cleared of ISIS fighters within a week – with militants literally dragged from sewers.

In northern Syria, US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) have pushed forward into the Old City of Raqqa. The SDF now controls two-thirds of ISIS’ de-facto capital, which, not so long ago, served as the group’s administrative headquarters and ground-zero for plotting overseas attacks.

And this week, the Syrian army reached the western front of Deir Ezzor – ending ISIS’ siege of the 137th Brigade Base, a garrison that has long relied on airdrops to survive. Ceasefires arranged elsewhere in Syria, under Russian auspices, freed up the Syrian army to advance east – allowing them to race across 200 kilometers of desert to Deir Ezzor in just a few weeks.

The swift breakthrough by Assad’s forces there has surprised many observers.

Deir Ezzor is arguably more important than either Tal Afar or Raqqa. It sits at the heart of Syria’s oilfields, once an essential source of income to ISIS, and is Syria’s main gateway to Iraq. It’s also one of the most crucial in a string of towns along the Euphrates River, where ISIS is expected to make its last stand.

ISIS still holds much of the city, thought to be home to a remaining 90,000 civilians (though many more have fled), and controls territory to the south of the Euphrates. But it is quickly running out of fighters, supplies and escape routes.

That’s in no small measure due to Russian airpower. Deployed at first against other rebel groups in the northwest of Syria, it has more recently been trained on ISIS. Nearly three weeks ago, the Russian Defense Ministry released aerial footage purportedly showing the destruction of an ISIS convoy near the city, destroying heavy weapons and killing more than 200 militants.

This week Russian warships in the Mediterranean fired cruise missiles at ISIS positions and weapons depots.

But if the caliphate is on the verge of extinction, ISIS is not. And its many enemies may soon turn their guns on each other.

Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulated Syrian forces on their advance on Deir Ezzor, but said on Tuesday: “Can we say that we have done away with ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra [the former al Qaeda affiliate] and other terrorist groups forever? It is probably too early to say so, but it is obvious that the situation is changing drastically in Syria.”

ISIS morale crumbles

ISIS is certainly beginning to suffer a loss of morale after a series of defeats.

US Brigadier General Andrew Croft, chief of coalition air operations over Iraq, says ISIS’ leadership is “more fractured, less robust, and sort of flimsy … it is sporadic.”

Last week, some 300 of its fighters in western Syria – near the Lebanese border – cut a deal with their arch-enemy Hezbollah (the Lebanese Shia militia) and with the Syrian regime to be allowed to leave, unarmed, for ISIS sanctuaries in eastern Syria. A week later their buses remain stranded in the desert, and their destination is under attack.

There are also reports of dissent in ISIS’ ranks. According to some accounts, this has led to armed clashes, with the group’s “ultra” hardliners accusing ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi of being too lax in targeting “apostates.” It speaks volumes about ISIS that amid disastrous battlefield setbacks it can still be consumed by an arcane ideological dispute.

Sources in Syria say that the remaining leadership, plus ISIS communications infrastructure and any chemical weapons capability, began moving to the Euphrates River valley earlier this year – specifically to an area linking Mayadin and Abu Kamal in Syria with Qa’im across the border in Iraq.

Both US and Russian airpower have been active in this area in the last few months. The US says it has killed several important ISIS leaders in and around Mayadin since April.

But the battlefield in eastern Syria has become very crowded, complicating Syria’s future even as the threat from ISIS recedes. Concentrated in an area scarcely 100-kilometers wide are the Syrian army, its allies, including Hezbollah and Iranian Shia militia, as well as Kurdish and Arab tribal groups. Just across the border is the Iraqi army and more (Iraqi) Shia militia, supplied by Iran. In the skies above are US, Russian, Syrian and Iraqi jets.

ISIS mutates

Amid immense pressure, ISIS is mutating rather than dying.

The group is returning to its roots as an insurgency – grounded in expertise, experience and cash. ISIS rose out of an underground movement, organized in cells across Sunni parts of Iraq, and will try to revert to life as such.

In the view of the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington-based think tank that has closely followed the conflicts in Iraq and Syria, “Russia’s punitive strikes against vulnerable Sunni populations will exacerbate local grievances, increase sectarian tension, and pave the way for the resurgence of ISIS, al Qaeda, and other jihadist groups in areas recently seized from ISIS …”

ISIS thinks in millennial terms. Even if the physical caliphate evaporates, its spirit will persist. Suffering and defeat is part of a centuries-old campaign.

There is a saying attributed to the Prophet that is often quoted by ISIS ideologues and followers: “A victorious band of warriors from my followers shall continue to fight for the truth. Despite being deserted and abandoned, they will be at the gates of Jerusalem and its surroundings, they will be at the gates of Damascus and its surroundings.”

It is this millennial belief that sustains what remains of ISIS. Its organizational talent allows it to probe for weaknesses among its enemies.

ISIS has cultivated deep roots in Sunni parts of Iraq (less so in Syria where many jihadists regard it as an interloper). Over the past decade, it has developed networks skilled at raising money and obtaining weapons across a wide swathe of Iraq – from Diyala in the east to the Jordanian border.

It has shown that it can penetrate security in Baghdad to detonate devastating car bombs. In some ways, it is returning to what it does best – agile attacks, mobility and surprise.

ISIS may yet benefit from the mutual distrust among its enemies.

Deir Ezzor is an important link in Iran’s dream of connecting Tehran, Baghdad and Beirut in a land corridor for regional (for which read Shia) influence.

The US has supported moderate Syrian rebels along the Syria-Iraq border in an effort to stymie Tehran’s ambition. Kurds have carved out a wide slice of northern Syria as their own. Some Arab tribes in the region support the Assad regime; others oppose it.

Right now, the regime and its Iranian and Russian backers are in the ascendant, but it’s a landscape ripe for further bloodletting.

From Raqqa to Mosul, the ISIS flag is being torn down. But its ability to inflict terror, to take advantage of ungoverned spaces and exploit sectarian hatred is far from extinguished.

Graphics by CNN’s Henrik Pettersson.