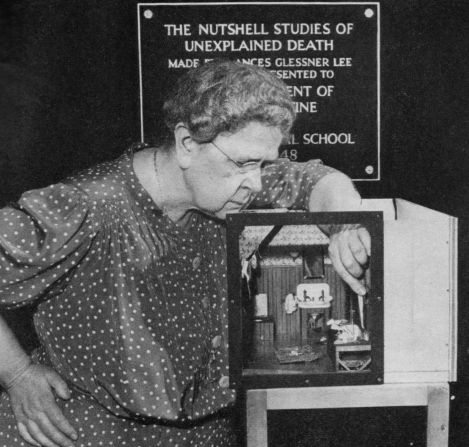

The patron saint of forensic science is not a cast member of “CSI” but Frances Glessner Lee, a Chicago heiress, who, in the 1940s, upended homicide investigation with a revolutionary tool: dollhouses.

“She probably would object to them being called dollhouses, even though that’s where they came from, because she was so desperate to have them considered to be real scientific objects, and a dollhouse was just a children’s toy,” said Nora Atkinson, curator of “Murder is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” an effort to bring Lee’s work into the spotlight at Washington’s Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

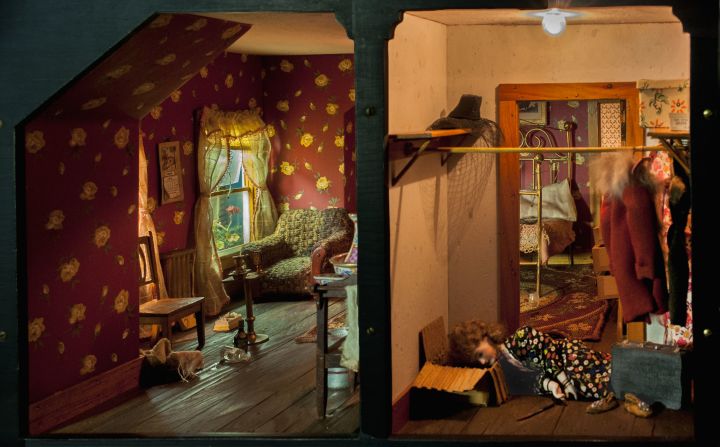

Equipped with flashlights and magnifying glasses, visitors are tasked with inspecting miniature crime scenes – the titular “nutshells” – Lee built to help detectives practice the art of observation. With blood-spattered walls, burned-down wood cabins and decomposing skin, the dioramas are beautiful, small-scale messes.

Breaking conventions

Frances Glessner Lee was born to a wealthy family in 1878. As the daughter of the co-founder of the International Harvester Company, her life was meant to be an unperturbed existence of needlework, embroidery, interior design and marriage.

But her heart was set on the intricacies of scientific homicide investigation, which was, at that point, still in its infancy. Lee’s offbeat leanings towards medical reports were spurred by Sherlock Holmes stories, and the case of H.H. Holmes, one of America’s first serial killers, who lured his victims into a labyrinthine building, later nicknamed the “murder castle.”

Unsurprisingly for the time, “her father felt that … being involved with the police and medical investigations was a very sordid affair. He wanted no one in the Glessner family to be involved in it, so her whole life was filled with this unrequited desire to be able to be part of that world,” Atkinson said.

But Lee was not happy in the role she had been cast. In her 70s, she would bemoan being categorized as a “rich woman who didn’t have enough to do.” Her marriage to a lawyer ended in 1914, after only 16 years.

It was only after her brother’s death in the 1929 that she was able to finally pursue her career. Already in her 50s, Lee put conventions to the side and donated part of her fortune to Harvard’s first-ever Department of Legal Medicine that year.

“The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” – named after the saying: “Convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell” – came in the 1940s as an ingenious solution to help train detectives. Indeed, Lee subverted the dollhouse, turning miniature fairy tale abodes into grisly crime scenes, built at a scale of one inch to one foot.

The scenes, based on real crime stories, were built to help students in Harvard’s Department of Legal Medicine learn how to accurately process a crime scene, and they are still used in training.

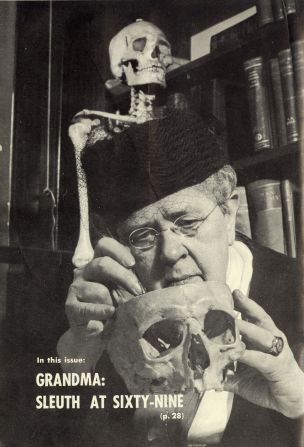

Detectives carefully analyze the three-dimensional murder scenes, develop a scientific methodology, and decide which objects to study in the lab. Far from a simple whodunit, Atkinson assures the nutshells are hard to crack.

Murder, she built

Artistic details are dotted throughout the 20 murder models – 18 of which have survived – even though Lee didn’t consider herself an artist. With their intricate detailing, pain-staking painting, and working doors and lights, the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Deaths” are as much a manifesto on useful art as they are an investigatory aid.

(Fittingly, transgressive filmmaker John Waters is a fan. “When I saw these miniature crime scenes,” he said in an e-mail to The New York Times, “I felt breathless over the devotion that went into their creation. Even the most depraved Barbie Doll collector couldn’t top this.”)

“There’s been such a divide in this country between arts and science in schools,” Atkinson said. “We’re talking about a woman who was thinking about these things … holistically, and realizing the value that arts and crafts can bring to a scientific field.

“(Lee) was using the crafts that were available to her to be able to break into a man’s world. She was actually able to cross a boundary and contribute something that the men in that field never would have thought of, through something that was traditionally considered women’s work.”

It’s hard to look at these miniature murder scenes and not become a six-inch detective trying to unravel the situations. But the silver bullet is kept under wraps so that other detectives in-the-making can try their hands at it.

“Murder is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” is on display at Washington’s Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum from October 20 to January 28, 2018.